2000 National Design Award Winners

Celebrate design

The National Design Awards program celebrates design as a vital humanistic tool in shaping the world, and seeks to increase national awareness of design by educating the public and promoting excellence, innovation, and lasting achievement.

Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry is known for making astonishing buildings, but his achievement is much greater: he has single-handedly made design a public event. Cities clamor for his buildings, and people make pilgrimages to their doorsteps. In 1962, he formed Frank O. Gehry & Associates in Santa Monica, California, and in 1978 he gained widespread public attention for the reinvention of a humble bungalow for his family. His titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, in Balboa, Spain (1997) has transformed the museum and the city. Other projects include Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, a computer science center at MIT, and Vitra Design Museum in Germany. Since winning the Lifetime Achievement Award, he has taken on increasingly complex projects, including designs for a proposed Guggenheim Museum in New York City and a new wing at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

AMERICAN ORIGINALS

This honor—created especially for the first National Design Awards—is bestowed on individuals who have achieved the feat of becoming cultural icons by taking highly personal, even iconoclastic, paths to hone a unique vision of design.

Morris Lapidus, 1902-2001

Morris Lapidus studied acting at New York University and architecture at Columbia University before embarking on one of the most dramatic careers in the history of American architecture. Today the architect is best known for his design of two of the most glamorous postwar resort hotels in Miami Beach, the Fontainebleau (1954) and the Eden Roc (1955); for inventing the modern storefront; and for a large body of work that includes office buildings, apartment complexes, stores, hotels, and stage sets. It is hard to believe that Lapidus was once dismissed for his stylistic excesses. Today his joyful subversion of European modernism through a uniquely American vernacular of entertainment, spectacle, and whimsy is admired and studied by a new generation of architects. An American original, Morris Lapidus has turned Vitruvius’s trinity of classical architectural principles—commodity, firmness, and delight—on its head, putting delight at the apex of the experience of architecture.

AMERICAN ORIGINALS

This honor—created especially for the first National Design Awards—is bestowed on individuals who have achieved the feat of becoming cultural icons by taking highly personal, even iconoclastic, paths to hone a unique vision of design.

John Hejduk, 1929-2000

True romantics are dangerously scarce these days. Thus the death of architect John Hejduk this past 2000 was a loss of devastating proportion. He was his profession’s poet. Hejduk transformed a traditional practice into an intellectual and spiritual voyage that investigated architecture as the expression of ideas—ideas about the human conditions of personal relationships, community, and rites of passage from birth to death. In effect, he created an architecture of the soul. An American original, he forcefully crossed mediums and presaged the current developments in virtual architecture. As Dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art for twenty-five years beginning in 1975, he influenced generations of architects with his passion and deeply imprinted them with his vision. Through his lifelong investigations, Hejduk, ever the transcendental pragmatist, illuminated new corridors of thought and practice.

