Meet the Hewitts: Part Six explored the origins of the Cooper Union Museum, retracing the Sisters' steps in Paris. This “snippet” tells of the wonderful gifts to the fledgling museum by wealthy patrons and admirers of the accomplishment of the Hewitt Sisters.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Godmothers and Miracles: 1897-1920

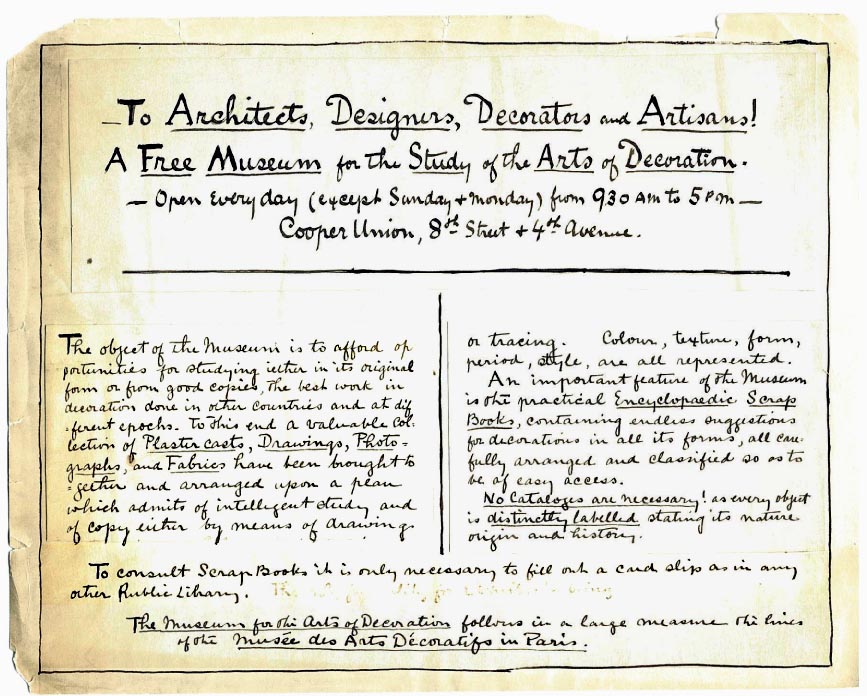

Handwritten announcement of “A Free Museum for the Study of the Arts of Decoration.” Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

Either Sarah or Eleanor proudly penned and posted this 8" x 10” announcement. The Cooper Union Museum, staffed with volunteers from the sisters’ wealthy friends and members of the Cooper Union Art School staff, was free and accessible to all.

