In celebration of Women’s History Month, Cooper Hewitt is dedicating select Object of the Day entries to the work of women designers in our collection.

Helen Dryden (1883-1972) was born in Baltimore and studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her early career was spent as an art teacher, costume designer and fashion illustrator, exemplifying Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles for the covers of Vogue and Delineator magazines. Her artistic output ranged from creating Japanese-style prints, children’s books, and theatrical costumes. A change was coming; new interest and a new talent emerged: Dryden’s career path turned to industrial design. In browsing the Cooper Hewitt Library’s electronic resources and periodicals further, I discovered her expanded role as an artist.

In the Gallery column of Advertising Arts of March 1932, her “retirement” from illustration was noted. A good commercial designer gets paid much better than a cover artist. Interestingly, Helen Dryden and famous industrial designer Raymond Loewy both worked for Condé Nast, Vogue’s publisher, in the 1920s. They would meet again and work together on the most successful work of Dryden’s career: Studebaker automobiles.

In the late 1920s, she worked as a designer for The Dura Company in Ohio. They made chrome decorative objects into the 1930s, including chrome fixtures like these very modern faucets (see below). She also did work for Revere, who made kitchenware in aluminum, brass and copper. She also designed glassware and continued designing textiles.

Advertising Arts, July 9, 1930. P.49 “Glorifying the Bathroom Tap” Designs by Helen Dryden

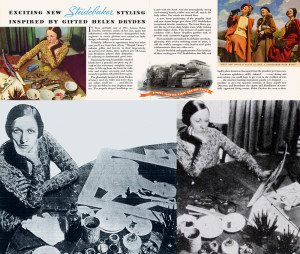

Success, fame and money came with Studebaker. In 1936, Dryden was acclaimed as the highest paid woman artist in America, earning a salary of over $100,000 per year. Her earlier fame in publishing was such that Studebaker was counting on her name recognition influencing potential sales to women automobile buyers.

A Studebaker publicity brochure, 1937.

Loewy and Dryden collaborated; he designed the exterior of the new 1936 and 1937 luxury car models; she designed the interiors, including the instrument panels. She stated her ideas on car design: “the modern automobile… is worthy of serious study as a thing apart from any other means of transportation. It deserves new ideas in decoration, typifying its own individual period.” Dryden also added her thoughts concerning designing for women as consumers: “With womankind influencing the sale of automobiles in greater numbers today than ever before, it is essential to consider what will have the greatest appeal to her taste and what will best meet her requirements.”

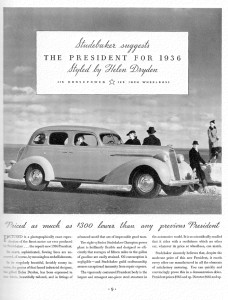

Fortune Magazine Studebaker advertisement, Vol. 13, no.1. Jan. 1936.

The large top headliner box boasts “Styled by Helen Dryden,” while the ad copy reads “In its singularly beautiful, lavishly roomy interior, the genius of that famed industrial designer, the gifted Helen Dryden, has been expressed in fine fabric, beautifully tailored, and in fittings of advance motif that are of impeccable good taste.” Similar ads appeared in many magazines and newspapers, all mentioning Helen Dryden by name. Unusual, I think, to publicize a specific designer, especially a woman, in car advertising.

Sadly, suddenly and mysteriously after 1940, her career faded and she vanished from the public eye. Her story ends with her living on welfare in an East Village hotel in New York City. She had been a regular at New York A-list social gatherings and charitable fundraisers, and earned a reputation as a leading expert on contemporary design and as the last word on contemporary good taste. I wonder what happened to halt this multi-talented and prolific artist and designer.

Elizabeth Broman is a Reference Librarian at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library. Weixin (Joyce) Jin assisted with research. She is a graduate student in the Design History and Curatorial Studies program at Parsons / Cooper Hewitt and works in the Smithsonian Design Library.

4 thoughts on “Helen Who?? Her Life as an Industrial Designer (Part Two)”

William on March 25, 2016 at 11:42 am

I am very interested in the cars that she took part into design, and I am wondering is this car brand still alive today?

Elizabeth Broman on March 25, 2016 at 11:46 am

The last Studebaker automobile rolled off the Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, assembly line on March 16, 1966 . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Studebaker

Michael Leonard on April 13, 2020 at 2:27 am

Have you ever heard of “Wikipedia”?

Sarah Marie Horne on April 12, 2016 at 12:26 pm

The account of Dryden and Lowey’s collaboration with Studebaker is not quite correct. Dryden was retained as a consultant in 1935 – designing interiors and, to some extent, the exteriors as well. Lowey was retained in 1936, but his influence does not appear until the 1938 models. This is the year that Studebaker’s have Lowey exteriors and Dryden interiors. For the 1936 and 1937 models, Dryden is the primary design and style consultant.

Learn more by viewing my talk at the annual Parson’s/Cooper Hewitt Graduate Student Symposium on the History of Design. See the second panel:

http://livestream.com/TheNewSchool/Voorsanger-Symposium-Showing-Off?t=1460337248737