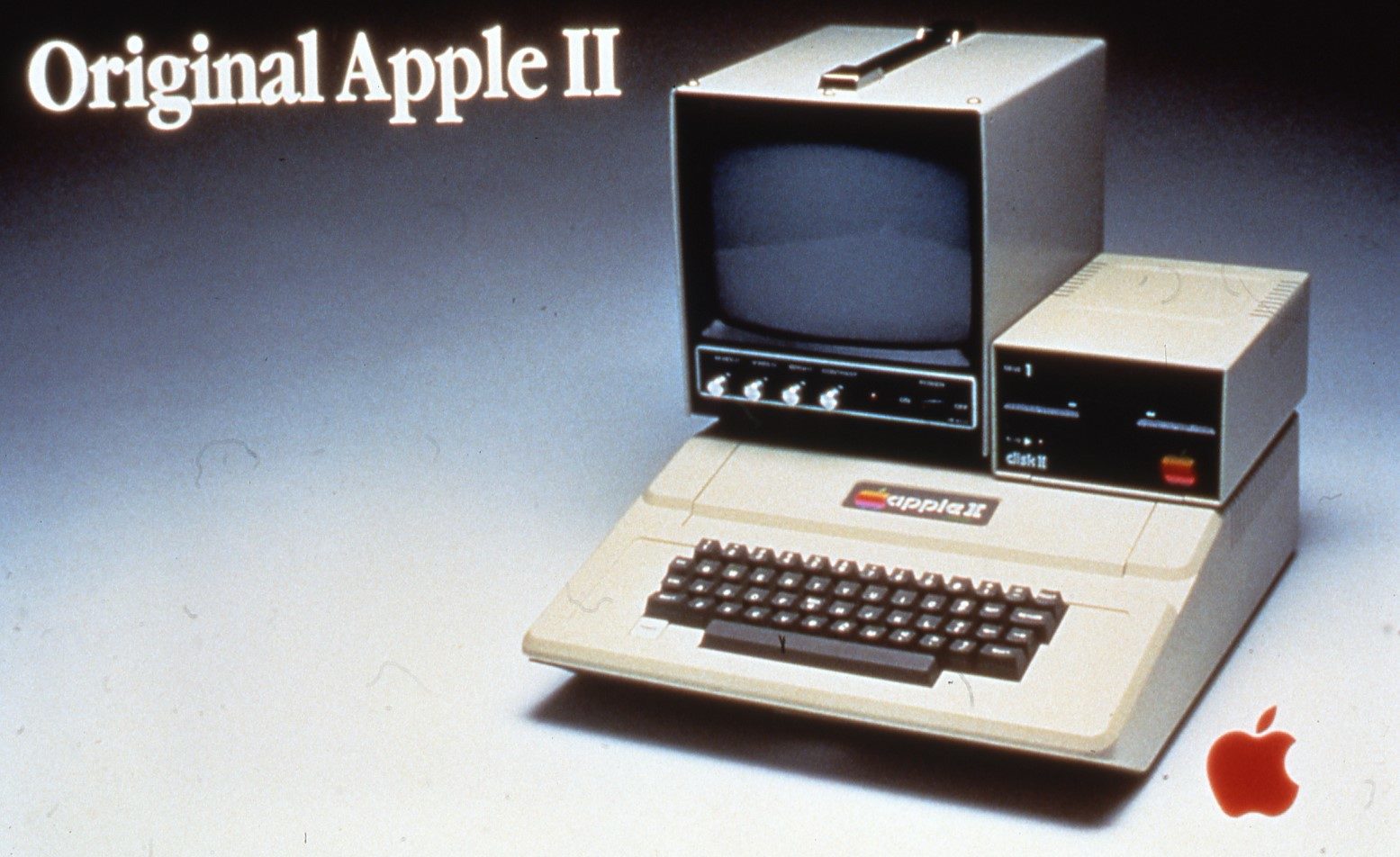

Apple

When Apple rolled out its new iMac in 1998, commentators couldn’t resist hailing the colorful new computers as the fruits of a design revolution. However, this was no conversion: the iMac was an affirmation of Apple’s core values. Since the mid-1970s, Apple Computers has overturned industry standards of speed and functionality with an approach that values design as an integral part of computer engineering. Apple’s first personal computer, the Macintosh, hit the market in 1984, introducing human-centered, easy-to-use applications, “icons,” and the point-and-click mouse at a time when other personal computers required technical expertise. Today, a reinvigorated Apple produces such leading products as the Power Mac G4, PowerBook G4, iPod, iBook, and the company continues to be one of the major suppliers of personal computers to schools and universities. Apple’s new flat-screen iMac, released in 2002, reaffirms the company’s devotion to design as a central tenet of their business plan.

Ralph Appelbaum

When Ralph Appelbaum began his career three decades ago, designing an exhibition might have meant little more than specifying wall color and pedestal dimensions. Today, the museum designer creates exhibitions that rival movie sets in technical complexity and books in narrative intensity. Appelbaum’s designs have transformed museums from temples into public forums. For each project, he assembles a cast of architects, model makers, historians, and childhood specialists—as well as poets and scientists. The diversity of talent on his teams underscores Appelbaum’s conviction that communication is a holistic enterprise, involving all three dimensions and all five senses. Appelbaum has honed the exhibition into one of the most persuasive and pleasurable means of communicating knowledge. His important projects include the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., the Museum of African American History in Detroit, and various exhibition halls at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Lawrence Halprin

Since opening his San Francisco design office in 1949, Lawrence Halprin has been in the business of bringing gardens—and their attending civic graces—to American cities. Remarkably, he romanticizes neither. In fact, the key to Halprin’s success may lie in his acceptance of the reality of his materials—natural forms that grow, change, and simply don’t stay put—and of the people whose lives are affected by his work. The central role of human movement in his landscapes is evident in one of his best-known projects, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, D.C., which Halprin describes as a “walking environmental experience.” One of the first landscape architects to address landscapes damaged by urban freeways, Halprin’s Seattle Freeway Park and the Westchester Wall have become prototypes for integrating highways into communities. Other important projects include Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco and an overlook to the Old City of Jerusalem.

Paul Maccready

Design today places a premium on beauty, lightness, speed, and sustainability. Paul MacCready’s energy-efficient vehicles have been a paragon of those virtues for decades before they became so urgently fashionable. MacCready’s early innovations earned him the moniker “father of human-powered flight.” In 1977, MacCready made history with his Gossamer Condor, the first successful human-powered airplane. Two years later his Gossamer Albatross broke records as the first human-powered aircraft to cross the English Channel. Supported by NASA, MacCready and his team are currently at work on solar-powered high-altitude aircraft that will someday allow for nonpolluting flights in the stratosphere and the relaying of multichannel-bandwidth communications. Committed to the green evolution of all modes of human transport, he is also deeply engaged in experimentation with new solar- and electric-powered cars and is a leader in global initiatives to develop vehicles powered by batteries and alternative fuels.