Written by Andrea Lipps, Jessica Walthew, and Eric Rodenbeck

In 2021, Cooper Hewitt collected the Smithsonian’s first live website, Stamen Design’s Watercolor Maps, into its Digital Curatorial Department. Watercolor Maps is a web-based, open-source mapping tool launched by Stamen in 2012 that renders OpenStreetMap data with the hand-hewn textures and visual effects of watercolor paint.

For the acquisition, the museum made a fully functioning, interactive, and open-source copy of the site to ensure its long-term live access, available at http://watercolormaps.collection.cooperhewitt.org.

Like any acquisition, the museum is dedicated to maintaining and evolving the site into the future. Stamen’s original site continued to live alongside the Smithsonian’s version until Stamen announced in August 2023 that it was taking down its much-beloved mapping tools. Stamen transferred responsibility for hosting the tiles to Stadia Maps and, for the Watercolor style, also to Cooper Hewitt.

About Watercolor Maps

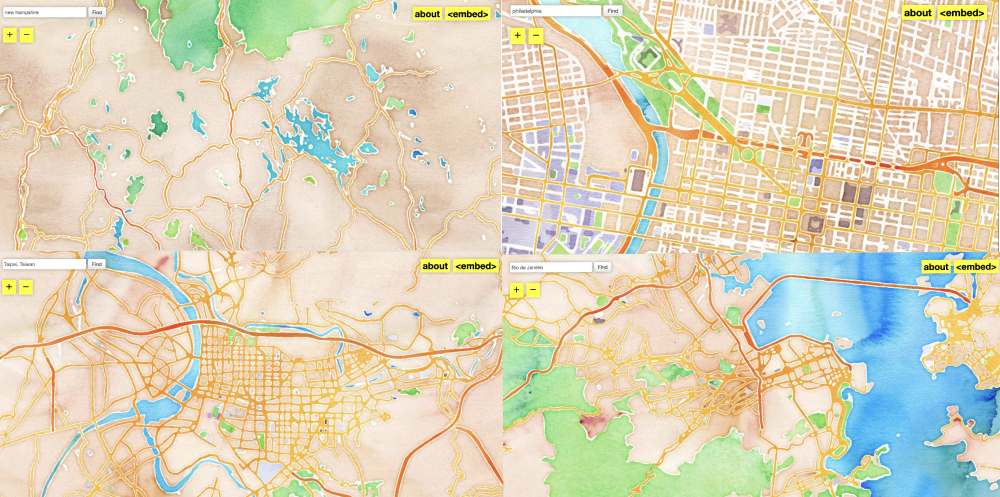

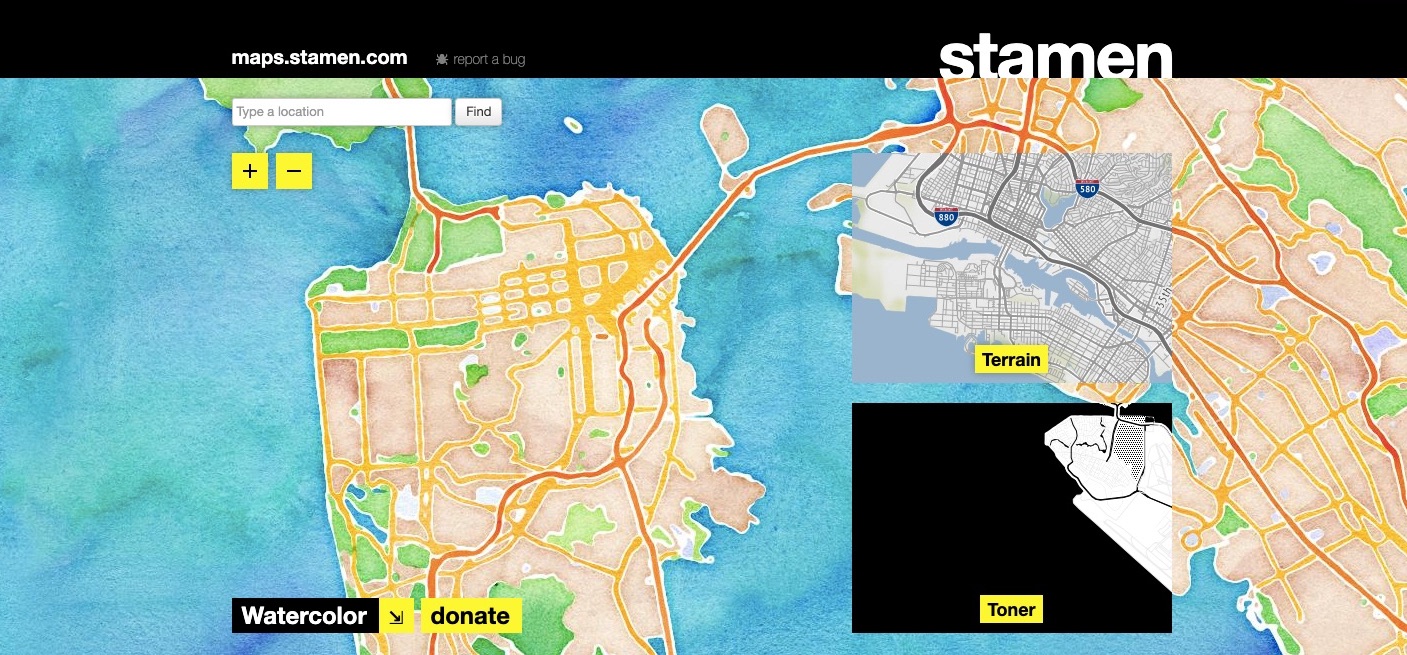

Stamen Design is a pioneering data visualization and cartography firm and won the prestigious National Design Award for Interaction Design in 2017. Watercolor Maps is one style in a series of Stamen’s well-known digital maps—open-source mapping tools that are searchable, zoomable, and downloadable. The map styles are built on OpenStreetMap data and are freely available for use wherever OpenStreetMap data is displayed. Stamen designed the maps with free public access as a fundamental goal. The maps render the world in several styles from which users can choose, as seen in the screenshot below—a conventional terrain map, a high-contrast black-and-white toner map, and the watercolor style that renders the digital map as a watercolor painting.

