Excerpt from Theodore Jojola’s essay “The People are Beautiful Already: Indigenous Design and Planning” from By the People: Designing a Better America exhibition publication.

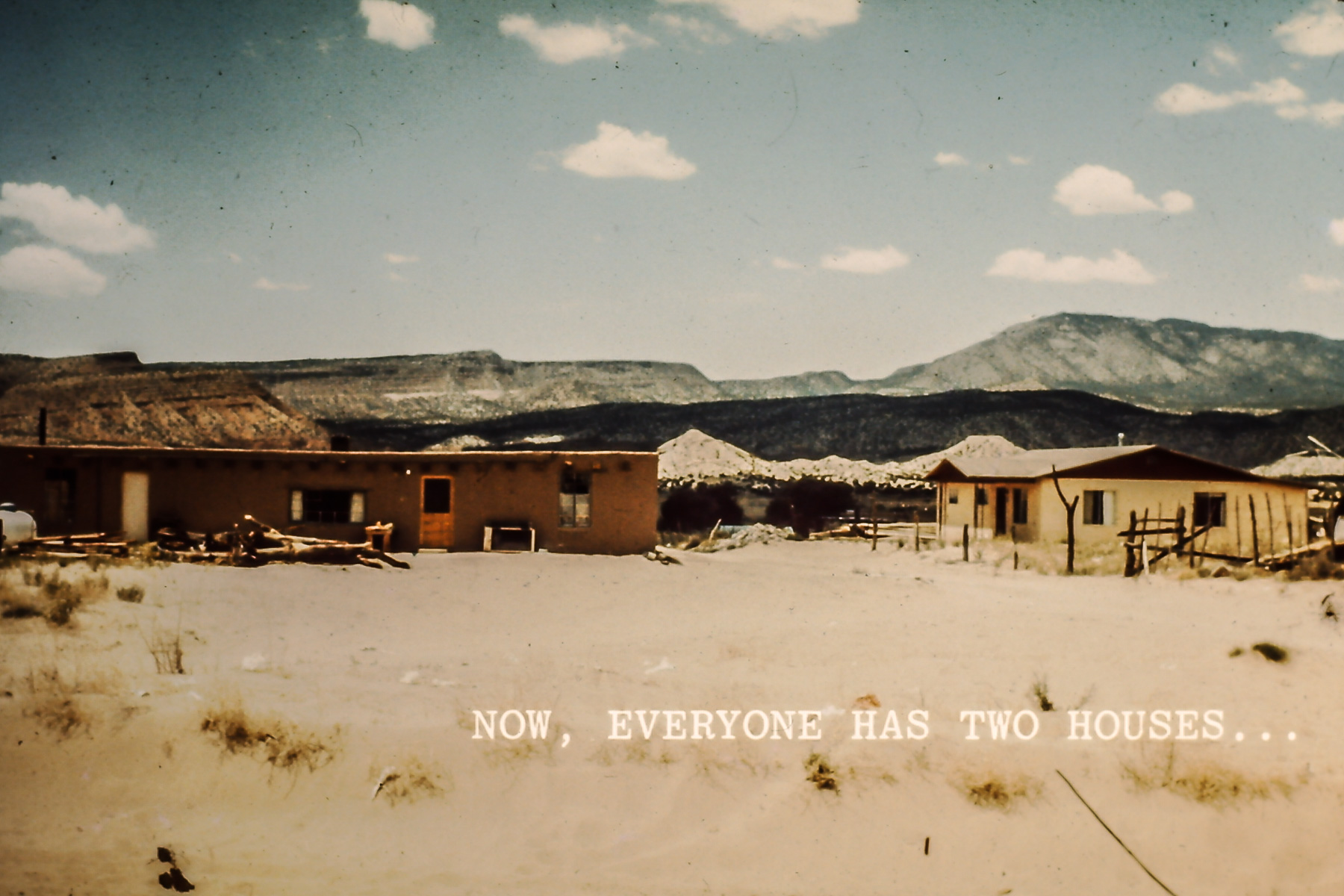

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) program was intended to replace “substandard” traditional housing. Many families opted to build their new HUD housing next to their original homes. A federal HUD house (right) sits adjacent to an adobe house.

