In 1767 the French writer and critic, Denis Diderot expounded the ”poetics of ruins” writing, “a palace must be in ruins to evoke any interest.”[1] Diderot’s comments were directed toward paintings by the French artist Hubert Robert that often featured real and fantastical Italianate ruins. Such vogue for ruin paintings were inspired by sites frequented by pensionnaires (French artists studying in Rome).

Of these, a popular spot was Hadrian’s Villa (Villa Adriana), a Roman Villa built near Tivoli in 118-134 CE. The complex included some sixty distinct buildings, numerous fountains, and elaborate waterworks. In the etching above, the eighteenth-century Roman architect and designer Giovanni Battista Piranesi depicts the apse of the Hall of the Philosophers (Sala dei Filosofi) and the wall of the Praetorian fort. (Pretorio) The Philosopher’s Hall dates to 118-125 CE and was originally executed in porphyry. It likely served as a reception hall for imperial audiences and meetings. Piranesi’s print comes from a volume titled Le Vedute di Roma, a collection of etchings of different views of Rome. In this sheet, Piranesi exaggerates the architectural proportions and emphasizes grandeur of this dilapidated site through dramatic contrasts of light. The idling figures, the architectural fragments, and the profusion of vegetation together emphasize the passage of time. Some of the figures gesture to the ruins, lest the viewer’s eyes wander away.

Emperor Hadrian intended the villa as a type of a microcosm of the Roman Empire with some of the buildings were named after famous landmarks in Athens. Extensive excavations of Hadrian’s Villa began in early sixteenth century under Pope Alexander VI. Around 1550s, the architect Pirro Ligorio continued the excavations and appropriated art works from the villa to furnish the famed Villa d’Este that he was constructing for Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, the nephew of Pope Alexander VI. Even from the Renaissance, artists and architects such as Raphael and Bramante drew inspiration from Hadrian’s Villa. Later, architects such as Andrea Palladio and Philibert de l’Orme included detailed and measured studies of Hadrian’s Villa in their respective architectural treatises.

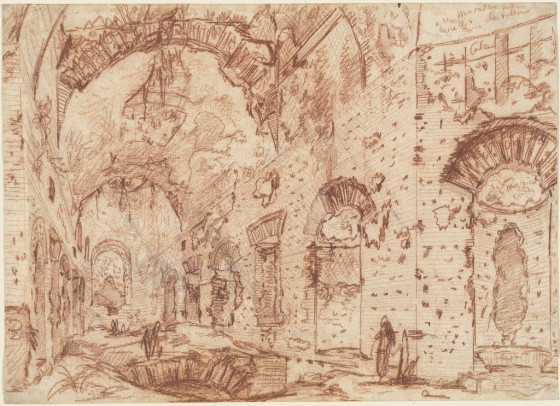

Piranesi, too, was captivated by the Villa, and made several expeditions to the site from the 1740s, occasionally accompanied by Robert Adam and Charles-Louis Clérisseau. Piranesi thus created many drawings and etchings after the site—the Vedute di Roma contains ten different views of Hadrian’s Villa! Piranesi additionally drew up a detailed site plan, which was published by his son Francesco Piranesi. The etching and an animated red chalk drawing by Piranesi featured below depict the “Canopus” of Hadrian’s Villa, which was inspired by the ancient Egyptian city of Canopus and Alexandria.

Print, Interno del Tempio do di Canopo nella Villa Adriana from Le Vedute di Roma, 1776, Designed by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Etching, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Inv. no. R8392.

Drawing, The “Canopus” of the Villa Adriana at Tivoli, 1776, Designed by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Red chalk over black chalk on heavy laid paper, 38.9 × 53.8 cm, National Gallery of Art, D.C., Gift of Ladislaus and Beatrix von Hoffmann, Inv. No. 1994.69.1

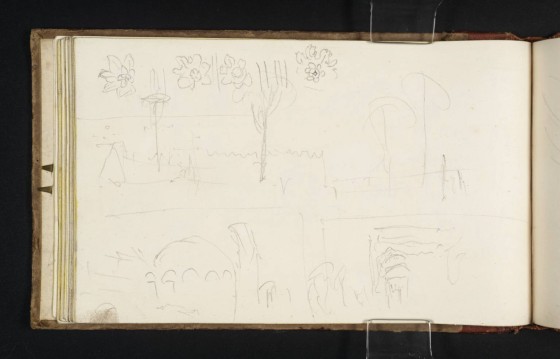

Following Piranesi, a long list of artists including Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Hubert Robert, Charles de Wailly and Marie-Joseph Peyre sketched and mapped out Hadrian’s Villa. A drawing of the Philosopher’s Hall can also be found in the lower left corner of Joseph Mallord William Turner’s Tivoli to Rome Sketchbook, seen below.

Drawing, Sketches of the Villa Adriana, Tivoli: the Hall of the Philosophers and Poikile Stoa, from Tivoli to Rome Sketchbook, 1819; Drawn by Joseph Mallord William Turner, Graphite on paper, 11.2 x 18.6 cm, Tate Britain, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856, Inv. no. D14989

More recently, Le Corbusier visited Hadrian’s Villa in 1911 and his sketches after it can be found in his Voyage en Orient sketchbook. Le Corbusier would later incorporate some of these sketches in his published discourses on architecture. He was particularly inspired by the lighting system at the Serapeum (near Canopus).

Hadrian’s Villa has been a UNESCO Heritage site since 1999 and is available for visits. The twenty-first century reality of the site is far from Piranesi’s grandiose visions. Still, Piranesi rendering of Villa Adriana seem aligned with Denis Diderot’s call on ruins that “the ideas ruins evoke in me are grand. Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes, everything passes, only the world remains, only time endures.”[2]

Cabelle Ahn was formerly an MA fellow in the Department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She is currently a Ph.D candidate at Harvard University, focusing on eighteenth-century French drawings.