Screenshot (taken January 11, 2021) of the maps.stamen.com/#watercolor landing page, which displayed the other two map styles in the series: Terrain and Toner.

Watercolor Maps, in particular, breaks from traditional online cartography by emphasizing aesthetics at the same level as representational accuracy. The marks on the screen are based on real-world data, and the mapmakers have taken liberties with the rendering process to emphasize that the maps are the product of human-computer interaction, not the end result of faceless robotic activity.

Water is rendered in blues mixed with turquoise and violet; green spaces are yellow, forest and muddy greens; terrain is a combination of peaches, browns, and violet; motorways are oranges, reds, and browns; buildings are lavender gray. The colors retain the texture of rough paper. A wet-wash technique results in darker tones where the pigment accumulates and disperses in lighter hues.

The aesthetic recaptures the tactility and hand-colored nature of physical maps, qualities that are often lost with digital maps, while being rooted firmly in the open data ethos and global nature of the OpenStreetMap project. The maps have been ubiquitous on the web and used in thousands of mapping projects around the world.

How did the museum collect a website?

To bring the complex work into the digital collection, we archived the more than 56 million map tiles and original code in the museum’s secure Digital Asset Management System (DAMS) and copied the project’s repositories to our collection Github, an online platform to store and manage code. We also generated documentation around our efforts, including a designer interview and video documentation navigating the original site. We acquired digital prints into our Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design Department, made by Stamen Design when Watercolor Maps first launched.