Theodore Jojola, PhD, is Director, Distinguished Professor, and Regents Professor, Indigenous Design + Planning Institute (iD+Pi), School of Architecture + Planning (SAAP), University of New Mexico (UNM), and was cofounder of the Indigenous Planning Division of the American Planning Association. He is an enrolled tribal member of the Pueblo of Isleta.

Indigenous Design

Indigenous design often goes hand in hand with the evolution of architectural practice. As members of their respective communities, practitioners adhere to social protocols and are aware of their place in the culture. They are attuned to the spirituality, language, and landscape of the places they represent. Their role as architect is that of facilitator. The process of design is not driven by artistic and heuristic imperatives. Rather, it is an orchestration of public engagement that gives voice and clarity in the built form. Over time, Indigenous design practitioners began to advance their professional credentials and empower their communities to design and plan for culturally relevant “good buildings.”[1]

Indigenous design is not vernacular architecture. Historically, Indigenous architecture has been dismissed as inconsequential to the evolution of “great” building traditions in the Americas. Often relegated to anthropology and the study of quaint vernacular traditions, Indigenous architecture, as a result, has been consigned to anonymity and obscurity, frozen in time.

On the other hand, Indigenous design strives to be more than the sum of its parts. Whereas mainstream architecture tends to evaluate buildings on elements such as style, function, and form, the measure of Indigenous form is around its cultural meaning. It is the embodiment of practices and principles that are informed by the culture of the community.

Contemporary practices of Indigenous design are distinct and unique from the general practice of architecture because of its regenerative purpose. Buildings become the narrative of a community. The building becomes a metaphor for stories that are invested in place and time as seen on the previous page.

As a professional, the architect as designer manifests design solutions that are culturally appropriate and that use new and old technologies to make buildings sustainable. They are also invested in materiality and the conservation of local resources. Elements of a building’s design, including its site, structure, spaces, lighting, doors, windows, and colors, as well as countless haptic material details, expand its dimensionality.

All of the processes, designations, symbols, and meanings represented by indigenous architects are the primal elements of a cultural toolbox. These are not taught in the Euro-Western architecture tradition; they are learned and inherited through the culture. For example, Indigenous motifs are neither random nor simply decorative. Instead, they relate to cultural symbols that are integral to representing and depicting the worldview of Indigenous people. Some of the basic design elements are shared by many Indigenous communities and become necessary for making buildings suitable for their usage and cultural acceptance.

Entrances that are oriented to the east—the direction of renewal or birth—may pay homage to the spiritual renewal as symbolized by the rising sun. As the sun ascends and descends to the west, the movement symbolizes the cycle of life. West is the direction of the afterworld. The site orientation of a building may further denote the seven access points of sacred geography, which include the four major cardinal directions, a zenith, a nadir, and a center point. A center point may allude to the earth-navel, or emergence point of humankind. The directions may be specific colors and relate to totems.

The narrative of Indigenous design is replete with references to spiritual and cultural forces that are more profound than any individual’s single intervention. These spiritual forces represent a blueprint for design. They shape the land and the communities that they sustain. The spaces that are created harbor the custodians to human advancement. The political, social, and economic dimensions of the community help to define the physical development of a place. Indigenous design focuses on how a community can prosper alongside the traditions and values of its people in a manner that allows them to cope and adapt to the outside influences that challenge them.

Indigenous Planning

Lessons witnessed in Indigenous design are also applicable to the larger embodiment of Indigenous planning. Indigenous planning is an emerging paradigm that uses a culturally responsive and value-based approach to community development. Some of these values are inherent in the worldview of the community. The juxtaposition of the sacred directions and landmarks, metaphorical representations of their emergence stories, and nuanced elements of the traditional language are integral to the cultural representation of community. Other values are attendant to land tenure. Of these, the most fundamental is the right of inheritance, which obligates an individual to protect and pass on what they have inherited at birth onto their children. This is the essence of sustainability.

For too long, Indigenous communities have been subjected to what has been characterized as “attemptive planning.” Top-down or outsider solutions imposed by federal funders have edged out localized practices that represent community-engaged planning. These outside impositions have resulted in start-and-stop development that has disrupted the holistic flow of placemaking. And although solutions to protect Indigenous communities have focused on language preservation, environmental protection, economic development, and public health, only recently has the role of planning been recognized as an instrument for positive community change.

