In last month’s report we looked at what was popular on our collection site before we launched our new alpha version.

I can happily report that traffic to our collection is up by almost a factor of three. That’s three times as much traffic to our collection than before. Even when we exclude the burst at the announcement!

Visitors exploring our collection now represent 36% of Cooper-Hewitt’s pageviews (up from a previous 12% in August) and 15% of overall site visitation (up from just 3%). This shift towards the collection is critical for museums to make online—often it is only the collection that makes an institution significantly different online from any other type of media or resource.

Part of this is due to the increased discoverability of objects—every object now has its own discrete URL—but we are also seeing a lot more social sharing of objects which is leading to entirely new visitors. We’ve been sharing them more ourselves, and you can see some of the stranger objects on our “Random Button” board on Pinterest.

We had some conjecture about whether or not the same objects would be popular. Or whether, with an increase in traffic, we’d also see different behaviours.

Let’s take a look.

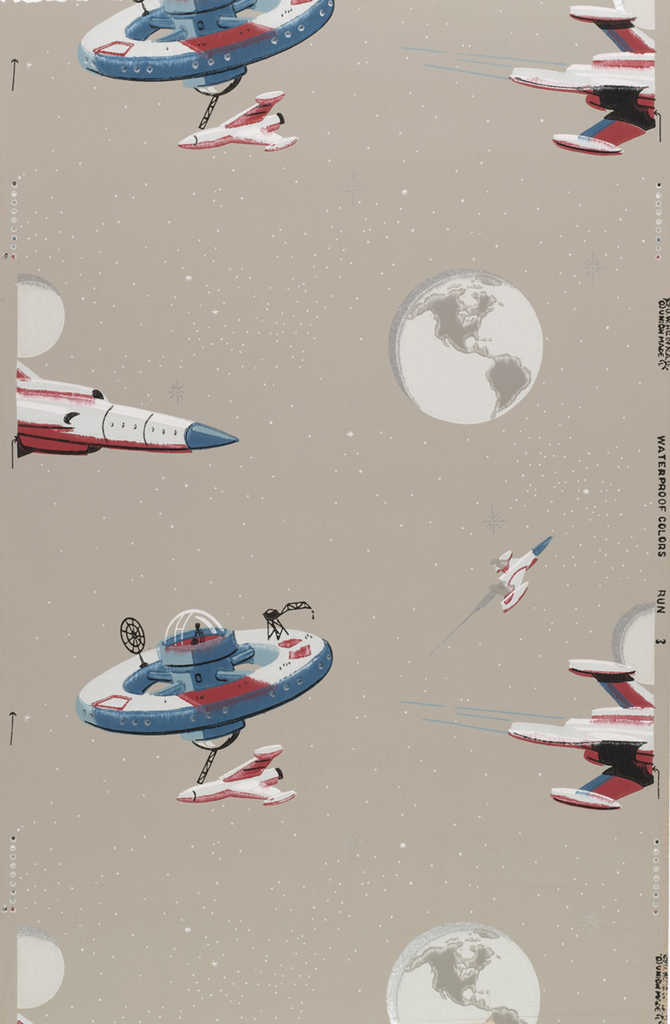

- Sidewall: Wallpaper with space stations and rockets, ca. 1950.

This wallpaper was featured by Smithsonian’s Seriously Amazing campaign and much of its traffic came in from Twitter. It is very much an outlier compared to the other most popular objects this month.

- Prototype Toy Block: Build the Town, Ladislav Sutnar, 1941.

This famous children’s toy, designed by Ladislav Sutnar, was included in MoMA’s recent Century of the Child exhibition. This object has had consistent interest on the new collection site with daily visitation primarily coming in through Google searches.

- Tsuba, 1688–1703.

This late 17th-century Japanese tsuba, or sword guard, has also been consistently popular. It’s one of 663 different tsuba we have online at the moment (have a look at this 1980 catalogue of devoted to our tsuba collection), but there’s no clear reason why this one in particular receives more traffic than the others. Interestingly, it is an object that is never the start of a visitor’s journey through our site, but something they chance upon as the move through it. This type of serendipitous discovery was one of the main aims of the new site architecture.

- Textile: Past, Present, Future, Ulf Moritz, 1989.

