Today, the words “asylum” and “sanatorium” conjure mental images of patients in white gowns sitting in cold, sparsely furnished, whitewashed rooms with faded checkerboard linoleum flooring. Knowing the dismal associations with these interiors, it may be surprising to learn that Josef Hoffmann’s textile, Notschrei, was one element of the holistically conceived décor for a sanatorium.

At the turn of the twentieth century, there was a rising interest in psychotherapy and the treatment of individuals with mental illness. In Vienna, Sigmund Freud was one of the influential figures leading dialogues about psychiatric treatment. Cities were perceived as breeding grounds for nervous disorders (which had symptoms that are currently diagnosed as depression, anxiety, and stress), and patients were prescribed retreats into nature to escape the overstimulation and chaos of urban life. It is important to note that during this time there was a clear distinction made between asylums and sanatoriums. Asylums were designated for those with mental illness while sanatoriums treated individuals with nervous conditions. Unlike asylums, commitment to a sanatorium was usually voluntary.[1] Most patients did not choose to go to an asylum or have a say about which asylum they were assigned to. Asylum interiors were Spartan and sterile, often reflecting their status as public institutions. Conversely, some sanatoriums, such as the Purkersdorf Sanatorium, located outside of Vienna, were more like luxury hotels than medical facilities. Purkersdorf, a private institution, was a retreat for the urban elite to recuperate from the stresses of the city.

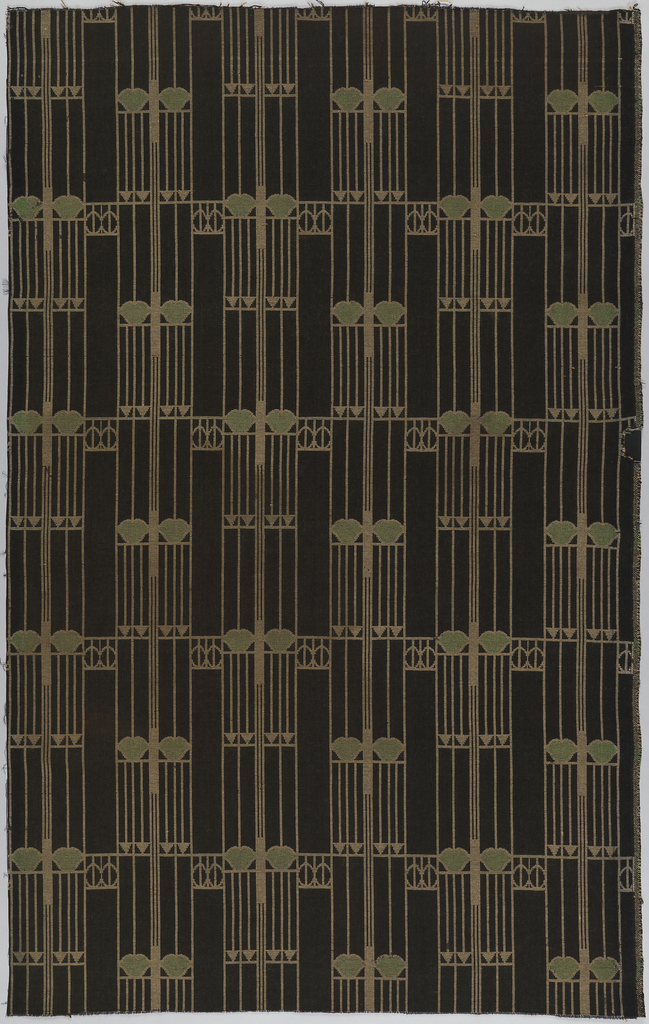

From 1903-1904, Josef Hoffmann designed a new building for the Purkersdorf Sanatorium, which was established in 1890. From the architectural plan to the furniture inside, Hoffmann focused on creating a soothing atmosphere. The textile Notschrei references its place of use only by its name, which translates to “cry for help.” The geometric and linear pattern accurately reflects Hoffmann’s style and speaks to his belief that one's environment could inspire change. He intentionally used geometric and linear elements throughout the building to create a calming atmosphere. In addition to providing a palliative experience, it was important that sanatoriums for middle class and elite patients not reflect or have any direct connotations of mental illness. A beautifully decorated facility cloaked the stigma associated with sterile institutions for the mentally ill.[2] Hoffmann’s Notschrei is a unique decorative element for a medical building. With nervous conditions, there is no fear of spreading disease or infecting other patients, allowing for the use of woven textiles and upholstered furniture. In a tuberculosis hospital, textiles would have been replaced with wood or another easily sanitized material. Hoffmann’s involvement in the design of Purkersdorf illustrates how psychiatry was piquing the interest of artists and designers during this period.

Read more about Josef Hoffmann’s Purkersdorf:

Visual Arts in Vienna 1900. Surrey, England: Lund Humphries, 2009.

Martin, Colin. “Exhibition Review: Secession to Sanity.” World Health Design.

http://www.worldhealthdesign.com/Exhibition-review-Secession-to-sanity.aspx

Megan Elevado is a Brooklyn native who is fascinated by East German and Soviet culture and design. She earned her BA at New York University and completed her MA in the History of Decorative Arts and Design at Parsons The New School for Design in May, 2013.

[1] Nicola Imrie and Leslie Elizabeth Topp, Madness and Modernity: Mental Illness and the Visual Arts in Vienna 1900, (Surrey, England: Lund Humphries, 2009), 87.

[2] Ibid., 88.

One thought on “Josef Hoffmann’s Notschrei”

Gogi on January 18, 2021 at 3:44 pm

ca you tell me the dimensions of the Notschrei piece that you have? Also, any idea if this piece was used at the sanatorium or if this pattern was used in other places?