Among the most influential books in the history of American graphic design is Paul Rand’s Thoughts on Design, published in 1947. Covering the jacket of this ground-breaking manifesto of modernist theory and practice is a series of oblong dots arranged in uneven rows, rendered in translucent shades of gray. The image is based on a photogram, made by exposing a wood-and-wire abacus to a sheet of photographic paper. At once abstract and recognizable, the photogram is a direct imprint of a physical object.

Cover of Thoughts on Design by Paul Rand. Published by Wittenborn and Company, 1947. Smithsonian Libraries. NC997 .R3X

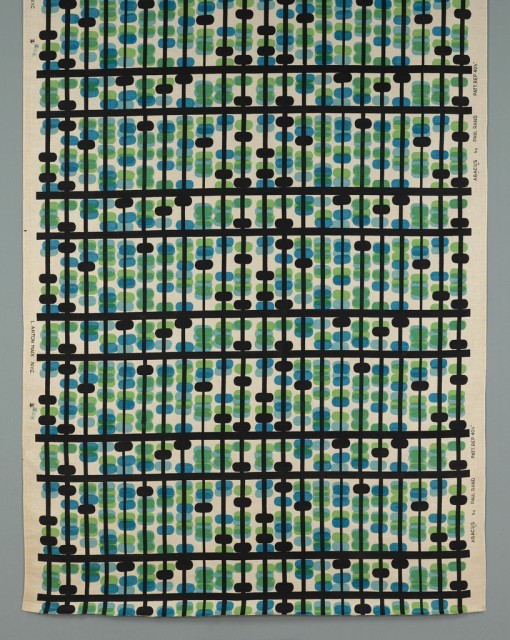

Rand used his photogram as the basis of a pattern design as well as for the cover of his famous book. Working with the progressive manufacturer, L. Anton Maix in New York City, he created Abacus around 1946. The play between dark and light, foreground and background, transparency and opacity, endows this simple printed textile with movement and depth, while the pattern’s ordered columns gracefully follow the folds of the fabric.

L. Anton Maix produced screen-printed fabrics by many progressive designers of the day, including graphic designer Alvin Lustig, furniture designer Paul McCobb, and architects Erik Nitsche and Serge Chermayeff. Such works represented a new ethos in pattern design in the 40s and 50s, when artists and designers were devising whimsical patterns based on iconic depictions of anything from toys, birds, and flora to numbers, letters, and geometrical figures. Such patterns took inspiration from the biomorphic paintings and organic furnishings of the era. Abacus and other progressive textiles appeared in MoMA’s 1951 exhibition, Good Design, which celebrated high-quality products in current production. The catalog included retail prices of the products on view—Abacus sold for $6.75 per yard, a cost in line with other textiles in the exhibition, which ranged from around $3 to $20 a yard.

Rand, building on the revolutionary ideas of the prewar avant-garde in a practical and matter-of-fact manner, forged new connections between art and business. He went on to create corporate identities for companies such as IBM, Westinghouse, UPS, and—towards the end of his life—Enron. Just as he built Abacus from a simple and evocative image, Rand devised unforgettable logotypes and corporate symbols by simplifying and distilling core ideas. In Thoughts on Design, he wrote,

“The designer’s capacity to contribute to the effectiveness of the symbol’s basic meaning by interpretation, addition, subtraction, juxtaposition, alteration, adjustment, association, intensification, and clarification, is parallel to those qualities which we call ‘original.’” Rand, best known for his work in advertising and identity design, participated as well in the broader dissemination of graphics in the domestic environment. He did so in a way that was always crisp, bold, and original.