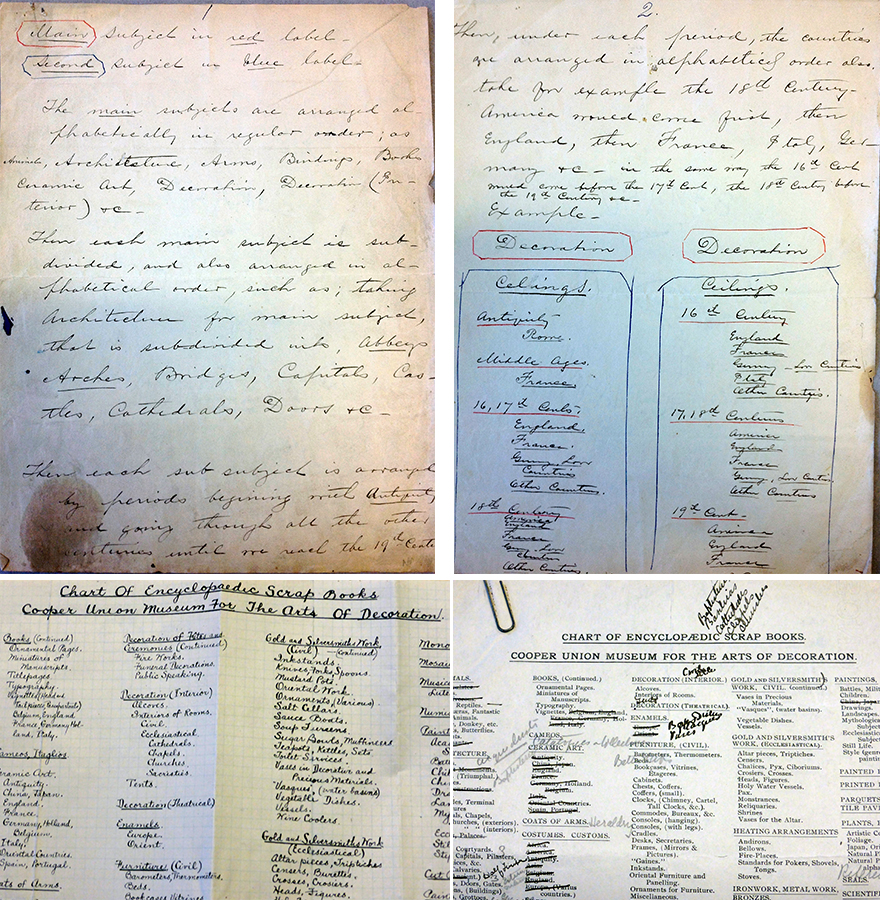

Following the example of the Musée des Arts, Eleanor created encyclopedic reference charts, which classified in great detail architecture and decorative arts into centuries, countries, and periods. She painstakingly fine-tuned her information, as can be seen below in handwritten copies and drafts of a printed version. From these charts, volunteers had compiled 450 encyclopedic scrapbooks with pictures of every aspect of the decorative arts by 1902, a number which grew to 1,000.

Encyclopedic reference charts. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Fabulous gifts came to the Museum in its early days. Eleanor wrote in Making of a Modern Museum:

Then came a wonderful series of happenings. Manufacturers and dealers came

forward with unsolicited help . . . and gave objects suitable to make small exhibits

covering the various branches of the textile and ornamental trades, while the

immediate family was laid under heavy contribution.

Poor Mrs. Hewitt suffered the most, and, as she looked about her devastated

home, would often say, “I wonder where that is?” or, when visiting the museum,

“didn’t I once have something like that?” thinking she recognized some cherished

object.

Porcelain object, ca. 1745. Collection of Mrs. Abram S. Hewitt. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

Friends of the Hewitt family followed suit, making generous contributions of gifts and objects. In 1898, George Campbell Cooper, Peter Cooper’s nephew, gave hundreds of engravings and woodcuts by Durer, Rembrandt, and many others. This gift was the foundation of the museum’s collection of drawings and prints.

Engraving and etching on paper by Andrea Mantegna, ca. 1500. Gift of George Campbell Cooper, 1896. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

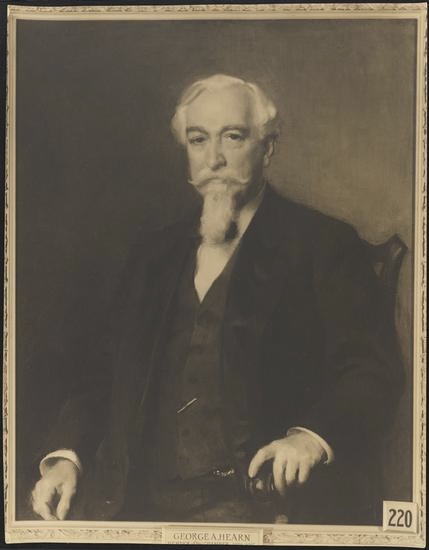

“Gifts of wonderfully suited objects, and generous gifts of money were brought each year by Santa Claus,” Eleanor wrote. His name was George A. Hearn, who in 1907 formed the Council for the Museum for the Arts of Decoration of the Cooper Union, composed of prominent philanthropists, industrialists, and artists whose purpose was to finance and advise on collections for the museum. The Council functioned generously until 1927, and grew to 50 members, at some point including J.P. Morgan, Jacob Schiff, and Louis C. Tiffany.

