When we first began to build out our plans for the Interaction Lab, we were already certain public programs would play a big role in our work. We conceived of our public programs to convene a variety of audiences for shared learning, exploration, and discussion on topics related to our work reimagining the visitor experience at Cooper Hewitt. Reflecting the Lab’s values in the structure of our events was critical to their success, so, we designed the programs around these priorities:

- Share provocations, ideas, frameworks and approaches that inspire us in our work

- Create opportunities for people to meet and genuinely engage over thoughtful conversation

- Begin to build a community of practice around new approaches to visitor experience design

Over the first four programs we’ve run to date, we’ve experimented quite a lot with format. Each has been organized around a central theme, introduced in detail, with one or more talks up front. Those talks are then followed by a participatory portion, where participants are invited to put their minds to work on the topics they’d just been presented. To close every event we hold a group discussion to share thoughts and synthesize learnings as a community.

We’re looking forward to expanding our event series by introducing other kinds of programming— professional workshops and collaborative design sessions—that invite participants into our design process to learn and explore alongside us. We had a plan that we were excited to execute. But all of a sudden, we find ourselves in a completely altered world.

In the past weeks we’ve seen a mad dash by every kind of organization to “go online.” Surprising no one, video conferencing-style interactions are proliferating by orders of magnitude. It’s one of the most obvious and valuable tools we have to rapidly transition to this new world of physical distancing. Concurrently, enforced physical distance has handed us a firm mandate to experiment with all available communication platforms and quickly devise new systems of working that don’t depend on co-location to do so much of the work that we do. I believe this time apart will reveal large flaws in our previous assumptions. I believe it will begin to demonstrate what’s really possible in a remote setting–what many disability activists have been telling us for years. I expect what we discover will surprise us.

In a few short weeks, I’ve already observed a level of connectedness that I hadn’t experienced before in my life, except maybe while living in college dorms, constantly physically surrounded by peers. This global crisis has awakened us suddenly and simultaneously to the true connective potential of the interactive technologies that now sit in our pockets. That’s why the Lab has chosen to see this situation as an opportunity (!) to propose better alternatives to deeply flawed legacy systems that we’re being forced to abandon for other reasons.

Rather than trying to predict or plan, we’d like to propose a different approach. Let’s explore. Planning is an activity that presumes we understand what the After looks like. (After being the magical and unspecified time that follows Now.) The truth is, it’s still too early to tell what’s going to happen. Though we’re certainly capable of charting the path of a curve, there are still too many variables, and too many new circumstances emerging too quickly. In the meantime, there’s lots we can do. We can observe, experiment, and learn, together. We can track what’s emerging as it emerges, assess what we like about it and what we don’t. We can refine our approach until we’re satisfied, and document our findings as we go. When the time comes to open our doors once more, we can leave what wasn’t working in the past, and integrate successful practices we’ve uncovered into whatever After we will build together.

Angela Perrone (Cooper Hewitt Gallery Technology Assistant) and her poodle, Francis at their home campsite.

Expanding our understanding of the possible.

Social distancing and self isolation are difficult and unfamiliar, but for those of us thinking about how to engage with remote audiences (read: all of us), we can and should consider it an exercise in experience design. As we explore how to bring our own programs forward, we wanted to share our thinking about the process, starting with thorough examination of constraints and affordances to establish what’s possible and desirable. Because we find ourselves so constrained in this moment, let’s start there.

As of the time of this writing, more than 2 billion people across the world are obligated to stay home, while others live with varying degrees of restricted movement. Many of us have friends, colleagues, and loved ones who are sick and/or have lost work. Those of us who can work from home are doing so under less than ideal physical circumstances and ultra-challenging emotional circumstances, and those who cannot are braving risks to ensure the rest of us are taken care of. Those without the privilege of safety, or in otherwise vulnerable positions, just saw our lives become even more precarious. Processing the news requires a lot of mental energy, further augmented by the recent dramatic increase in verbal communication, stress, and uncertainty about the “After” are never far away.

I bring these things up not for the sake of creating an emotional pile-on but to acknowledge the seriousness of the situation. People are struggling, stressed, and scared. It’s critical that we engage with this truth, so we can integrate an understanding of it into our approach. Let’s not sugar coat it. The constraints are intense, very new, and difficult, without a doubt. However, there are real opportunities to design our way through this, if we identify what affordances we do have available, and build on them to the greatest extent possible.

