What does “typography” mean to you? Does the word stir up contempt for Comic Sans and Papyrus, or does it conjure a death match between Times New Roman and Helvetica? For many of us, the word “typography” means “fonts.” Yet the art of typography encompasses much more than choosing typefaces. Designers use scale, spacing, layout, contrast, grids, hierarchy, and more to arrange content in meaningful and expressive ways. A typographic message can stand up and stand out—or gracefully recede to the background.

Jennifer Morla has experimented with typography since 1978, when she began designing motion graphics for a PBS television station in San Francisco. After founding Morla Design in 1984, she became a leader within the Bay Area’s dynamic design scene. Morla has used color, pattern, photography, and editorial wit to bring grit and sparkle to visual communications for consumer brands and cultural institutions. Morla has a special gift for typography. She mixes, matches, splices, and overlaps lines of text to generate provocative interpretations of art and ideas.

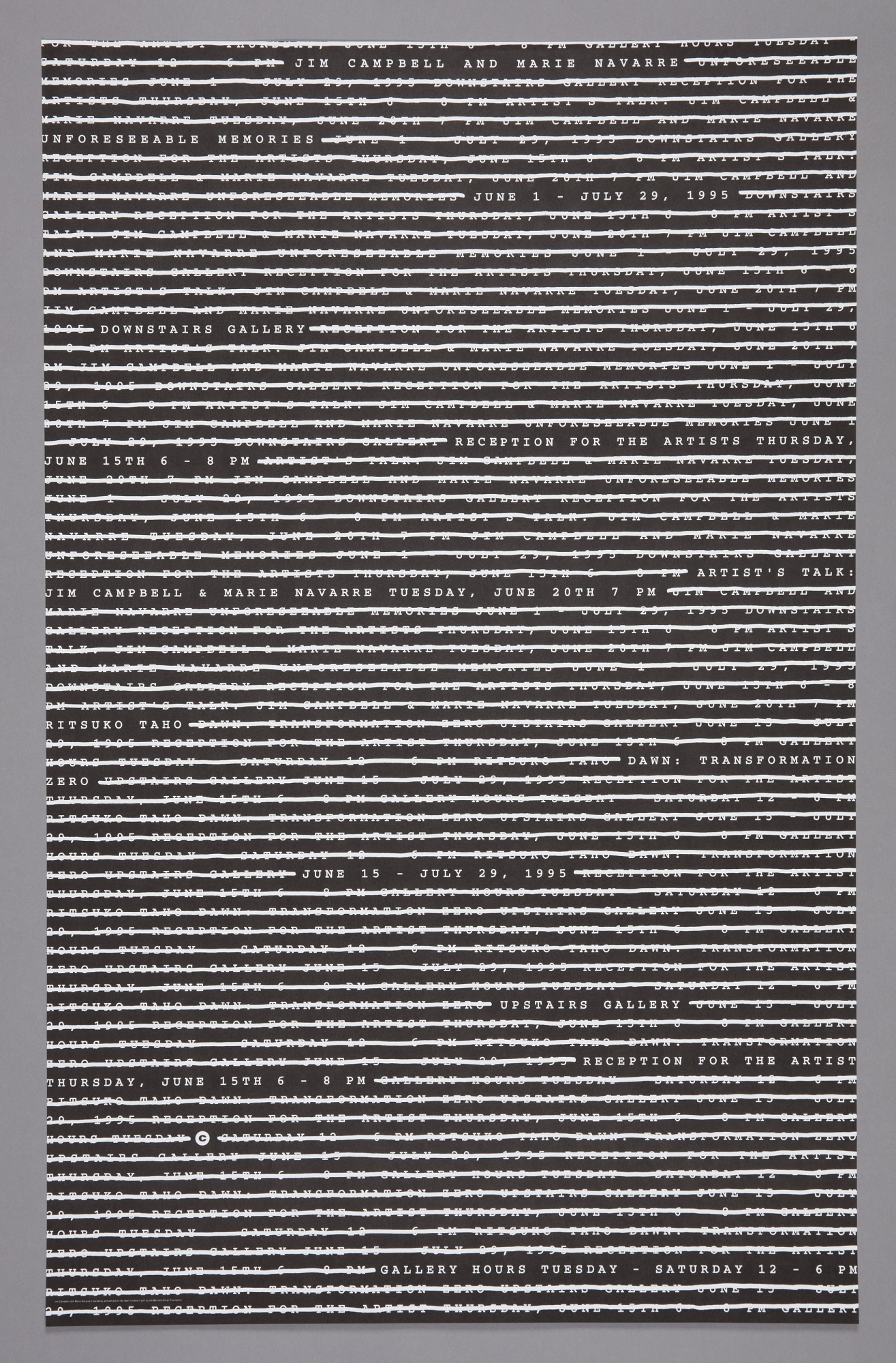

Cooper Hewitt recently acquired nearly two dozen posters and other works by Morla, who received the National Design Award for Communication Design in 2017. A group of black-and-white posters from the 1990s demonstrates her mastery of typography as an expressive medium. San Francisco’s Capp Street Project (now part of the Wattis Institute) offers residencies and exhibition opportunities to local artists. While traditional museum or gallery posters feature reproductions of artists’ work, Morla uses type to embody themes and concepts. For the exhibition “Unforseeable Memories” (1995), she covered the poster with a field of small type, printed in all caps in a simple, monospaced typewriter font—and then she crossed out most of the text. All that remains visible are the particulars concerning the event. Paradoxically, the obliterated lines serve to highlight the remaining text, functioning like underscores. In another poster created the same year, overlapping words convey collaborations among a group of artists. Individual names emerge from the crowd.

For a campus gallery at the California College of Arts and Crafts, Morla assembled fragments and shadows of letterforms into vibrant bursts and clusters. Crisp horizontal bands of text stand out against these gestural masses to announce the title and dates for each exhibition. As a series, these black-and-white posters gave the gallery a recognizable voice while singing different melodies.

Morla’s posters contributed to the flourishing of typographic experiment during the dawn of digital typography. The new design tools that came of age in 1990s freed designers to manipulate type in direct and immediate ways. In place of manual cut-and-paste and costly galleys of typesetting, designers could manipulate the scale, orientation, and sharpness of text and image. Philosophically, designers were questioning modernism’s emphasis on simple, direct messaging in favor of layered complexity. Typography could challenge readers to look closer. In this influential body of work, content becomes visible against a turbulent sea of form and counterform, assertion and deletion.

Ellen Lupton is Senior Curator of Contemporary Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.