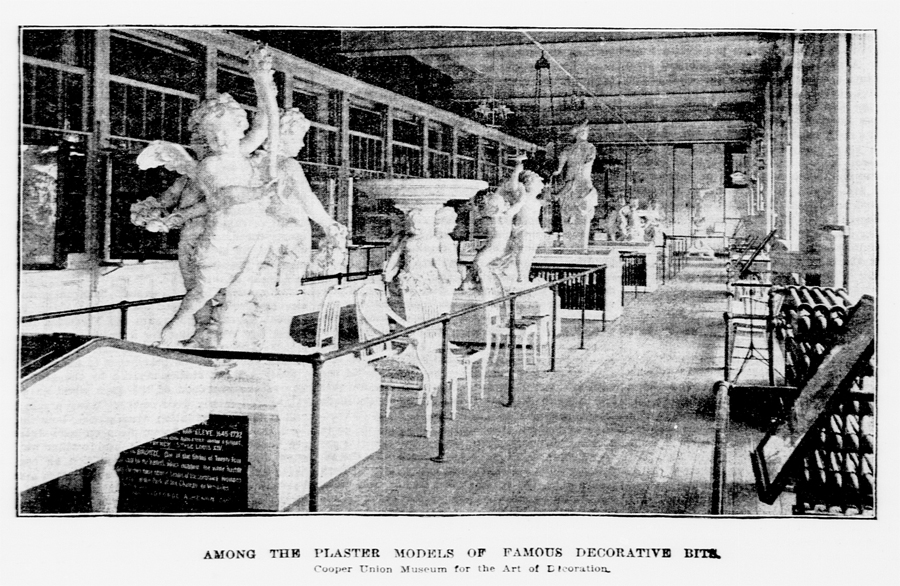

The George A. Hearn gift of sculpture. New York Tribune Illustrated Supplement, June 7, 1903.

Portrait of George A. Hearn. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

“Some Fairy Godmother must have been working overtime waving her wand” as Eleanor and Sarah learned that Signor Piancastelli, Curator of the Borghese Gallery in

Rome, had decided to dispose of his collection of 4,000 drawings of the 17th and 18th centuries, artists’ sketch books, and original designs for ornamental decoration. “The purchase of four thousand dollars was contributed, as if by magic, by friends of the Museum.”

Drawing by Filippo Marchionni, “Window cases with alternate suggestions,” 1750–70. From the Piancastelli collection. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

