In last month’s Cooper Hewitt Short Story, pioneering curator and director Calvin Hathaway applied his art historical expertise to the museum practices at the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, bringing the museum into the twentieth century. This month, Caitlin Condell, Associate Curator and Head of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, takes us to Italy to discuss one of the most significant contributions of European drawings in the early days of Cooper Hewitt’s collection: the addition of the Giovanni Piancastelli collection.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

“Concentrating on my art”

In 1901, the Hewitt sisters made an extraordinary purchase—3,620 drawings by primarily Italian artists and designers, all from the personal collection of Giovanni Piancastelli (Italian, 1845–1926). The collection was the first significant group of design drawings to enter an American museum collection. Sarah Hewitt wrote at the time that “I consider it so important to secure [the collection] for the museum (for in this country all documents of the different periods concerning the Arts of Decoration are entirely lacking)…”

Giovanni Piancastelli. Castel Bolognese, Museo Civico.

Although Giovanni Piancastelli began his career as an artist, it was through his curious skill as a collector that he figured so prominently in shaping the collection of the Cooper Union Museum in the early years of the twentieth century. Yet the dual roles of artist and collector were not so easily distinguished from each other for Piancastelli. His early training began at a convent on the outskirts of Ravenna, Italy, where he apprenticed with a friar and learned to draw and paint. He continued his professional artistic training, first at the Scuola di Disegno in Faenza and then at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. But Piancastelli’s artistic career was halted by a period of military service from 1866–71. It was after this period that he was hired by Prince Marcantonio Borghese as a tutor of drawing and painting for the royal children.

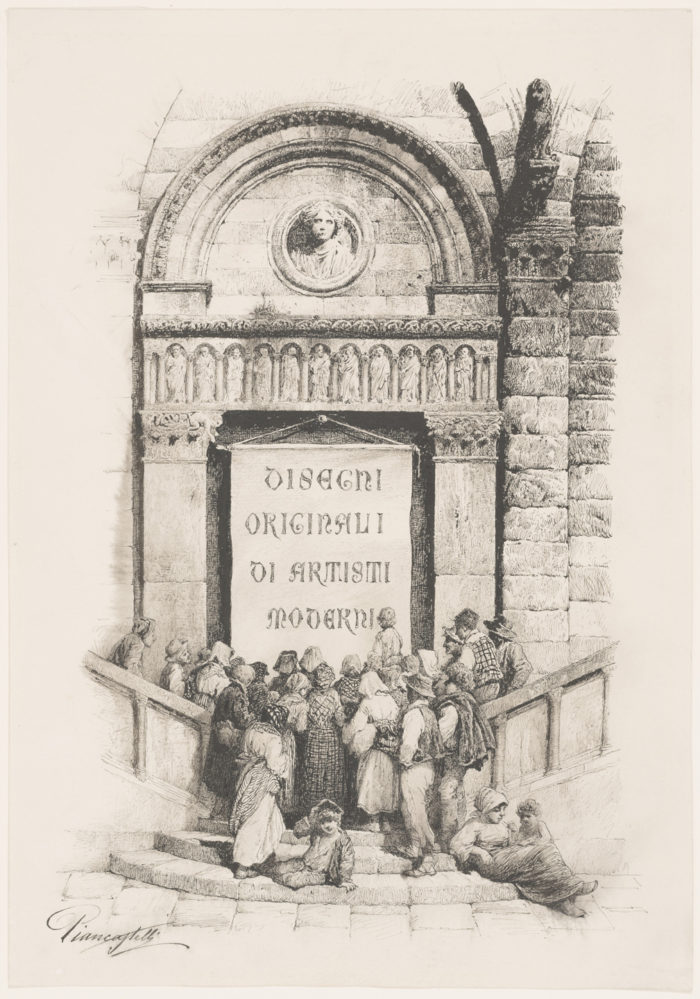

The sole example of Piancastelli’s artwork in Cooper Hewitt’s collection. Drawing, Title Page for an Album of Drawings, “Disegni originali di artisti moderni,” ca. 1880–1920; Giovanni Piancastelli (Italian, 1845–1926); Pen and black ink, charcoal on thick white wove paper; 40 x 28 cm (15 3/4 x 11 in.); Friends of the Museum Fund, 1976-119-1

In the capacity of artistic tutor, Piancastelli traveled with the Borghese family as they moved between their estates in Tuscany and Lazio. He soon became involved in the decoration of Borghese’s villas, as well as the homes of some of Borghese’s wealthy acquaintances. His connections established through buying art and furnishings for these decorative commissions gave Piancastelli particular access to the burgeoning antiquities market, and he began to assemble his own private collection of drawings. Piancastelli also frequently accepted collections of drawings as payment for his services.