Beginning in the early 1990s, students of color in urban studies were beginning to question the relevance of contemporary practices for their rural and urban minority populations.[2] Their discussions were influenced by the 1993 United Nations pronouncement on the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Key to its implementation was an articulation of the need by countries to consult and cooperate with Indigenous people by providing financial support for strategic planning in areas pertaining to human rights, the environment, development, education, and health.

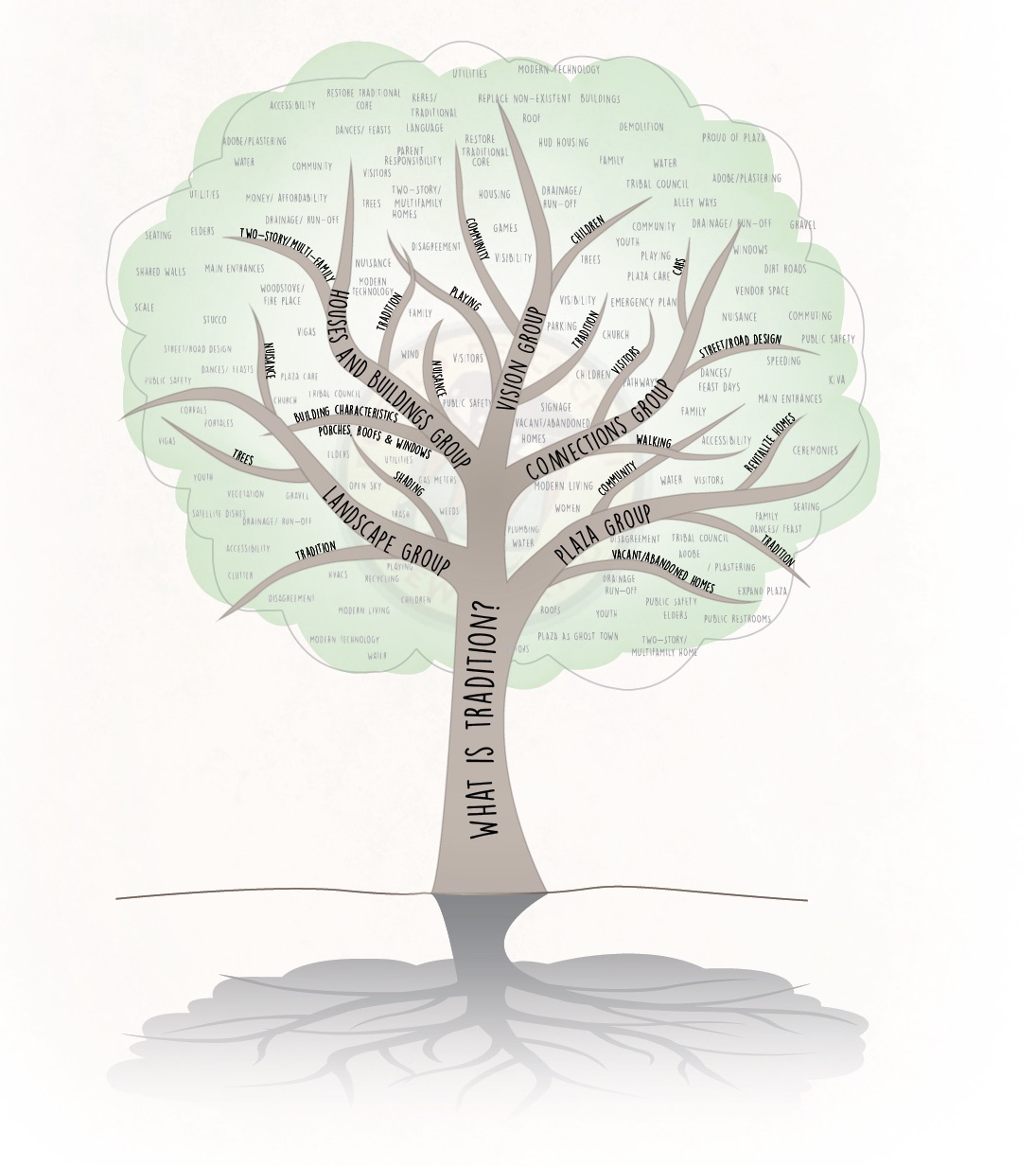

The image is a metaphorical reference to trees that once grew in the plaza of Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico. Community groups engaged in a number of discussions (major branches) on the central theme, “What is Tradition” (tree trunk). Word clouds were generated from the summaries (minor branches and canopy). Cochiti Pueblo Plaza Revitalization Plan, iD+Pi, 2014.

