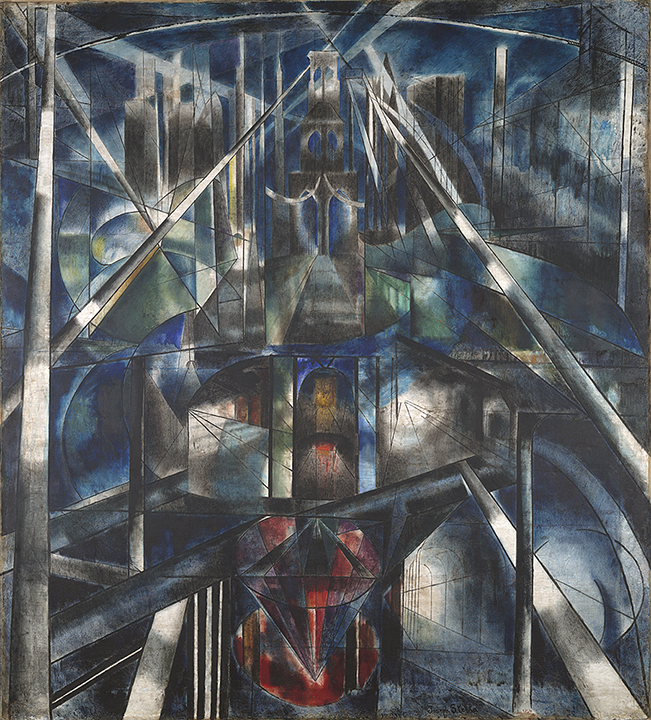

Brooklyn Bridge, 1919–20; Joseph Stella (American, born Italy, 1877–1946); Oil on canvas; 215.3 x 194.6 cm (84 ¾ x 76 ⅝ in.); Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Collection Société Anonyme

The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s, an exhibition examining transatlantic influences in the creation of a broad spectrum of design, reflecting evolving American tastes, from skyscraper furniture to textiles, fashion, jewelry, and accessories, is now open through August 20, 2017. As we explore the changing rhythms of life in the 1920s—with expanded freedoms for women and the cultural impact of African American expressions coming to the fore—we look north to Harlem, where much jazz innovation is rooted, to find out more about the Jazz Age’s origins. Essay by Ryan Maloney.

When you enter The National Jazz Museum in Harlem you are greeted by two pianos—a beautiful, if otherwise conventional-looking, baby grand and a staid, upright player piano. The baby grand is white with lovely hand-carved wooden filigree adorning its sides and music rack, but in truth, if seen outside of a museum, it would be considered simply a piano. The player piano, on the other hand, is a feat of engineering, with dozens of moving parts for each of its eighty-eight keys—it was the first technology that allowed “recorded” music, in the form of a piano roll, to be distributed for in-home enjoyment. By the late 1890s, it brought the ragtime of African American composer Scott Joplin into the American home.

An upright or spinet piano was a fixture in many New York sitting rooms at the turn of the twentieth century. The piano was a point of pride, a place where the family gathered to sing, dance, and entertain. The presence of a piano also promoted music literacy, and piano lessons were considered a rite of passage for children even then. The piano was the tool of innovation for the past, present, and future of music, with Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Liszt, Louis Moreau Gottschalk, Scott Joplin, and eventually Harlemites James P. Johnson, Thomas “Fats” Waller, and later Edward “Duke” Ellington using the instrument to advance their art and share their genius. This progressive spirit was embodied in the title of a 1930 piano opus by Johnson: “You’ve Got to Be Modernistic.”

Kramer baby grand piano belonging to Duke Ellington, on view at The National Jazz Museum in Harlem.

This player piano built by Lauter Pianos in Newark, NJ sits in the “parlor” of the Vibrations exhibition at The National Jazz Museum in Harlem.

The white baby grand piano at The National Jazz Museum in Harlem belonged to Ellington, who used that very instrument as he wrote many of the 1920s compositions that launched his career. He attained the kind of popularity that transcended racial barriers, establishing once and for all that an African American composer and musician could be acknowledged as a peer of not only his contemporaries such as George Gershwin, but also of the nineteenth-century European masters to whom our contemporary orchestras still pay homage.

The player piano, sitting only a few feet from the baby grand, is also significant to Ellington: it represents the technology that allowed the music of Harlem to reach a young Edward Ellington in Washington, DC. The piano roll brought songs emerging from Harlem—such as Johnson’s pièce de résistance “Caroline Shout”—to Ellington and the rest of the country and codified Johnson’s solo jazz piano style, known as Harlem Stride.