After Marcantonio Borghese’s death in 1886, Piancastelli took on the responsibility of reconstructing the Borghese collection and transferring it to the Villa Pinciana in Rome—more commonly known as the Villa Borghese—and he became the first director. His work with the Borghese collection increasingly occupied his time. In January 1901, Piancastelli wrote mournfully of his inability to focus his attention on his own collection of drawings as well as his artistic practice: “[I am] an artist and painter myself. I do not have the time to study and illustrate my own drawings. It is indeed a great loss of time for me to research my collections.” For this reason, Piancastelli said, he had decided to sell his collection of more than 12,000 drawings. “The only reason that I am parting with this collection,” he wrote, “is to free myself from the continuing distraction that keeps me from concentrating on my art.”

Drawing, Ceiling Design Depicting Iris and the Rainbow, 1810–25; Designed by Felice Giani (Italian, 1758–1823); Pen and brown ink, brush and watercolor on off-white laid paper; 33.5 x 30.8 cm (13 3/16 x 12 1/8 in.); Museum purchase through gift of various donors, 1901-39-1807

When word reached the Hewitt sisters that the collection of drawings was for sale, they immediately set out to pursue it. Their network of friends was pressed into service. First, they enlisted the advice of writer F. Marion Crawford, an American born in Italy who had relocated to Italy in the 1880s. (Crawford was also a lifelong friend of art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner and actress Sarah Bernhardt.) Crawford suggested that the Hewitts solicit the services of Waldo Story to negotiate the purchase from Piancastelli. Story was an American sculptor who had also spent much of his life in Italy, having been raised in the Barberini Palace in Rome. Communications by cable and letter ensued, and the Hewitt sisters soon learned that Piancastelli had divided his collection into six lots. They immediately set their sights on lot number five, which Piancastelli had estimated as 1,800 drawings of decorative and industrial art. “Up to now,” Piancastelli wrote in response to their inquiries, “few thought to collect documents of this art that now receives so much attention. This is the collection which presently occupies all my study and I am most unhappy to part with it. Due to continuing research on a daily basis,” he added, “it will in time grow to have a unique value.”