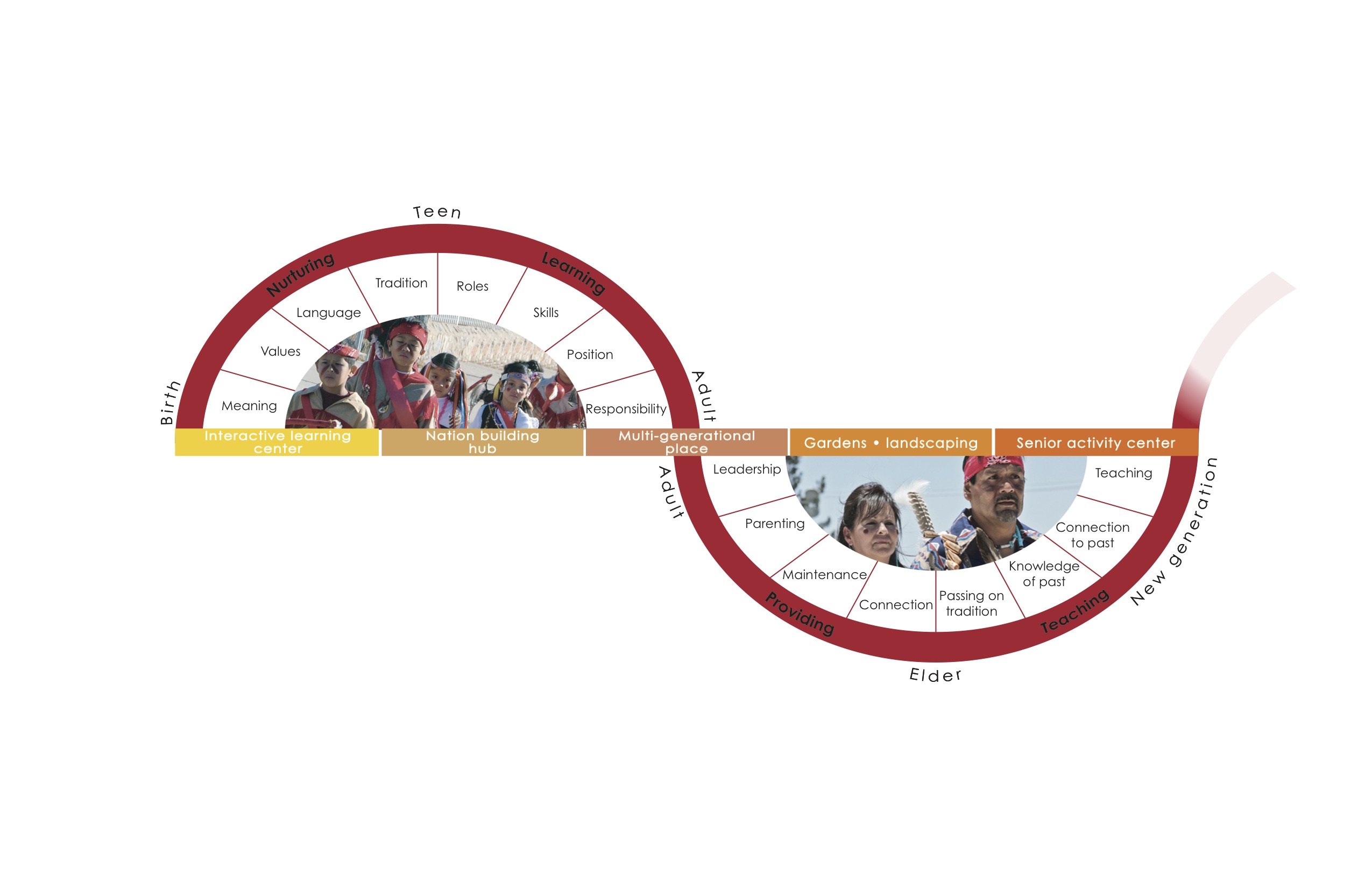

Indigenous planning is a participatory process predicated on establishing a set of principles that are informed by generations that are ever-present in a healthy community. A seven-generation planning model connects the past, present, and future through the older generations (great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents), the mid-generation (self), and the younger generations (children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren).