In order to create the live version of the website, our Smithsonian team worked closely with Eric Rodenbeck, Stamen’s Founder and Creative Director, and his team. We actively sought to acquire Watercolor Maps not as an archived site, similar to how the Internet Archive or Library of Congress archives websites, but as a live site in order to prioritize free access and interaction—hallmarks of the original site.

Notably, Cooper Hewitt’s branch of the site disentangled Watercolor Maps from Stamen’s other web-mapping styles. We copied the watercolor map tiles from Stamen to Smithsonian servers; relinked the code to the new server locations, now under the Smithsonian’s control; and made required security modifications, updating the site’s http protocol to the more secure encryption of the https protocol (a web standard that began in 2014).

In the first iteration of the site for the 2021 acquisition, we made minimal but critical changes from the original site. Removing the black band located across the top of the original site enabled us to feature more of the watercolor map and signal its disentanglement from the other web-mapping tools. Options to “Donate” funds and to “Buy” objects were removed and replaced with an “About” section. A key goal for institutional collecting of digital objects is to document and reveal to the public as much of our process for collecting and preserving as possible.

We recentered the site’s landing page to feature Cooper Hewitt’s New York City location rather than Stamen’s San Francisco headquarters. This slight modification sought to reflect the site’s literal and visible acquisition from its native Stamen ecosystem to the Smithsonian’s collection.

Screenshot (taken August 23, 2023) of Cooper Hewitt’s Watercolor Maps landing page.

In the first iteration, we maintained the “Embed” function of the original site to ensure usability as it was initially designed. And we made the site publicly accessible and open to all, critical to the ethos of the project since its launch.

One quirk about the way the tiles were originally generated has left its mark on the acquisition. Rather than generating tiles for the entire world (a time-consuming and expensive process), Stamen only generated tiles as they were requested by viewers of the map. These tiles were then cached to save processing time and cost. The result meant that places like New York and San Francisco, which were viewed by many users and at many zoom levels, are fully rendered. Other places like rural China or rural United States, which were never viewed before the renderer was disabled in 2015, are blank when zoomed in closely. In this way, Watercolor Maps effectively encapsulated its own historical use by showing where users searched (rendered tiles) and where they did not (blank tiles).

Evolving stewardship of Watercolor Maps

Digital collecting profoundly changes the nature of stewardship in museums. Cooper Hewitt is involved in the continued evolution of our copy of the site and remains committed to maintaining public access to the Watercolor map tiles, even as transitions in mapmaking continue to occur.

In 2023, when Stamen announced it would no longer host the map tiles and transferred them to Stadia Maps, we updated Cooper Hewitt’s collected version of the site. We rewrote the “About” page and replaced the “Embed” function with “How to,” which included clearer instructions on how visitors might use the project. The site remains accessible and free to use. Users are welcome to take screenshots of the maps, embed them, or, for more advanced developers who want to make their own maps with these tiles as the base map, use the tiles from our servers in independent projects. Examples of html can be found on the Cooper Hewitt Collection Github.

Andrea Lipps is associate curator of contemporary design and head of Digital Collecting at Cooper Hewitt.

Jessica Walthew is a conservator at Cooper Hewitt working with the product design and decorative arts and digital collections.

Eric Rodenbeck founded Stamen Design in 2001 and since then has served as the organization’s Founder and Creative Director.

More resources

In May 2021, Cooper Hewitt issued a press release announcing the Watercolor Maps acquisition.

The digital work’s collection record is available on Cooper Hewitt’s collection site, as are collection records for the Watercolor Maps corresponding prints, which were acquired into the museum’s Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design department.

Cooper Hewitt collection’s Github repository includes our Watercolor Maps repo.

Eric Rodenbeck, Founder and Creative Director of Stamen Design, discussed the project with the museum in this edited designer interview.

Stamen Design’s legacy Watercolor Maps site remains live. In August 2023, Stamen announced its partnership with Stadia Maps, who now provide hosting of Stamen’s map tiles, including Watercolor as well as original raster and new vector versions of Stamen’s other popular styles. For technical support with these map tiles moving forward, visit Stadia’s how to page.