In last month’s Short Story, we feasted on dazzling jewelry designs from Cooper Hewitt’s collection. This month, Sarah Coffin, curator and head of product design and decorative arts, introduces us to Mr. and Mrs. John Innes Kane, donors of some of Cooper Hewitt’s most important decorative art pieces.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

High Style from New York’s high society

Mr. and Mrs. John Innes Kane, a couple who were strong supporters of Cooper Hewitt’s collection, were both born into the same small world of social connections, wealth, and privilege that the museum’s founders, the Hewitt Sisters, inhabited. John (1850–1913) was the great-grandson of fur trader and real estate magnate John Jacob Astor; John’s wife, the former Annie Cottenet Schermerhorn (1858–1926), hailed from a family with Dutch origins dating back to the time of New Amsterdam, which later became New York. Her longer genealogy in the forefront of New York further improved his social status given that the Kane name, in and of itself, did not have the cachet of his Astor forebears. The name Astor is almost synonymous with wealth and society, partly due to Caroline Schermerhorn Astor (1830–1908)—another Schermerhorn, of a previous generation—who had married an Astor relative of John Kane’s. Caroline, known as Lina and perhaps the grande dame of New York society, codified high society in New York through her list of approximately 400 people she considered worthy of inviting to her annual balls. These socially elite friends were first referred to as the “Fashionable 400” by an Astor cousin-by-marriage, Ward McAllister. The criteria for acceptance included an emphasis on the families who had had a lot of money for a few generations—a difference with the current Forbes 400, whose only criterion is how much money those listed might have at the time of selection. The Fashionable 400 was rumored to be the maximum Lina’s ballroom could hold, but her ballroom capacity was more correctly counted as a mere 273! Caroline was a formidable woman of a generation earlier than Annie, but who, no doubt, had an impact on her.

Despite this association of wealth from generations past with the Astors, both Schermerhorn women had considerable inherited funds of their own and husbands less interested in the social whirl than they. Annie also had wealth not only from her Schermerhorn forebears’ shipping business, but from her Cottenet grandparents, whose import-export business was founded upon their arrival from France in 1822. Such businesses imported a great variety of objects, including, porcelain, other decorative arts, and furniture by Parisian furniture makers to an increasingly cosmopolitan New York. The result was an expansion of the hold on New York of the French Empire style, which was the height of fashion at the very time that the Cottenets came to the city. Charles-Honoré Lannuier and other French-born and trained cabinetmakers came to New York producing high-quality wares like those they made in France, often with imported French mounts; soon they were imitated by local furniture makers. It appears that a group of French-Empire-style furniture, made in New York in the 1820s that Annie Schermerhorn Kane bequeathed to Cooper Hewitt upon her death, came from her family, rather than purchased in her and her husband’s collecting days. It is possible, given that her husband also had New York forebears, that an earlier Federal sideboard made in New York, dating to the 1790s, and British in style, may have descended from his Astor forebears. John Jacob Astor’s wife was Scottish so they might well have furnished their house in more British taste.

Settee (USA), 1815–20; Mahogany, mahogany veneer on cherry, gilding, paint, gilt metal (mounts); upholstery: cotton and horsehair (replaced); H x W x D (approx.): 87 x 234 x 68 cm (34 1/4 in. x 7 ft. 8 1/8 in. x 26 3/4 in.); Gift of Mrs. John Innes Kane, 1920-19-85-a/d

Cellarette (New York, New York, USA), ca. 1825; Mahogany, other wood (inlay), gilt bronze; H x W x D: 67.5 × 63.5 × 45.7 cm (26 9/16 in. × 25 in. × 18 in.); Bequest of Mrs. John Innes Kane, 1926-22-90-a/c

Sideboard (New York, New York, USA), ca. 1800; Mahogany, white pine, tulip, poplar, box (inlay), brass (pulls); Bequest of Mrs. John Innes Kane, 1926-37-244-a/h

Like the Hewitt sisters—Sarah, the eldest, being her contemporary—Annie’s interest in the arts extended to fashion. For her 1878 wedding to John Innes Kane, Annie wore a stunning ivory and gold satin gown with applied (real) pearls by Charles Frederick Worth (1825–1895), of the eponymous firm Worth of Paris (this gown now in the Museum of the City of New York). Once married, Annie attended the most fashionable events of her era, including the Vanderbilt ball of 1883 (at which the Hewitts were also in attendance), an invitation made socially possible for Annie, as Astor by marriage, by Annie’s relative Lina’s willingness to receive and call on Mrs. William Kissim Vanderbilt, formerly Alva Erskine Smith, as Alva’s family had older money and she produced great social entertainment (other Vanderbilts had not previously been accepted into Lina’s 400).