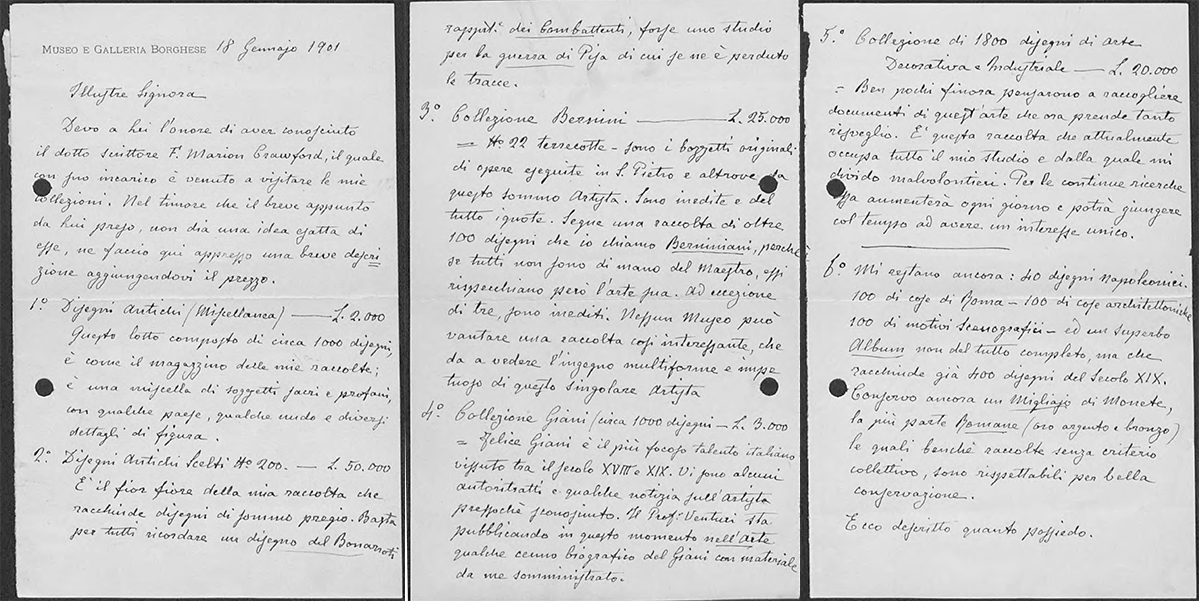

Three pages of a January 1901 letter from Piancastelli, in his lively script, to “Illustrious Signora”—Sarah Hewitt—in which he provides descriptions of each lot available for sale from his collection, notably the decorative and industrial art drawings and his colorful identification of Felice Giani as “the most fiery Italian talent.” Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

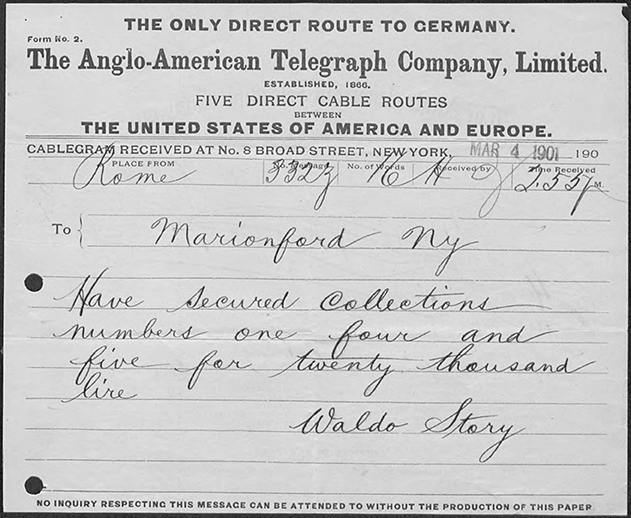

Piancastelli had priced the lot of decorative drawings at 20,000 lire. The Hewitt sisters discerned that they might bargain, and decided to ask Piancastelli what was the lowest price he could offer for the decorative drawings lot, as well as the lots containing approximately 1,000 drawings by the architect Felice Giani (lot number four, priced at 3,000 lire) and the lot of miscellaneous “old drawings” that featured both sacred and profane subjects (lot number one, priced at 2,000 lire). The sisters cabled Story directly at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome on February 28, 1901. Story cabled back that Piancastelli “will accept twenty thousand lire for three collections numbers one four and five leaving out number three.” The bargain was accepted, and the sisters arranged for the bank transfer.

Cable from Waldo Story to F. Marion Crawford confirming the purchase of three lots from Piancastelli, March 4, 1901. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Sarah Hewitt lost no time in drafting a letter with a hearty dose of instructions, in her typical manner, on how the works should be packaged:

“Would you therefore kindly see that the collections are properly packed (by some suitable reliable person who is accustomed to pack [sic] valuable drawings, with tissue paper between each drawing so it cannot possible [sic] get rubbed if it shifts) in a well made heavy wooden case, lined throughout with block tin, soldered together tightly along the edges, so that no moisture can possibly get at the drawings. This inside tin case should be heavily lined with a number of layers of thin paper of a quality that will absorb any moisture that may be caused by the condensation of the atmosphere on the inside of the tin box.”

Meanwhile, Piancastelli wrote his own letter bristling with enthusiasm for the purchase, but with some cautionary asides. “Not one of the 4,000 pieces of paper must go in the wastepaper basket,” he declared. Certainly, if he had read Sarah’s exceptional packing instructions, he would not have feared for the fate of any of the drawings.

As Piancastelli had promised, the collection was full of gems. Among the highlights were the unbound sketchbook drawings by Stradanus for his Nova Reperta, more than one hundred sketches by the architect Carlo Marchionni for the Villa Albani, and major collections of drawings by the influential decorative painter Felice Giani and the architect Giuseppe Barberi.

Drawing, Sketchbook Page with Elephants Attacked by Troglodytae and a Stag Hunt, ca. 1590; Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus (Flemish, active Italy, 1523–1605); Pen and bistre ink, brush and brown wash on white laid paper; 21.8 x 15.7cm (8 9/16 x 6 3/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of various donors, 1901-39-163

With limited funds, the Hewitt sisters do not appear to have considered purchasing Piancastelli’s collection in its entirety. In 1904, Piancastelli sold the remainder of his collection to the Brandegee family in Boston. Then, in 1938, Mary Brandagee wrote to the Cooper Union Museum’s director: “I have decided to part with this collection, and as I should like it to be used in an institution where there are many students, I am offering them to you.” For less than $1,000, Cooper Union Museum for the Decorative Arts purchased the remaining 8,226 drawings from Piancastelli’s original collection, thus reuniting nearly the whole of the collection at the Cooper Union Museum.[1] The purchase in 1938 included important collections of drawings by Italian architects and set designers, most notably those by the Bibiena family.

