A pork shank flies through the air, flanked by nine Allied bombers. Perspective lines shoot out from a distant point of origin, emphasizing the speed, impact, and patriotic urgency of the heroic ham and her military escort. But why?

Signed “herbert bayer” in the upper left corner, this mysterious black-and-white printed photomontage is part of Cooper Hewitt’s remarkable collection of Bayer’s work, acquired in 2015. The piece arrived at the museum trimmed and pasted to a sheet of heavy black paper—whatever promotional context had once surrounded the photomontage is gone. Perhaps the image had been prepared for the designer’s portfolio or an exhibition.

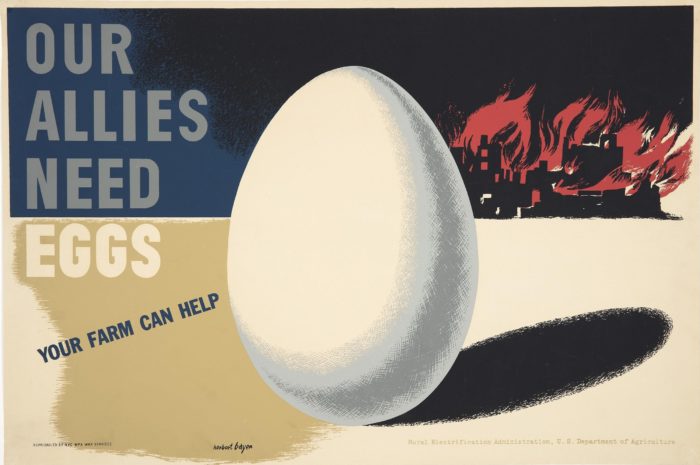

While researching the exhibition Herbert Bayer: Modern Master (November 16, 2019–April 5, 2020), we found a tiny reproduction of the complete advertisement in the Denver Art Museum’s 1988 guide to their own extensive Bayer collection.[1] The headline reads, “A Victory Recipe: Pork and Planes Cooked by Gas!” The ad was published in 1942, a time when many government propaganda campaigns sought to encourage thrift or boost production in order to support the war effort. Bayer’s 1942 poster “Our Allies Need Eggs” juxtaposes a giant egg with a burning city; published by the WPA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, this poster pushed farmers to produce more eggs.

Poster, Our Allies Need Eggs; Your Farm Can Help, ca. 1942; Designed by Herbert Bayer; Lithograph; 51.1 × 76.4 cm (20 1/8 × 30 1/16 in.); Collection of Merrill C. Berman

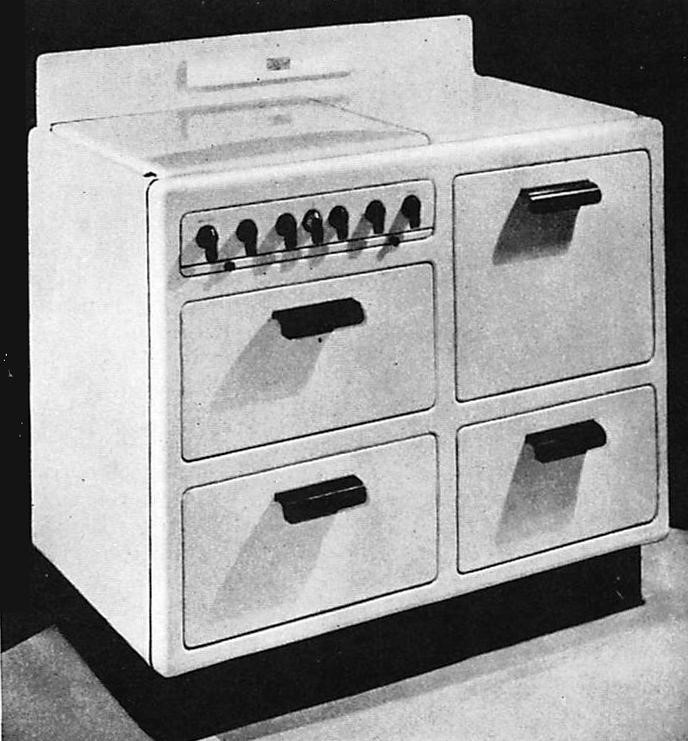

It turns out, however, that Bayer’s Victory Recipe ad has only a symbolic link to the war effort. Published to promote the gas industry, this campaign tapped patriotic zeal to encourage homeowners to use gas stoves rather than electric ones in their kitchens. In the 1930s and 40s, electric stoves and ovens were marketed as being cleaner, safer, and more modern than gas—and they replaced older gas units in many homes. To make gas stoves more functional and appealing, Industrial designers, including Norman Bel Geddes, designed boxy, modular gas units that matched the height of the continuous countertops of the streamlined kitchens of the 1930s. (A similar stove appears in Bayer’s Victory Recipe ad.)

Norman Bel Geddes, modular stove designed for the Standard Gas Equipment Company, 1933

Why did Bayer cut away the context from his flying ham ad? For one thing, he probably didn’t design the whole advertisement, whose layout is highly conventional apart from the striking image. The flying ham is much more thrilling on its own, and the backstory is…a bit of a letdown.

Ellen Lupton is Senior Curator of Contemporary Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

[1] Gwen Chanzit, Herbert Bayer Collection and Archive at the Denver Art Museum (Denver: Denver Art Museum, 1988), p120.

One thought on “Recipe for Victory”

Sara TOROSSIAN on February 8, 2020 at 2:37 pm

I love Herbert Bayer ,. For me was one of the bigger designer .

Y live in Argentina, is a long way to New York, and in this moment is very difficult for us go .

If I can l do all, to go to see this Expo.

I am Sara Torossian , graphic designer .