Annie Schermerhorn Kane’s wedding dress by House of Worth. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

Even though it was Annie’s husband John who sat on the Cooper Union museum’s Advisory Board in the first decade of its existence up to near his death in 1913, she is credited for the actual donation of objects in museum records for gifts dating back to 1910. Although other members of the Advisory Committee are credited with significant gifts in their own names, this double role may be because the Advisory Committee was all male. Given that the founders, the Hewitt Sisters, were women, they wanted to ensure strong financial support through male business connections, so the Advisory Committee, on paper, remained a male bastion. It included J. Pierpont Morgan, Jacob Schiff, and other financial titans who gave funds and objects to the collections. Thus, while John Kane was on the Advisory board, it may be that the gifts in Annie’s name may be his gifts as well, while he was alive; yet far more was bequeathed to the museum when she died in 1926. This is another indication that Annie and John seemed to share a strong bond in their mutual interest in travel and collecting antiques and art, often combined.

From the gifts Annie gave or bequeathed, they appear to have collected European decorative arts from the Renaissance through the eighteenth centuries. Among these gifts was a pair of chairs with a rare verre églomisé coat-of-arms in the back splat (one was also later acquired by Judge Untermyer, who later bequeathed it to the Metropolitan Museum to join a few other pieces). The whole set originally comprised twelve side chairs, two settees, and two pedestals probably supplied by Thomas How (British, active 1710–36) to Nicholas, Fourth Earl of Scarsdale (d. 1736) for Sutton Scarsdale, Derbyshire, England. Research on the history of this set of chairs traces them to an auction of the descendants’ effects at Sutton Scarsdale in 1919, along with the rest of the set and the wood paneling. The firm of White, Allom & Co. may have purchased the set and sold it to the Kanes. White, Allom & Co. served as decorators and suppliers of both French and English antiques and room settings, as well as reproductions to clients in New York and Newport, as well as in England. The firm, like Lenygon & Morant, specialized in decorative arts and architectural elements from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and located was on Old Burlington Street in London.

Scarsdale Side Chair, 1724–36; Attributed to Thomas How (British, active 1710 – 33); England; Walnut and beechwood, gilt pewter, gilt and reverse-painted glass (verre églomisé) panel, mortise-and-tenon construction; H x W x D: 104.1 x 55 x 57 cm (41 in. x 21 5/8 in. x 22 7/16 in.); Bequest of Mrs. John Innes Kane, 1926-22-58

Another Kane donation, a superb English William and Mary cabinet with marquetry probably by a Dutch-trained marquetry specialist, dating to around 1690, also was apparently from the Kane’s English and Continental collecting trips. While the purchase source of the cabinet is not known, another, almost identical cabinet, is now in the Museum of Applied Arts, Oslo, Norway, as a gift from a private collector in Sweden, who must have acquired it about when the Kanes acquired this example—perhaps at an international antiques fair.

Cabinet On Stand (probably England), 1675–1700; Marquetry inlaid, veneered and joined oak, deal, walnut, and other wood, bone, brass; H x W x D: 171.5 x 133 x 55.8cm (67 1/2 x 52 3/8 x 21 15/16in.); Bequest of Mrs. John Innes Kane, 1926-22-43

Despite (or perhaps because of) this restrictive life of the Gilded Age with its social rules, most marriages were not surprises—everyone knew their future in-laws. Nonetheless, Annie Schermerhorn Kane seems to have been known as a forceful person in her own right, much like her contemporary, Sarah Hewitt. In fact, if they did not know each other well before the museum existed, which seems unlikely, Sarah had expected that Annie Schermerhorn’s 1926 bequest to the Cooper Hewitt would allow the museum to select what it liked for its collection, a fact that would suggest a close friendship. When the executors of Annie’s will determined that this was not to be, Sarah wrote a disgruntled letter (now in museum archives in Washington DC) to the executor of Annie’s estate after the latter’s death to indicate her disagreement.