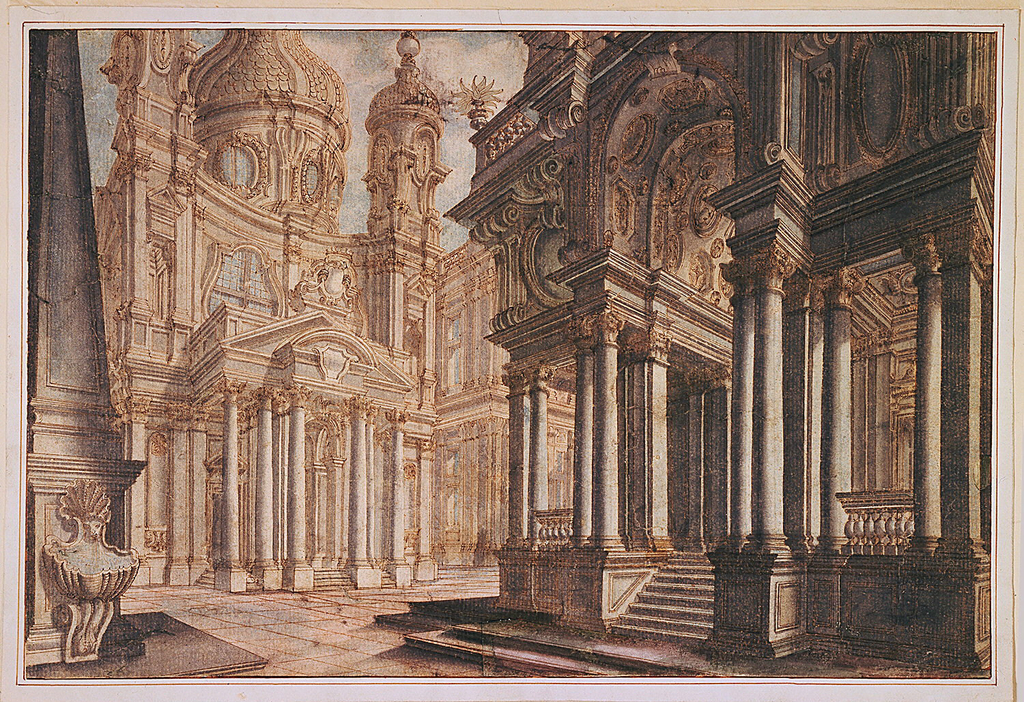

Drawing, Stage Design: A Town Square, ca. 1719; Francesco Galli Bibiena (Italian, 1659–1739); Pen and brown ink, brush and gray wash, blue, pale rose watercolor on white laid paper, lined; 28.7 x 42.4 cm (11 5/16 x 16 11/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of various donors and from Eleanor G. Hewitt Fund, 1938-88-50

