Written by Marguerite Montecinos-Deppe

The United Nations has designated 2022 the International Year of Glass. Cooper Hewitt is celebrating the occasion with a yearlong series of posts focused on the medium of glass and museum conservation.

The functional role of glass today has expanded far beyond what ancient artisans could have imagined. Due to continual advancements in digital technology and the mechanisms through which information is conveyed, glass is one of the main material components in visual communication devices. Google released its first smart glasses known as the Google Glass Explorer Edition in 2013. Smart glasses are a wearable technology that superimposes information on the wearer’s field of view via a display housed in a headset. The example in Cooper Hewitt’s collection is a beta (test) version of Google Glass that was available to the public only from 2013 to 2015. After mixed reviews, negative press, and public outcry over privacy concerns, Google Glass lives on today as an enterprise-only product, used mainly by manufacturing businesses but no longer available to the average consumer.

Google Glass Explorer Edition XE-C 2.0 Optical Display Device, 2013; Design Director: Isabelle Olsson (Swedish, born 1983); Manufactured by Google X (Mountain View, California, USA); Titanium, plastic, steel, electronic components, LED, silicon, liquid crystal, carbon, glass, copper; H × W × D: 2.5 × 13.5 × 21 cm (1 × 5 5/16 × 8 1/4 in.); Gift of Robert M. Greenberg, 2017-51-13-a/e

The beta version in Cooper Hewitt’s collection marks a significant development in minimalist wearable design. This version, named Google Glass Explorer Edition XE-C 2.0, was designed by a team led by industrial designer Isabelle Olsson. Google Glass could communicate pop-up news alerts, text, and navigation directions. A track pad on the side of the lens-less glasses was controlled by swiping it with backward, forward, and tapping motions. A camera was operated by voice command or by holding down a button on the arm structure. Phone calls and text messages were also made via voice command; however, they were dependent on a Wi-Fi connection or mobile tethering since this iteration of Google Glass was not connected to a cellular data network.[i]

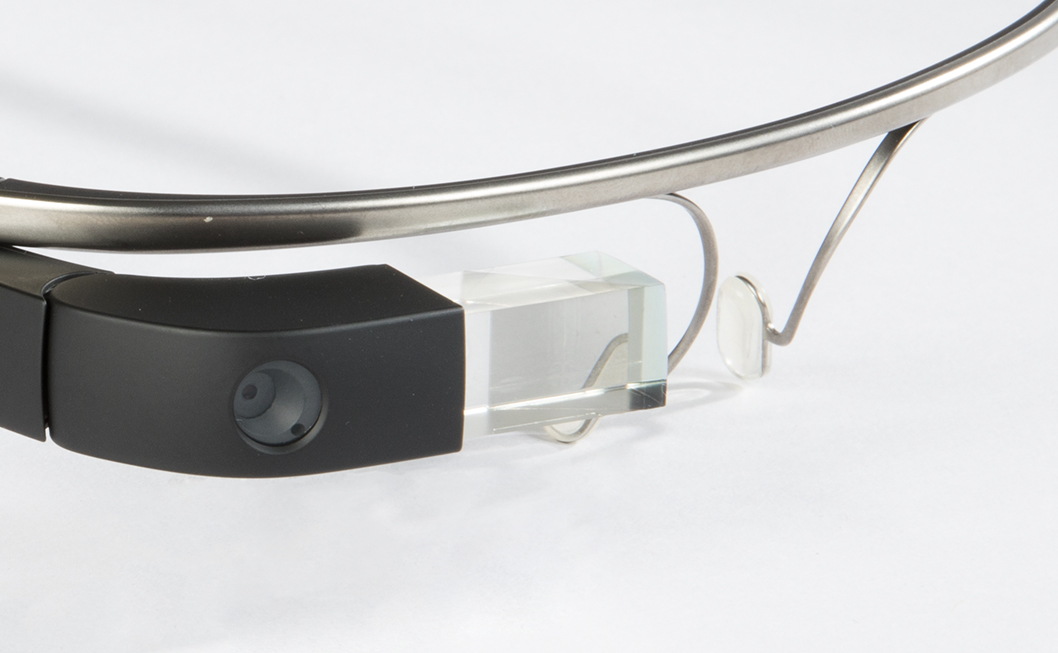

The most exciting feature of smart glasses like Google Glass is the use of augmented reality: a layering of digitally generated information, such as a map, superimposed over the wearer’s view of the real world. To achieve this, a tiny square glass prism, fixed to the upper right temple arm, hovers as a display just above the wearer’s vision line. The frame also contains a mini projector that transmits digital information through the semi-transparent prism onto the user’s retina. Prisms have been critical in the history of glass and the history of science as far back as the work of Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727) who used a dispersive triangular prism to break white light into a spectrum of colors. With Google Glass, the prism allows for the controlled direction of the digital image. An optical prism made of glass is designed to refract light from one surface to another without using a mirror for reflection and instead bending the light as it enters and exits non-parallel sides. Google Glass Explorer’s combined use of the prism and micro-projector solves the challenge of keeping the projected layer of information sharp and in focus via a polarized beam splitter.

Detail of the camera and prism on the Google Glass Explorer Edition.

The design intent behind Google Glass was to reduce the device down to its minimal features. According to Olsson, with the beta version, as compared with an earlier, bulkier prototype, the design goals of “lightness, simplicity, and scalability” were combined with “functionality, beauty, and weightlessness.”[ii] This minimalism enhances Google Glass’s functionality in providing information while leaving the user’s hands free for other activities or tasks, making direct communication more immediate and transparent.

As the technology, miniaturization, and materials behind smart glasses advance and the use of these devices expands (for example with Meta and Rayban’s recent release of their Stories smart glasses), there are greater personal and collective concerns to ponder. Such devices raise ethical questions about acceptable personal and societal standards of transparency, privacy, and the potential for surveillance.[iii]

Marguerite Montecinos-Deppe was Cooper Hewitt’s CUNY Cultural Corps intern (2021–22).

Notes

[i] Brian Fung, “We’re using a ton of mobile data. With Google Glass, we’re about to add a whole lot more,” Washington Post, July 30, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2013/07/30/were-using-a-ton-of-mobile-data-with-google-glass-were-about-to-use-a-whole-lot-more.

[ii] Isabelle Olsson, “Make it Simple GRID14,” Bonnier, September 8, 2014, https://vimeo.com/105589857.

[iii] Mat Honan, “I, Glasshole: My year with Google Glass,” Wired, December 30, 2013, https://www.wired.com/2013/12/glasshole/.