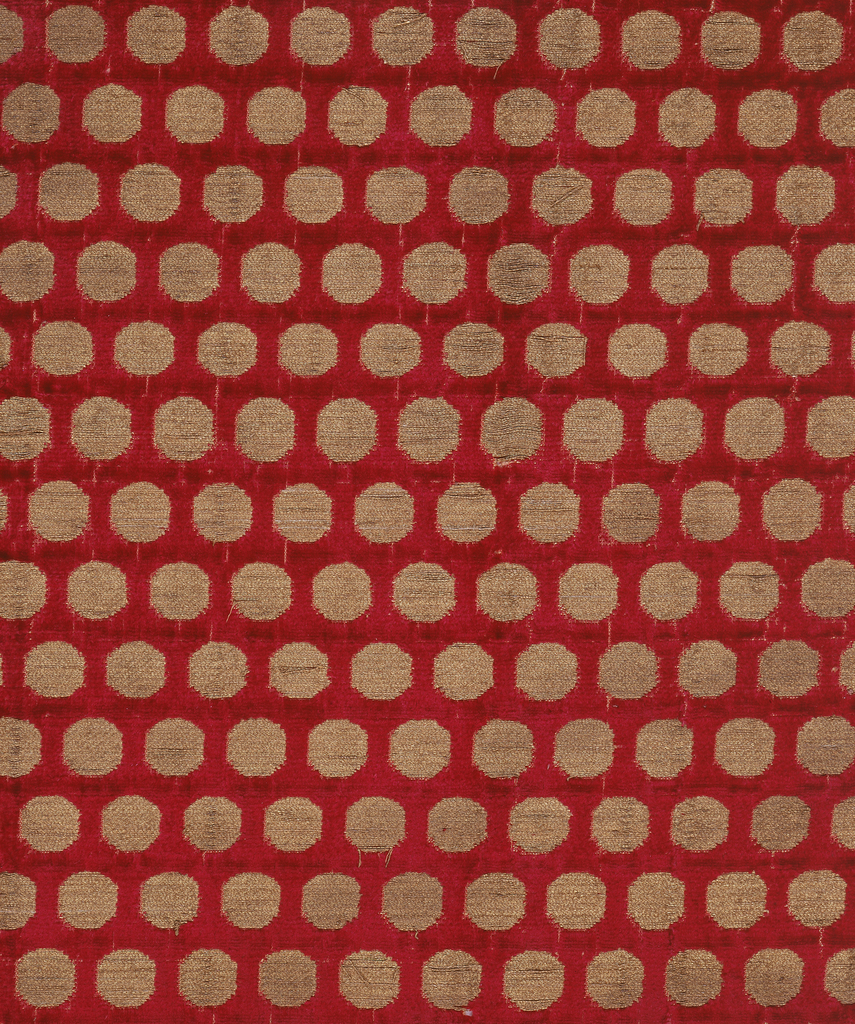

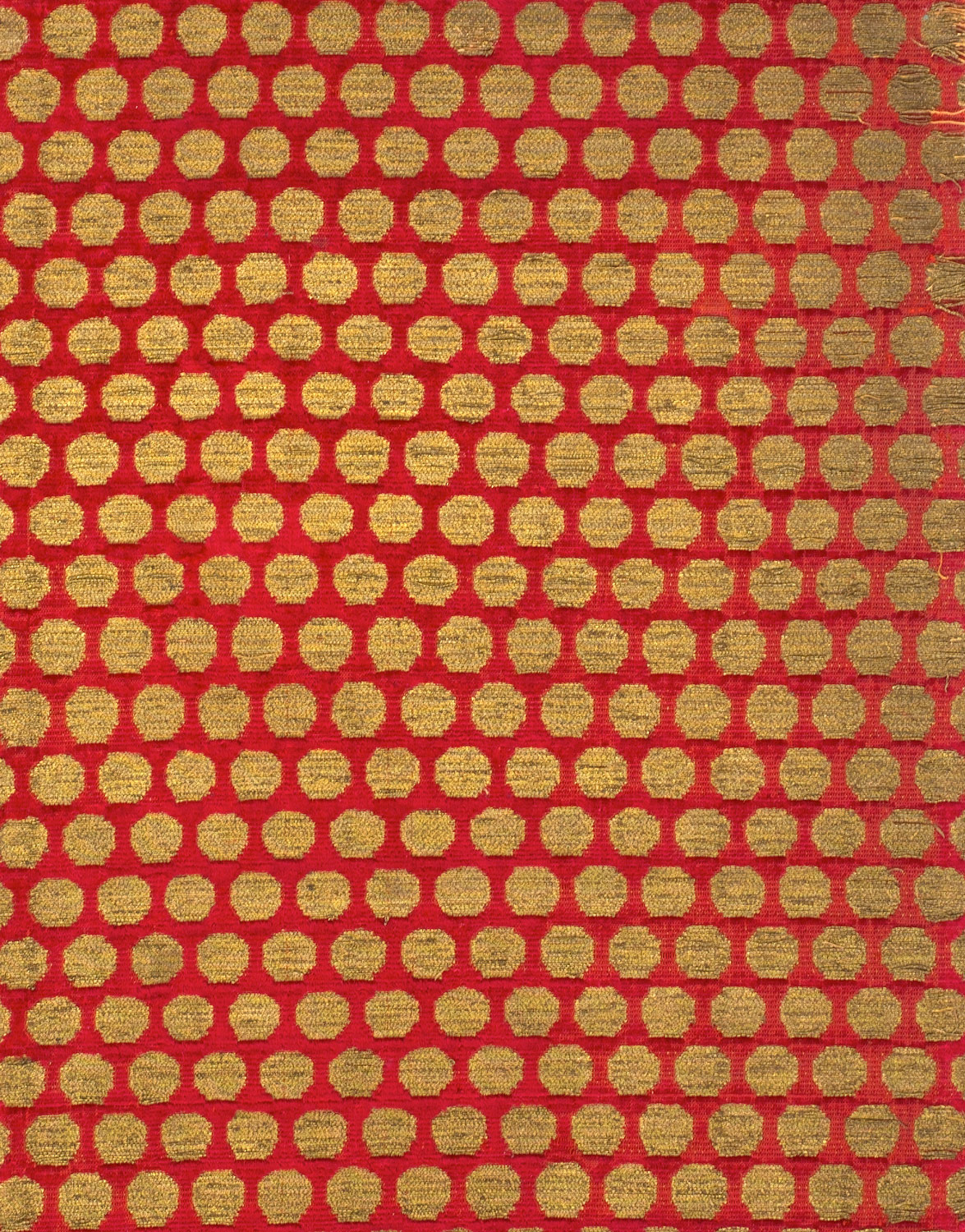

This sumptuous red velvet with gold disks embodies what we can learn from textiles by looking, comparing, deconstructing, reconstructing, and then interpreting our observations. Milton Sonday, my predecessor in the Textiles department at the Cooper-Hewitt, is a master of this methodology and has spent years employing it and teaching it to researchers and curators around the world. Fortunately, of his published articles, one is about this velvet as it relates to other velvets of similar patterning, material, and structure, and demonstrates how an understanding of structure and technique supported by historical research can lead to a rich story of textile making.

Brocaded velvet, Probably Italian, 14th century. Brocaded velvet of silk and metal thread. 23 x 9 in. (58.4 x 22.9 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1946 (46.156.72).

The article, “A Group of Possibly Thirteenth-Centry Velvets with Gold Disks in Offset Rows”, appears in the The Textile Museum Journal 1999-2000 (vol. 38 and 39, pp. 101-51) and features a group of twenty-one textiles from eleven different institutions (the Met’s object is above), all similarly patterned and mostly dating from the fourteenth or fifteenth century. Geographic attributions for these textiles span Italy, Spain and regions east of the Mediterranean. Sonday divided his study into two sections: criteria that can be determined by looking at the fabric–structure, warp and weft order, details of the patterning techniques, contour of disks, layout, and pattern repeat. The second section is about theoretical features: loom types and set ups to weave these structures and pattern. In addition, he relied on writings about Islamic silk of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

Sonday’s findings suggest a number of possibilities about these fabrics – not absolutely conclusive (except for the information related to structure) – but revealing about taste, style, and rarity of the textiles. In his summary, Sonday explains that “Reference in Italian inventories of the period confirm the use of fabrics with the pattern of offset rows of disks. Judging from the number of pieces extant, this pattern was favored. Moreover, the fact that in an Italian inventory dated 1295 one cloth is described as a Tartar velvet is backed by references to the weaving of velvet far to the east of Italy—specifically in or around the city of Tabriz [in Iran – a center for the production of luxury textiles before the arrival of the Mongols in the mid-thirteenth century].” Tartar silks were popular among the rulers of Europe during the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries due to the reopening of the Silk Road and the profusion of gold in these textiles. The possession and wearing of these fabrics signified wealth and became a part of formal court dress. The gold disks of the pattern may allude to small gold coins or medallions.

In the end, Sonday gives us a methodology for analyzing any textile and reinforces the need to look, look, and look again.