Proudly displaying his royal, albeit long-embattled standing, Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619-1682) placed a crown on his initials in the top right corner of his 1662 mezzotint, Head of the Executioner. Besides his impressive lineage, the Prince is also credited with revolutionizing the mezzotint printing process.

Mezzotint is a printing method in which the printing plate is uniformly scratched with little pricks. With the simple application of ink to the pricked plate, the resulting image is fuzzy and black; therefore, to create lighter tones in the printed image, one must scrape away the pricks. Total removal of the pricks results in white space, while partial scraping creates the rich gradient that you see, for example, in the cloth wrapped around the Executioner’s head. [1]

Prince Rupert met the inventor of mezzotint—Ludwig von Siegen—while in exile, and developed a tool called a “rocker,” a curved saw edge that easily and effectively roughens the mezzotint printing plate to give it its initial dark tone.[2] In 1660, the Prince brought his optimized mezzotint technique to the court of his cousin, Charles II of England, where it gained popularity. In 1662 the English writer John Evelyn published the artist’s Head of the Executioner as an example of the mezzotint technique. [3]

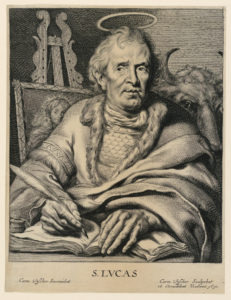

Inexpensive and relatively quick to produce, mezzotints became an acceptable alternative to proper paintings because the soft tonal gradient mimicked the blending power of paint, and in fact, Rupert’s print reproduces part of a painting. [4] Earlier printmaking methods such as engraving—in which the printmaker creates tidy networks of line to create tone—could rarely achieve such painterly effects, as seen in this Dutch engraving by Cornelis Visscher produced a decade before Rupert’s invention (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Cornelis Visscher, St. Luke, 1650. Engraving on off-white laid paper. Bequest of George Campbell Cooper. 1896-3-207.

Mezzotint became so popular in England that it came to be referred to as the “English manner” of printmaking.[5] In the early 19th century, Joseph Mallord William Turner, perhaps the most famous English painter, published a series of prints including Cooper Hewitt’s view of Morpeth, Northumberland (fig. 3), which combined etching—also considered the painter’s printmaking medium—with mezzotint in order to capture the airy, luminous landscape views that Turner had achieved to great acclaim in paint. Prince Rupert’s innovations in the mezzotint process were a critical part in enriching the potential of the print medium.

Fig. 3. Turner and Charles Turner, Morpeth, Northumberland, from the Liber Studiorum, 1809. 1957-191-3.

[1] A. Hyatt Mayor, Prints & People: a social history of printed pictures (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971). Web. Accessed April 30, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=YQzsKZmz9m8C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=rupert&f=false

[2] For an example of another Prince Rupert mezzotint and additional information see “The Great Executioner with the Head of Saint John the Baptist,” Metropolitan Museum of Art. Web. Accessed April 30, 2017. http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/671399?sortBy=Relevance&ft=prince+rupert&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=1.

[3]Op. cit., note 1.

[4] Anthony Griffiths, The Print Before Photography: An Introduction to European Printmaking 1550-1820 (London: British Museum, 2016), p. 74.

[5] Ibid, p. 484.

Alec Aldrich is the 2017 IFPDA Graduate Curatorial Fellow in Prints and Drawings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. He specializes in seventeenth-century Dutch art, the focus of his graduate studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

One thought on “Off His Rocker: Prince Rupert and the Mezzotint”

Maria La Place on May 29, 2017 at 1:20 pm

Is there some reason why the Turner print image is so tiny? One can hardly see it.