The seven generations model assesses how communities sustain patterns of intergenerational interplay through the lifetime of an individual. As the lifecycle of individuals moves from infancy through elderhood, they learn values and mature into their requisite roles and responsibilities. Community institutions are invested in making sure that this occurs in an orderly and timely fashion.

A worldview represents the community’s understanding of itself and its relationship to the natural world that sustains it. Newborns are ushered into a nurturing culture that accords them associated rights and restraints to land. It is not a property right. It is negotiated through consent. In practice, land is communal and is beholden to a right of commons. Socio-cultural interests, such as those of the tribe’s moieties and clans, may dominate. The family becomes the basic operational unit. In sum, however, it is the collective right of the whole that propels the community into the future.

Seven Generations Model for Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo, Texas. The red line depicts the life cycle of an individual and the associated values they learn as they mature through adulthood. The horizontal timeline identifies the institutions in the Pueblo that support each stage of an individual’s life. Ysleta Cultural Corridor Plan, iD+Pi, 2012.

The People are Beautiful Already

The Indigenous Design and Planning Institute (iD+Pi) at the University of New Mexico was established on the belief that Indigenous communities should benefit from the best practices that design and planning have to offer but in a manner that is culturally informed. We are part of an international movement that has representation in Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, and in various Latin American countries such as Mexico, Ecuador, and Peru—countries where significant concentrations of Indigenous people reside in identifiable territories.

At its core, Indigenous design and planning entails three interrelated sets of activities.

The first is education. Workshops explain key concepts, engaging stakeholders in a shared discussion about the context behind demographic and land-use change. The conversations clarify and build consensus around enduring cultural values that are necessary to guide the growth and evolution of the community.

The second activity is community engagement. We work with local leadership to identify key individuals who can meaningfully contribute to conversations about place. This entails understanding cultural protocols, local history, identifying and using existing social networks, and nurturing a working relationship among program and community liaisons to organize community meetings. Community-engaged methods, such as participatory asset mapping, are deployed to gather information and expand the conversation across the generational spectrum.

Summary reports are developed and findings are disseminated to the community for further discussion and refinement. Oftentimes, this requires conducting dozens of meetings over the course of the project in order to facilitate a reflective dialogue and build consensus.

The third activity is transcriptive. It entails an interdisciplinary team of faculty, students, and professionals assisting the community to produce materials, including records, assessments, chronologies, and narratives. The collaborative process transforms the community’s ideas through visual designs and conceptual planning documents. These community-driven documents are integrated into a professional portfolio that can be shared and used to leverage resources and funding.

In summary, the Indigenous planning process requires that leadership balance the immediacy of action (short term) with a comprehensive vision (long term). Community engagement and meaningful public participation is the key to its success. Indigenous designers and planning practitioners give voice to the community. They are facilitators, not imposers of authoritative solutions. They inspire and work toward improving the quality of life for its constituents. They are obligated to see through a course of action or, at the very least, assist the community to build local capacity. Ultimately, they heal deep cultural wounds by assisting the community to reclaim its culture and heritage.

The exhibition By the People: Designing a Better America is on view now through February 26, 2017.

Footnotes

[1] Joy Monice Malnar and Frank Vodvarka, New Architecture on Indigenous Lands (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

[2] Ted Jojola, “Indigenous Planning and Resource Management,” in Trusteeship in Change: Toward Tribal Autonomy in Resource Management, ed. Richmond L. Clow and Imre Sutton (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2001).

4 thoughts on “The People are Beautiful Already: Indigenous Design and Planning”

John Cooper on July 19, 2021 at 6:54 am

nice article, thanks for sharing! https://www.cooperhewitt.org/

Forest on August 27, 2021 at 3:53 am

I think this picture is sutable for many countries

mustafa al dory on December 1, 2022 at 4:05 pm

that is a great article ,it is not only in america but also in whole world , ancient and indigenous people have some secret’s in designing we still do not know ,but we have the chance to learn from them ,beside keeping the culture growing

Tehmina Mehmood on March 26, 2023 at 4:28 pm

thank you so much for enlightening on this particular subject this article is very easy to comprehend as I needed to get a proper understanding on indigenous architecture.