Helen Hokinson, or “Hoky” as her friends called her, contributed nearly 1,800 cartoons and vignettes and 68 cover designs to The New Yorker in the first half of the 20th century. Her long-lasting association with the magazine began just a few months after it launched, when a drawing of a round, middle-aged woman standing on the edge of a dock and enthusiastically waving good-bye to a departing ship was published in the July 4, 1925 issue. Hokinson had moved to New York City from Chicago in 1920 to pursue a career as a fashion illustrator and completed work for Lord and Taylor, B. Altman and Company, and John Wanamaker. She had also explored her comedic side in a short-lived comic strip that she created with her friend Alice Harvey titled “Sylvia in the Great City” for the New York Daily Mirror. While studying at the School of Fine and Applied Arts (now Parsons), Hokinson’s instructor Howard Giles was shown her drawing of the waving woman and responded with laughter, encouraging her to try submitting such pictures to magazines that featured cartoons.

Hokinson took an anthropological approach to her assignments for The New Yorker, investigating various locations and events in New York City and recording what she observed. Initially her drawings appeared without captions, but eventually editors started captioning her drawings and making suggestions for situations to draw. In 1931 she met James Reid Parker, a writer for the magazine, and they began a collaboration that lasted for the next eighteen years. Parker convinced Hokinson to focus her efforts on suburban, upper middle class women, and the “Hokinson Woman” was born. This type of woman spent her hours shopping, gardening, and attending club meetings, theatrical performances, flower shows, and pet shows. She was very concerned about club work and civic duties, unafraid of trying new things or being laughed at, and perplexed at times by modern life. “Hokinson Women” could also be recognized by their distinctive plumpness, perky noses, and tiny feet.

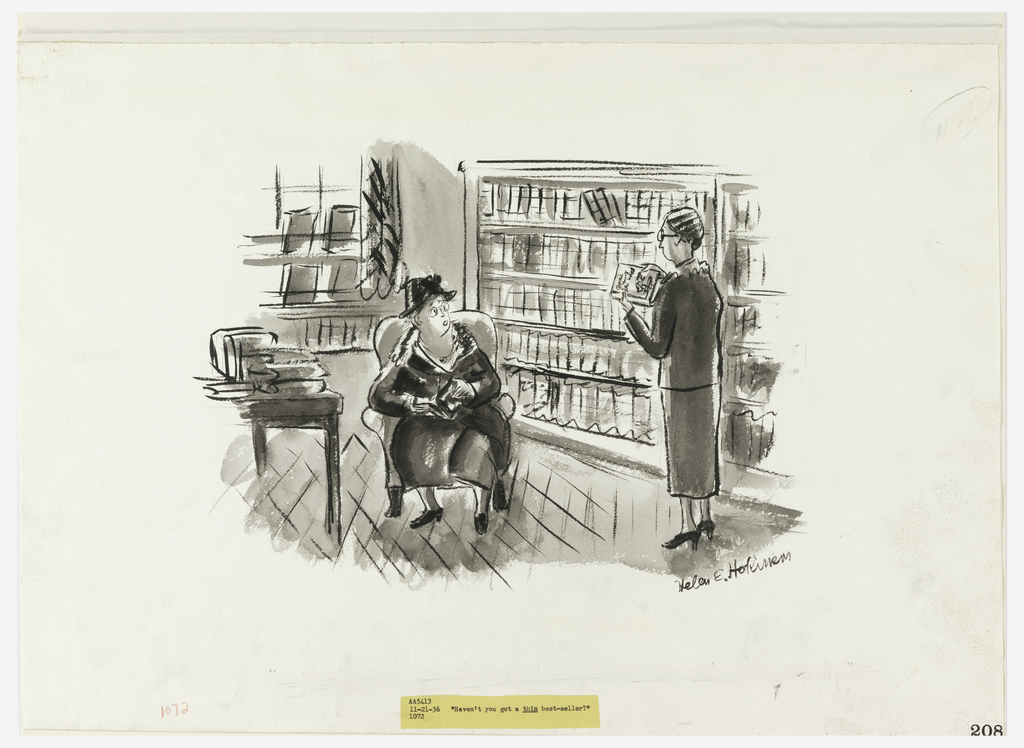

This drawing, published in the November 21, 1936 issue of The New Yorker, features a typical “Hokinson Woman” seated on a large chair in the middle of a bookshop, asking an attendant, “Haven’t you got a thin best-seller?” The attendant is holding a hefty copy of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, published in 1936. Working with gray wash and an energetic, fluid line, Hokinson portrays the seated woman with the earnestness and fearless sincerity that is characteristic of all “Hokinson Women.”

Although Hokinson drew attention to her characters’ imperfections, she always portrayed them with affection and compassion. While attempting to write a play with Nancy Hamilton, an author of Broadway comedy hits, her reluctance to have her characters laughed at prevented the project from coming to fruition. Hamilton wanted to add dramatic conflict to the play by making one or two of the women catty, and Hokinson cried, “But my women are honest, they’re good, they’re well-meaning!”[1] Although Hokinson was self-effacing and shy, she began to feel as though people were laughing at her women rather than with them. She undertook a public appearance crusade to help explain her work and defend the women from being unfairly ridiculed. Tragically, while en route to one appearance at the opening of a Community Chest Drive in DC, she died in a plane crash. This cartoon serves as a reminder of her gentle, affectionate sense of humor and enthusiasm for documenting urban life and interpreting the social scene.

[1] Dale Kramer, “Those Hokinson Women,” The Saturday Evening Post, April 7, 1951, 25.

Carey Gibbons is the Cataloguer in the Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.