This driving solo style became a vital part of the mise-en-scène that enveloped the small, Prohibition-era speakeasies and rent parties (where tenants hosted parties and hired musicians to play so they could pass the hat to raise their monthly rent) that thrived throughout Harlem in the 1920s. Many of the great European composers (Beethoven, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Johannes Brahms) were known as superlative improvisers who not only extemporized at concerts but also informally, for friends at parties. In a way, they were precursors of Johnson’s leading disciple, Fats Waller, who had an extensive classical background and could keep a party going all night with his improvisational flights of genius, synthesizing the varied elements into his next composition.

Textile, ca. 1925; Designed by Lina de Andrada (French, active 1920s); Manufactured by Paul Dumas (Paris, France); Screen-printed cotton; H x W: 102 x 75 cm (40 x 29 ½ in.); Gift of Mrs. Germaine Little; 1968-110-98

WINDING RHYTHMS AND DESIGNS

The innovative African American jazz musicians in Harlem took great joy in combining their own musical discoveries with elements from Africa, Cuba, South America, and Europe. This process helped spawn a new lilting rhythm known as swing, which, as Ellington characteristically put it, “encouraged the terpsichorean urge.”

At dance venues like the Savoy Ballroom—with its marble staircase, mirrored walls, cut-glass chandeliers, and block-long dance floor with bookending bandstands—Harlem musicians were not alone in bending their creations into abstraction and avant-garde thinking. Designers, authors, painters, architects, and socially progressive thinkers gathered at the Savoy and in similar social settings the world over, unencumbered by the segregation of the era, with jazz as the soundtrack. Fashion also underwent a similar infusion of modernity, with the introduction of highly stylized forms of dress; as one elder Harlemite shared with us, “you didn’t go out unless you were dressed to impress.”

It is easy to glamorize this rich period of cultural expression, but it is important to also understand that even in Harlem, segregation and racism were still very much a part of everyday life for African Americans. Though uptown nightlife revolved around nightclubs and speakeasies, most of these establishments were segregated (including the iconic Cotton Club), with only a few integrated venues available, such as the Savoy Ballroom and Smalls Paradise. The impact of the innovations that took place in Harlem in the 1920s are not yet fully understood or accepted as we as a country continue to belatedly acknowledge the full contributions of African American art and culture.

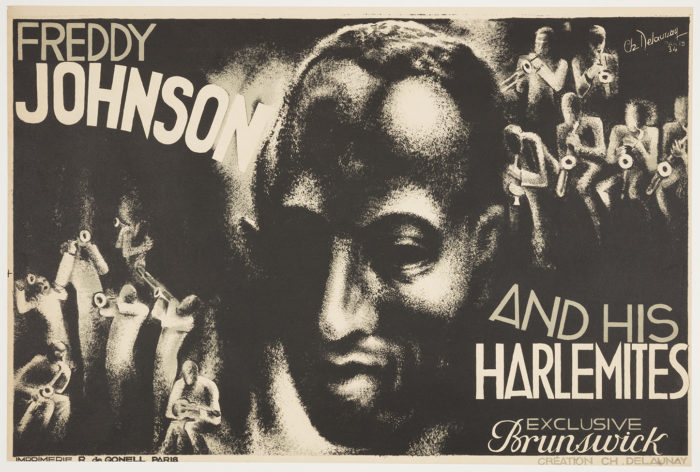

Poster, Freddy Johnson and His Harlemites, 1934; Designed by Charles Delaunay (French, 1911–1988); Printed by Imprimerie R de Gonell (Paris, France); Offset lithograph on paper; 39.8 x 60 cm (15 x 23 ⅝ in.); Promised gift of George R. Kravis II

In the face of this oppression, many African American musicians were drawn to more socially and artistically hospitable cities overseas, with Paris as the hub. The music of black America was already of interest to Parisians, in large part due to the concerts presented in 1918 by the 269th Infantry Regiment “Harlem Hellfighters” band, led by legendary Harlem composer and bandleader James Reese Europe. The music of the Hellfighters was not the same music that we would come to know as jazz in the 1920s, but its syncopated rhythms and ensemble arrangements of ragtime would whet the appetites of Parisians for the sounds of the new African American music emanating from Harlem.

African American musicians in Paris didn’t necessarily find a larger audience or a more financially secure career path, but, compared with life in America and the indignities of touring the segregated South to make a living, the more accepting social climate of Paris was a welcome relief. It comes as no surprise, then, that by the early 1930s the first serious jazz scholarship and criticism emerged in France.