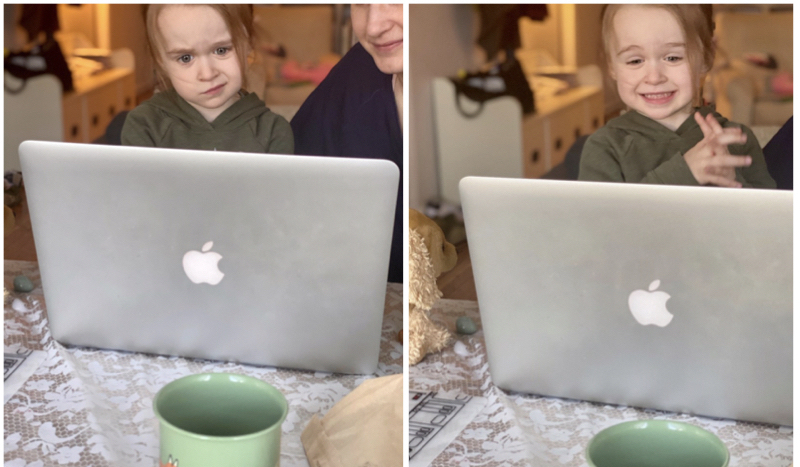

Ella Tickle-Matei (daughter of Ashley Tickle, CH Marketing Director) attending her first online preschool class

Most of our audience is at home.

“Home” is one of the most intentionally designed spaces on earth. Whether we rent or own, and have designed the edifice to meet our needs or have chosen the things inside it, “home” is most often full of the people, animals, and things we choose to invite in. At home, we’re surrounded by the familiarity that we’ve designed for ourselves and other members of our households, furnishings and possessions arranged to facilitate our individual ability to comfortably move through our days, whatever they may look like. Home is intimate space; it’s where we live our most personal experiences, surrounded by the people, animals and things that mean the most to us.

For designers, this means…

You have access to everything your participants have access to. That your audience is joining you from their home turf means they’re surrounded by resources for you to design with. Think about how you’d like them to experience your time together. Think about the kinds of feelings you’d like to create for them. Do they need to be alert, or better in repose? Should they get a drink or a snack and settle in for a long program, or will there be a break? How might we collaborate with our audiences to design how they experience the time we spend together? Thinking this kind of thing through in advance will show your audience that you’ve considered them in your planning, and will help them help you.

Considering the emotional dynamics of entering people’s homes. If you gain your audience’s trust, you may even gain the opportunity to collaborate in augmenting that intimacy. Imagine how you might connect to a young child by injecting a sense of wonder into their bedroom, or bring new liveliness to the dining table by turning it into a puppet stage at lunchtime. Because once that table becomes a puppet stage, even if it doesn’t remain one for long, everyone who saw it will always remember it. A well run program under these circumstances has the potential to bring new energy into the homes of your audiences, enriching the way people experience their space. That kind of impact is lasting, and will not be soon forgotten.

One last note on home – one of the largest social inequities being highlighted by this crisis is for those people who are experiencing homelessness, housing or food insecurity, or for whom home is an unsafe space. Important to remember that safety is a privilege at all times, in crisis and otherwise. Designing with this in mind means using language and approaches that consider different kinds of experience, such that we don’t leave anyone out for lack of resources.

Screenshot from Monthly Weekly Meetup, organized by Adam Quinn, Digital Product Mgr.

Plenty of platforms to choose from.

As of now the vast majority of remote programming takes place via some kind of video conferencing platform, of which there are very many to choose from. In terms of features, they offer all kinds of ways to connect with each other in pairs, small groups, and large, for broadcasting in real time, for small group discussion, and for recording and posting later. Each of those platforms does more or less the same thing, but has slightly different features that can be used as they’re designed to be, or hacked for an entirely different effect.

For designers this means…

Selecting a platform based on the needs of your audience. Start with a real and meaningful assessment of what it is you want audiences to receive from the program you’re designing. This could be something formal like a learning objective, or could be more practical and qualitative, like “creating a meaningful connection with a new person.” Next, work backwards from your objectives to assess what kind of interaction with your audience would be best suited to the task, and select your platform accordingly. Some things to consider:

Is your program designed for one or more people to broadcast, or to be more interactive? Are you designing your format to be one-to-many (like a lecture), few-to-few (like small group work), or many-to-many (like large scale interactive events)? Either way, there’s a platform for that! (Think: social media “live” vs. video-conferencing). When assessing which platform to use, make sure to remember your audience and consider their needs and level of attention as you refine your approach accordingly.

Create value for audiences participating live, as opposed to accessing a recording on their own time. In the process of deciding where and how to execute your program, consider when, why and how your audience might decide to attend, design accordingly, and share your thinking! This will help audiences make an informed decision about how to engage in the way that’s most convenient for them (which they’ll do anyway, with or without your guidance).

Giving clear instructions on how to use the platform you’ve selected. Because remote audiences are co-creating your event with you by designing their own experience while attending, it’s critical to help them help you deliver a fantastic program. Identify the specific features that you’ll be using to deliver your program and build in time to on-board your audience. Things like indicating what kind of view (speaker or gallery), providing guidelines for how and when to ask questions, use the chat feature, or move into breakout rooms will manage audience expectations and help your audience feel comfortable and considered.