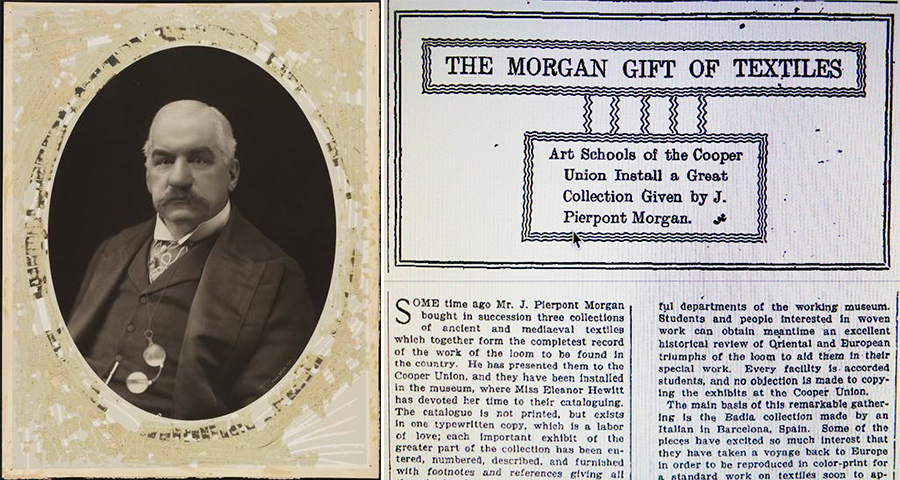

A major gift of one thousand rare textiles was provided in 1902 by J.P.Morgan, who at a dinner with Abram Hewitt, asked “in his usual abrupt, impulsive way, what Mr. Hewitt’s daughters were interested in.” After being told about the sale of the unique Badia Collection of Textiles in Barcelona, J.P. Morgan promptly followed up and cabled: “Have purchased the Badia Collection of Barcelona, also the Vives Collection of Madrid, and the Stanislas Baron Collection of Paris. I do this to give your daughters pleasure.”

J.Pierpont Morgan portrait. Collection of the City of New York; b. New York Times, June 5, 1904.

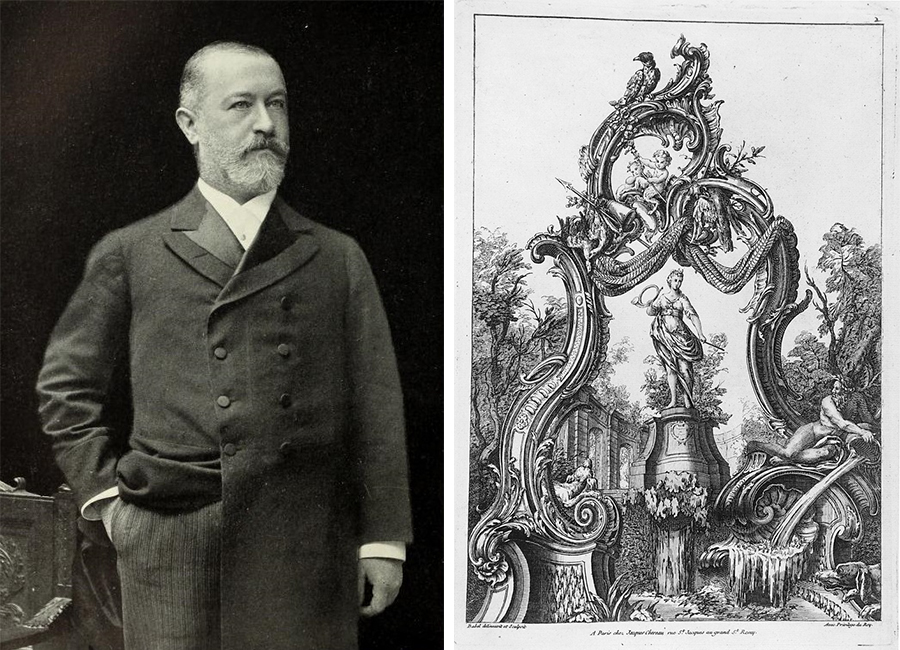

In 1908, Eleanor urged the Council for the museum to arrange the purchase of the important Decloux collection of drawings and furniture mounts. Wealthy philanthropist and art collector Eleanor Blodgett stepped up to the plate and gave $10,000 in honor of her mother. In 1911, a collection of Decloux prints and books was financed by Jacob Schiff, Charles Gould, and Thomas Snell.

Jacob Schiff portrait; b. Engraving from the Decloux collection, “Cartouche and Fountain with Diana,” 1738. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

Although the sisters had a general rule of not exhibiting objects later than the first quarter of the 19th century, this rule did not apply to American artists’ work, especially sketches and drawings, of the last half of the 19th century. In 1912, Mr. Charles Savage Homer, Jr. Winslow Homer’s brother, gave more than 300 drawings and 20 to 30 small paintings to the museum following Homer’s death. In 1917, this gift was followed by more Homer paintings, as well 100 drawings and watercolors by Thomas Moran, a gift of the artist, and 2,000 oil and pencil sketches by Frederic Edwin Church, given by his son Louis P. Church.

