The Palais Royal lies just on the other side of the rue de Rivoli in Paris, well within eyesight of the Louvre. Among other things, this former royal palace is now the seat of the Council of State (Conseil d’État) and the French Ministry of Culture (Ministère de la Culture). Despite its regal name, it was initially designed by the architect Jacques Lemercier in the 1630s as the residence of Cardinal Richelieu (the chief minister to Louis XIII). By the late seventeenth century, the then Palais-Cardinal became the residence for the members of the House of Orléans. During the Regency—a period between the death of the Sun King, Louis XIV, and the coronation of the young Louis XV—the Regent of France, Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans, moved into the Palais. Although his regency only lasted from 1715 to 1723, artistic and architectural commissions nonetheless followed this transition of authority. Of these, Philippe II’s chief architect Gilles-Marie Oppenord oversaw the remodeling of the interior of the Palais Royal, including the Salon d’Angle—the subject of this drawing.

Oppenord was a prolific draftsman, architect, and ornamaniste, who was later canonized as one of the fathers of the Rococo. In his proposed designs in 1719-20 for the Salon d’Angle, Oppenord’s decorative scheme is indebted instead to seventeenth-century Italianate Baroque. This drawing captures his recommendations for a salon à l’italienne to replace the previous design by Jules Hardouin-Mansart of Versailles fame.[1] At the top level, atlas figures (telamons) flank an arched window, and classical statues are on display in individual niches. One can further spot Oppenord’s proposal to carve allegorical trophies on the oblong top panels. In the lower level, Oppenord continues his allegorical mission by including military trophies with plumed helmets and Roman cuirasses, likely a reference to the Regent’s military exploits. In the center is a large arched mirror, its reflective surface captured by Oppenord’s masterful use of gray wash. Just below this is a fireplace, highlighted by the soft glow of light emitted by the Baroque candelabras attached on either end.

Oppenord’s rendering of the fireplace is undoubtedly the highlight of this sheet. The artist has used a deep auburn wash to delineate the veins of the marble. It is likely that the fireplace was to be realized by Nicolas I Dezègre, the marble sculptor to the Regent, in brèche violette, a type of brecciated marble originating from Seravezza in northern Tuscany. [2] Compared to other types of marble, brèche violette was largely used in interiors as its vibrant colors were liable to fade. An example of the polychrome vibrancy of this type of marble can be spotted in an eighteenth-century jardinière at the Getty.

Jardinière, French, 1785; Brèche violette with gilt bronze mounts and brass liners; 21 x 18.4 cm (8 1/4 x 7 1/4 in.); J. Paul Getty Museum, LA; inv. no. 88.DJ.121.1

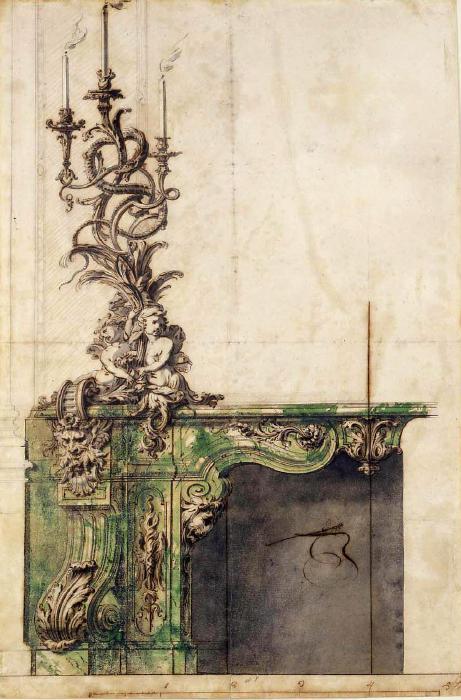

The fireplace in the Salon d’Angle can also be compared to a drawing by Oppenord for the Aeneas Gallery in the Palais Royal (designed ca. 1713-18), now in Waddesdon Manor. The sheet below shows a fireplace to be designed in brecciated green marble, flanked by an elaborate candelabra with sinuous curves, reminiscent of the candelabras on the Cooper Hewitt drawing. Perhaps surprisingly, Oppenord’s drawings were both criticized and lauded in the eighteenth century. The French writer and collector Dézallier d’Argenville remarked that Oppenord’s seductive handling of pen and ink and his near-perfect rendering of ornament surpassed their physical realized counterparts.[3]

Drawing, Half Elevation of the Fireplace for the Aeneas gallery at the Palais-Royal, Designed by Gilles-Marie Oppenord, ca. 1714; Pen and brown and black ink with black chalk and brush and gray and green washes on laid paper; 540 x 358 mm, Waddesdon Manor, UK, Inv. no. 2119

Oppenord’s masterful drawing offers a glimpse at how architectural expressions and ornamental details were mobilized in service of political legitimacy. Although the Salon d’Angle was demolished in 1784, it remains luminous and timeless on this page.

Cabelle Ahn was formerly an MA fellow in the Department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate at Harvard University.

[1] Bedard, Jean-Francois, “Political renewal and architectural revival during the French regency: Oppenord’s Palais-Royal” (2009) Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 68 no. 1 (2009): p. 33

[2] Ibid, p. 41

[3] Dézallier d’Argenville, Vies des Fameux Architectes depuis la Renaissance des Arts 1. (Paris: Debure, 1787), p. 438-9.