The selection and variety of objects that the Kanes collected on their trips is also reflected in the styles of architecture of the houses they had built. Their New York house built at 1 West 49th Street in 1903–4 was designed by McKim, Mead and White, the premier New York firm of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for Renaissance and classical architecture. Images from this house show a sense of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century taste exhibited by part of their collection, including the arrangements of ceramic pots on the tops of furniture, as would have been stylish with Delft and Chinese pieces collected during that earlier era. The classical-Renaissance style may have influenced their choice in collecting, but such a house was expected to receive collections.

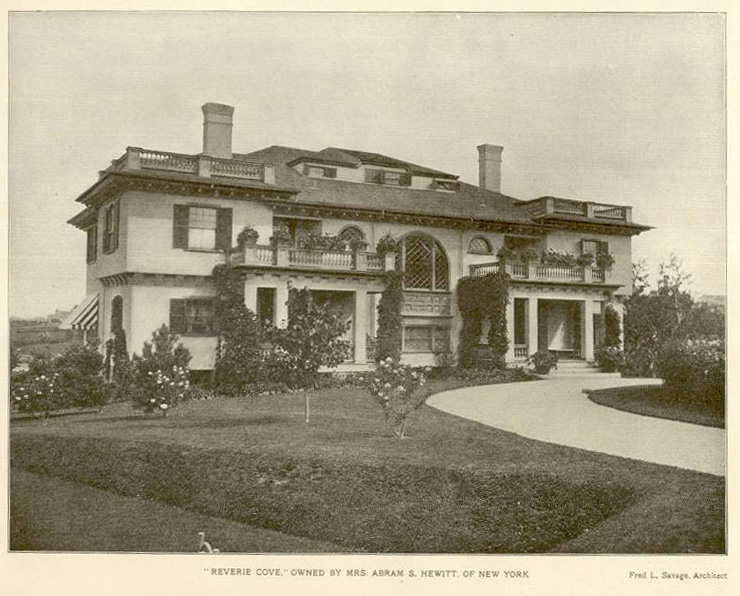

However, the place where their choice of architecture and collections seems to intersect, is in Bar Harbour, Maine, where they also had a “cottage” built at the same time as the New York house. This is the same Bar Harbour where Abram Hewitt purchased a house and had it done over in 1903–4 for his family, including his daughters Sarah and Eleanor, just before his death. The renovation was completed by the same architect, Fred Savage, who created the Kanes’ “cottage.” The term “cottage” ironically referred to large mansions in summer watering holes of the rich and famous, especially Newport, Rhode Island, and Bar Harbour, Maine—the implication being that the owners were so wealthy as to consider these houses just cottages. Bar Harbour developed a similar status to Newport at the same time, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Breakwater or Atlantique, the Kane Bar Harbor “cottage,” Bar Harbor, Maine.

Photograph of Reverie Cove, the Hewitt Bar Harbor “cottage,” Bar Harbor, Maine. Ringwood Manor Collection.

The Kane cottage exterior was in half-timbered neo-Tudor style, while the interior showed more Colonial and Georgian Revival eighteenth-century stylistic sourcing. These styles would have made a fine environment for displaying some of their collections not housed in New York. The house, known both as Breakwater and Atlantique, would have been used for entertaining, although both Kanes also socialized in various clubs to which they belonged. These included The Country Club of Mt. Desert where John Kane was a shareholder. At the same time, Annie was on the Music Committee of the Building of Arts. (fn: Malcolm (Mac) Smith, Mainers on the Titanic, Camden Me and Langham MD, p. 5). Likewise, it is not hard to imagine John Kane pursuing his love of science and exploration in this maritime environment, while Annie promoted the arts with like-minded neighbors, the Hewitts, not far away—both in Bar Harbour and in New York. Annie continued to go up to Bar Harbour until near her death in 1926, the same year the Hewitt’s ceased going there, ushering out an extraordinary era together.

View other pieces donated by Annie Schermerhorn Kane in Cooper Hewitt’s collection.

2 thoughts on “Cooper Hewitt Short Stories: A Formidable Inheritance from a Gilded Age”

Never Break These 5 Dating Rules on November 1, 2019 at 11:53 am

Thanks for the excellent content. Wish to see even more shortly. Thanks again and keep up the great work!

Jeff Sholeen on November 16, 2019 at 11:28 am

Excellent. Thanks for the information about the furnishings and how they likely would have been inherited and acquired and the information about the now nearly vanished world of Bar Harbor. That chair with the verre eglomise panel is stunning, too.