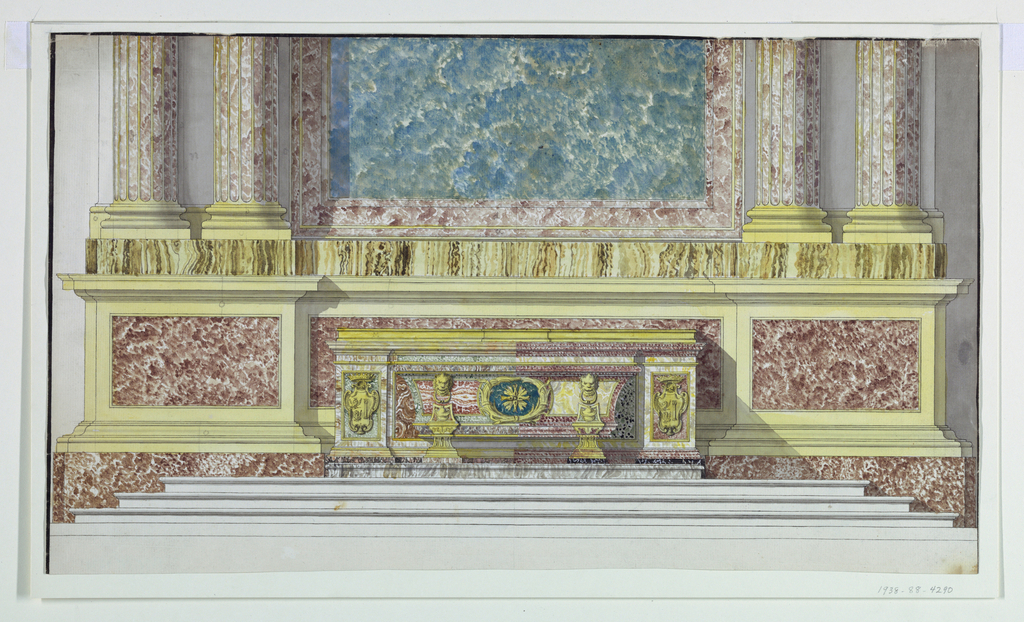

They also included singular works, such as Mario Asprucci the Younger’s drawing for the Altar Mensa for the Borghese Chapel in the Santa Maria Maggiore.

Drawing, Altar Mensa for the Borghese Chapel, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, Italy, ca. 1795; Designed by Mario Asprucci The Younger (Italian, 1764 – 1804); Pen and black ink, brush and watercolor over black chalk on paper; 29.5 x 50.7 cm (11 5/8 x 19 15/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of various donors and from Eleanor G. Hewitt Fund, 1938-88-4290

Piancastelli was keenly aware of the uniqueness of his collection. “Each [drawing],” he wrote, “recalls a thought or the research of a composition, of a form, of a line, or the trace of an idea. It is a language of art which the artist experiments before developing the idea.” Piancastelli remained, at heart, a dedicated collector. Of his plans once his collection had been sold, Piancastelli wrote:

“I foresee that I will be a non-repentant sinner because as soon as I will have money, I will go to Milano to acquire other lots of drawings that are there, and I will continue avidly to collect so that in a short time, I hope I will have put together a new collection of decorative arts perhaps more interesting than the first.”

He was keenly aware, as the Hewitt sisters were, that the opportunities to acquire drawings required quick action. “In Italy people sleep and only a few study,” Piancastelli wrote. “One must collect before the alarm clock rings.”

[1] Several drawings, most notably those by Bernini, were not included in the sale to Cooper Union Museum for the Decorative Arts.

SOURCES

De Santi, Samantha and Valentino Donati. Giovanni Piancastelli: Artista e Collezionista, 1845–1926. Faenza, Italy: Edit Faenza, 2001.

Letter from Sarah Hewitt to Waldo Story, March 6, 1901, held by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Newman, Vianna. “Giovanni Piancastelli, Collector and Artist.” Cooper Hewitt Object of the Day, September 1, 2015. Accessed May 25, 2017. http://uchicagolaw.typepad.com/beckerposner/2010/02/double-exports-in-five-years-posner.html.

Letter from Giovanni Piancastelli to Sarah Hewitt, January 18, 1901, held by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Letter from Giovanni Piancastelli to F. Marion Crawford, March 8, 1901, held by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Symmes, Marilyn. “‘Beauty as Applied to the Useful’: Drawings at the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution.” Master Drawings, Vol. 42, No. 1, Drawings in American Museums (Spring 2004), pp. 37–57.

—–. “Collection for Inspiration and Instruction: Drawings at Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.” The International Review published by The Drawing Society, Vol. XVII, Nos. 4–6 (November 1995–March 1996), pp. 73–79.

All correspondence in the records of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

2 thoughts on “Cooper Hewitt Short Stories: Collecting Before the Alarm Clock Rings”

Julius Glaihengauz on June 23, 2017 at 12:41 pm

Dear Ms Condell,

In this very informative article you mention in the note 1 the drawings by Bernini.

I will very much appreciate if you tell me what you know (or direct me to the source of this knowledge) about the Bernini drawings in the Giovanni Piancastelli collection.

Sincerely yours,

Julius Glaihengauz

JEROME GARCHIK on January 13, 2023 at 11:54 am

You should direct your inquiry to the Harvard Fogg Museum in Cambridge, Mass, which

has a famous Bernini set of 25 terracota prototype sculptures also purchased by a US

private collector from Piancastelli.