As early as 1919, Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet clearly showed his appreciation of the innovations of African American musicians when writing about a performance in London of Sidney Bechet with Will Marion Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra. Ansermet praised Bechet’s “richness of invention, force of accent, and daring in novelty and the unexpected,” concluding that Bechet’s “own way” is “perhaps the highway the whole world will swing along tomorrow.”

INCUBATING STYLISTIC VIBRATIONS

By the mid-1920s, commercial radio and the popularity of the phonograph began to replace the role of the piano in the home, and this changed the way people accessed music. It was no longer necessary to purchase sheet music, which often included Art Deco and Modernist cover art, to be able to hear your favorite song. You simply purchased a recording to play on your elegant Victor Talking Machine. What was once music that existed only in the ether—largely improvised, heard live, once, and then never the same way again—was now available over the airwaves and reproducible through the grooves of a record.

These developments in technology and industrial design forever altered the significance of the piano in the home. In 1919, 336,000 pianos were sold in the United States—only 130,000 were sold ten years later in 1929. Big bands were filling dance halls with Lindy Hoppers, and jazz reached around the world, initially embraced by the youth and the creative classes, who in many cases were also engaging in the worlds of art and design. Ellington was broadcasting live from the Cotton Club, social mores were being broken left and right, and women were exploring a new social independence with their right to vote, even as the world struggled to deal with the crippling effects of the Great Depression. And, as often has been the case in stressful times, the arts flourished.

The music and design innovations of the 1920s became more fully realized and broadly accepted as we moved into the 1930s. Many have found striking similarities between the streamlined swing of the 1930s and the Art Deco movement that overtook commercial design. The contemporary compositions of Mary Lou Williams, for instance, are aural correlatives to Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films, Buick sedans, and radio consoles of the ’30s. By the end of the decade, the stylistic vibrations that had coalesced in Harlem’s nightspots during the preceding decade had spread around the world.

Muse with Violin Screen (detail), ca. 1929–30; Made by Rose Iron Works, Inc. (Cleveland, Ohio, USA); Designed by Paul Fehér (Hungarian, 1898–1990); Wrought iron, brass, silver and gold plating; 156.20 x 156.20 cm (61 x 61 in.); The Cleveland Museum of Art, On loan from the Rose Iron Works Collections, LLC, 352.1996

Whether in New York or Paris or other major design cities in Europe, the 1920s were a unique time when so many in society—and specifically those in creative pursuits—were able to push, pull, or in many cases break free from the seemingly ironclad traditions of earlier times. While Mary Lou Williams was sitting with Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, Eileen Grey was conceiving her Modernist home, E-1027. While Josephine Baker was transitioning from a star chorus girl on Broadway to Paris—where she attained superstar status as “the most sensational 06woman anyone ever saw” according to Ernest Hemingway—the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs was exposing the world to the style of modern design. The Exposition included the architecture of Le Corbusier and De Stijl; the interior decoration of Jean-Michel Frank; furniture by designers from Jean-Jacques Ruhlmann to Pierre Chareau; Van Cleef & Arpels, Cartier, and Mauboussin jewelry, as well as the more avant-garde Templier; and artists such as Ferdinand Léger and Robert Delaunay.

The shifting of this zeitgeist was driven, in a way, by the two pianos—one, the palette for Ellington’s genius, and the other, a technology that first brought the music of Harlem to the world—that now sit in The National Jazz Museum in Harlem on 129th Street, just east of Lenox Avenue, around the corner from the original locations of so many of the legendary 1920s nightclubs and dance halls. These venues were the incubators, pulsating to the rhythms of jazz, where modern design, dance, fashion, writing, freedom, and style came together to lay the foundation for what we now call the Jazz Age.

This essay by Ryan Maloney is excerpted from the Cooper Hewitt’s Fall 2016 Design Journal, available to Cooper Hewitt members.

Maloney is an archivist, historian, saxophonist, and educator and is the Director of Education and Programming at The National Jazz Museum in Harlem, a Smithsonian Affiliate. He develops and oversees the museum’s collections, exhibits, education programs, and public programs for visitors of all ages.

One thought on “Harlem in the Jazz Age”

Claudia Phelps on May 14, 2017 at 12:15 pm

Wonderful article by a person who really knows his material. The best descriptions I’ve seen in awhile. Has made me plan to visit on my next trip to NYC. Thanks.