We mention this textile in the introductory text on the collection site.

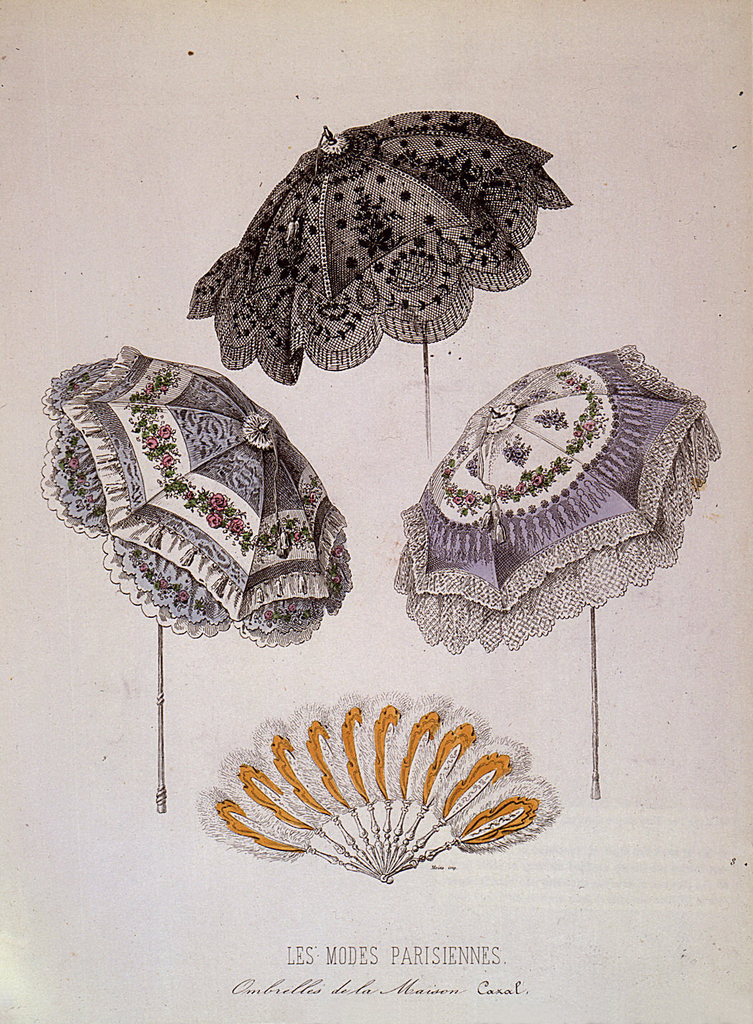

- Print: Parisian Fashion [Le Mode Parisiennes], n.d.

This popular object seems to be chanced upon rather than sought.

And, that rounds out the top five.

But that’s not all.

Google Art Project

In April, Cooper-Hewitt shared 1600 collection records with Google Art Project. These objects were primarily ones without known rights limitations, and the opportunity for them to circulate among those of other museums worldwide was too good to pass up.

A few weeks ago we got access to usage statistics on those objects and here are the top five for October.

- Interior with a man reading at his desk, A. L. Leroy, 1827.

- The Life Line, Winslow Homer, 1882–3.

- Sky at sunset, Jamaica, West Indies, Frederic Edwin Church, 1865.

- Design for the Facade of Societé Immobilière de la Rue Modern, No. 6, Hector Guimard, 1909.

5. Miser’s purse, Unknown maker, 1810–40.

What is interesting about these is that none of them rank anywhere near the top of the most popular objects on our own site. Unsurprisingly, this confirms our assumptions that Google Art Project users would exhibit different behaviour to those on our own site. Google Art Project is reaching new and different audiences—on initial examination, a far more international audience.

Given these results we are going to keep a close eye on what is of interest to those audiences who are and are not aware of what we have. It is already obvious that our collection’s greatest challenge is simply that the public isn’t aware of the gems inside it. I expect most museums face exactly the same challenge.

One thought on “What’s popular in a museum collection after a user interface change?”

M. P. Feitelberg on April 1, 2022 at 2:04 am

Fascinating. Thank you for these insights! I would love to know what else you’ve learned, now that we’re ten years out — with two years of pandemic seclusion to draw upon.