Drawing by Frederic Edwin Church, 1887. Gift of Louis P. Church, 1917; Drawing by Thomas Moran, 1871. Gift of the artist, 1917; Drawing by Winslow Homer, 1879. Gift of Charles Savage Homer, Jr., 1912. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

When the Alexander Drake Bird Cage Collection was offered for sale in 1914, the price of $1,300 was met by the sisters. In Eleanor's words:

The objects are there for use, to be worked from, and, if so desired, to be removed

from their position and placed in any light. They can be photographed or

measured . . . . People come to this museum to learn . . . and the arrangement of

the Museum in small sections and with a mass of objects in each . . . does invite

comparison and discussion as to material, workmanship, and design.

Birdcage, mid-19th century. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

Photograph of students in the Decloux room, 1920. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum.

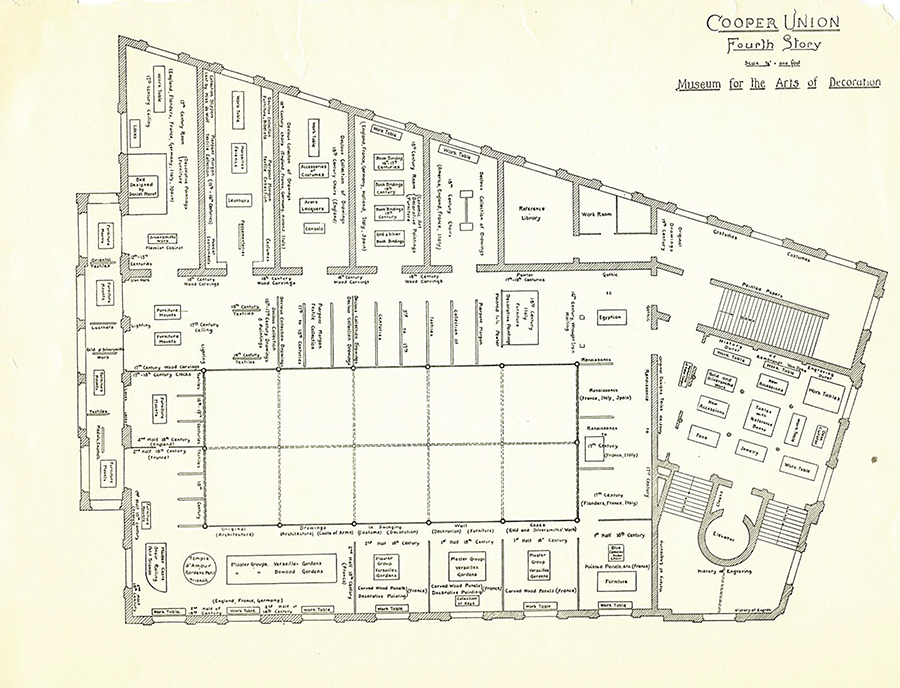

Diagram of Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, 1913. Courtesy of Cooper Union Library Archive.

In 1905, Constance Hare (Mrs. Montgomery) organized with enthusiastic support from Sarah and Eleanor the Au Panier Fleuri workshop and store with the purpose of offering employment to students and graduates of the Cooper Union Woman’s Art School. Merchandise created and sold included painted furniture, screens and murals, jardinieres, and all kinds of custom work inspired by the museum collections. It became a hugely profitable enterprise and attracted prominent interior decorators, such as Elsie de Wolfe. In 1922, Au Panier Fleuri was sold to a Cooper Union Art School graduate and its profits created an invested fund of $20,000 to be used for museum purposes.

Photograph of Elsie de Wolfe. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

An Interactive Timeline of the Cooper Hewitt World

Full timeline is available here.

Sources

The Making of a Modern Museum, by Eleanor G. Hewitt, 1919. Online at http//archive.org/details/makingofmodernmu00hewi.

Archives and Libraries: Cooper Union Library Archives; Smithsonian Institution Archives; Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum and Design Library

Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum collections. Online at collection.cooperhewitt.org

Coming Up

Summertime at Ringwood and Bar Harbor