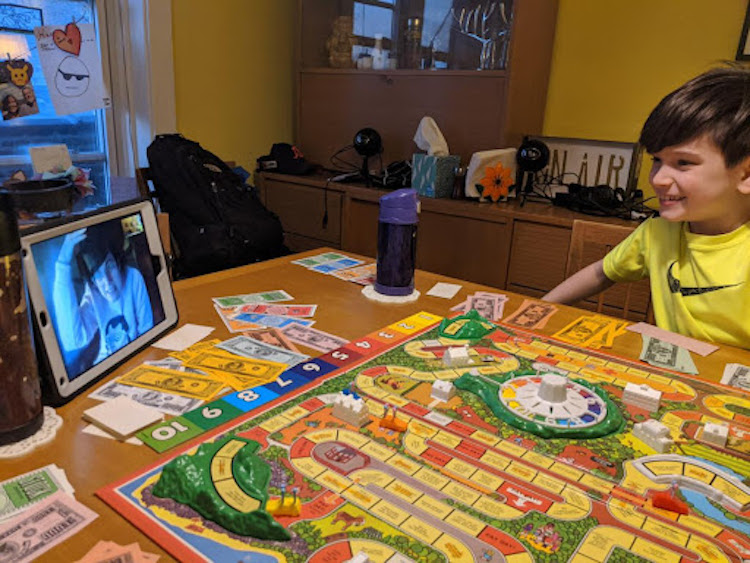

Kim Alpert (Rachel’s longtime friend and collaborator) and her nephew playing a board game remotely

Now is the time to design with compassion.

Designing for this moment requires more than thinking about the logistics of remote interaction. It’s critical to give honest consideration to what our audiences might be experiencing right now. In these challenging and uncertain times, we can offer engaging, surprising, joyful experiences that stimulate thinking and learning.

For designers this means…

Thinking about timing. Now that we’re not necessarily bound by the same constraints, what might be a good time of day to offer the kind of engagement you’re planning? Who do we want to be there? What else might be happening during the day that would be helped/hindered by this?

Offering formats that are friendly for the whole family. With kids at home for the foreseeable future, creating opportunities to engage children will be a gift for parents struggling to balance work and family at the same time (read: all of them). What might we adjust in our approach that would make our programs suitable for kids, especially older ones? What might this teach us about how to make our programs more accessible in general to a wider range of audiences?)

Engaging through many different modes. There’s so much watching and listening going on while everyone is at home. How might we minimize those kinds of passive activities in favor of more making and doing? Being in our homes, we’re already limited in our physical activity. How might we create opportunities to engage differently?

Leaving our old biases behind us. Now is an excellent time to take a good, long look at how we’ve been designing events and for whom. In the process of rethinking approaches, centering accessibility in your process is key. How might we design online programming to include participants with disabilities? This means considering a range of abilities in decision making around program format, the language you use to describe what it is that you’re doing, and selecting platforms with robust accessibility features.

What’s next for the Interaction Lab?

As we look to the coming weeks and months we’ll be experimenting with how to deliver our public programs in a remote format. For us, this is really three challenges rolled into one.

Reimagining a participatory format to be facilitated remotely. This is a challenge that almost all people and organizations are facing right now, and we are no exception. We have lots of ideas about how to do this, and have been lucky to experience some really innovative examples thus far.

Thinking about the physical space of the museum without being able to access it. One of the core purposes of our programming is to create space to collaboratively reimagine the museum experience. Without the physical space of the museum to reference, this becomes much more difficult.

Integrating collaborative, practice-based research into online programs. The Interaction Lab’s events double as collaborative design sessions that contribute to our reimagining of Cooper Hewitt’s visitor experience. As such, these public programs are an integral piece of our work. Without them we would lose opportunities to engage our audiences in collaborating on the work itself, which is vital to our approach.

As we design programs to roll out in the coming weeks, we’re going to think carefully about what we ask of our audiences, while offering joyful and stimulating interactions that will hopefully enrich our audiences’ time away from their normal routines. It’s important to us to keep creating space to interact with the dynamic, generous community we’ve built in these past months, but we also understand that in uncertain times cognitive bandwidth is precious. Though the circumstances are difficult, we are genuinely excited to develop programs that continue to advance our work, and bring us together to learn and explore, even while we’re apart.

We’ll continue our public program series in April with a series of three interactive workshops that explore information design for museums through creative exercises. We’ll be communicating details about the event, and how you can participate very soon.al

Rachel Ginsberg is the Director of the Interaction Lab, Cooper Hewitt’s newly launched visitor experience design lab. The Interaction Lab is bringing interactive design methodology to the very heart of Cooper Hewitt’s visitor experience—across digital, physical, and human interactions. To keep track of Lab activities, sign up for our mailing list.

One thought on “Designing for Now: The Implications of “Going Online””

Olivia on December 5, 2020 at 6:16 pm

nice!