The huge figures dominating the composition of this Soviet poster stand as grotesque monuments to Russia’s imperial past. Labeled pedestals identify them as priest, tsar, and bourgeoisie—all cruel oppressors in the eyes of the new regime. Their rough-hewn faces crudely caricature the elegant, ostentatious sculptures of past tsars, and they tower over two naturalistically rendered everymen. Undaunted, these men reject the authority of the rulers, and set fire to them. Above them, text proclaims “On the Eve of the World Revolution.” Like many other posters designed in 1920, this anonymous work commemorates the third anniversary of the Russian Revolution. That year, the state press produced more than four times the number of posters printed in 1919. This aggressive print campaign intended to reactivate public patriotism. As White Guardsmen and invading Poles threatened to destabilize the Bolshevik leadership, posters like this one intended to revive faith in the Party cause, and remind viewers of their common enemy.

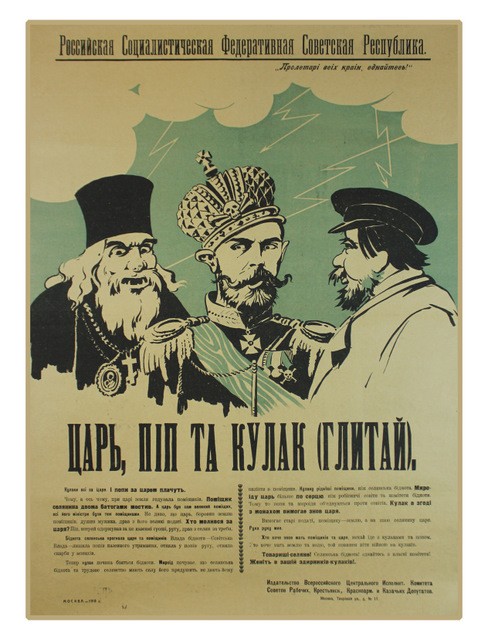

The enemies in this poster are not specific individuals, but ideological symbols, identifiable only by attributes like a bag of rubles or a royal crown. Just as the designer abstracts specific people into social categories, he deconstructs their bodies into fundamental shapes. The strategy reflects a mainstream embrace of visual abstraction, itself a recent development. This poster’s menacing lineup of priest, tsar, and bourgeoisie adapts an established motif, first depicted in 1918, in one of the first Soviet posters (Figure 1). A priest, tsar, and kulak, or wealthy farmer,appear in the earlier poster, depicted with similar distaste. The slack-jawed tsar sports a skull-and-crossbones crown, the priest bares sharp fangs, and the fat kulak admires them slavishly. The trio was villainized in many subsequent posters, though the manner of their representation evolved to suit artistic trends. Their portraits grew increasingly simplified, such that in On the Eve of the World Revolution, they barely resemble the 1918 group. While the tsar in the first iteration is recognizably Nicholas II, by 1920, he is shown here as a generic figurehead. Likewise, an archetypal bourgeois man (complete with a bag of rubles) stands in for the kulak. Such changes are consistent with a growing trend toward allegory in Soviet posters. Whereas most posters printed in 1920 depicted military efforts, this scene shows a battle between good and evil in broader terms. Here, the idealized bodies of the proletarians offset the abstract, angular bulk of their foes, establishing stylistic tensions which would play out over the next decade of Soviet design.

Virginia McBride is a Peter Krueger curatorial intern in the Department of Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She studies art history at Kenyon College.