Author: Leigh Wishner

In celebration of the third annual New York Textile Month, members of the Textile Society of America will author Object of the Day for the month of September. A non-profit professional organization of scholars, educators, and artists in the field of textiles, TSA provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of information about textiles worldwide.

Taking a snapshot or picking up a photo-postcard of a famous destination is an impulse every modern tourist has experienced; the acquisition of site-specific souvenirs serves a similarly appealing purpose, commemorating vacations to distant locales and encouraging memories to linger. Combining the photograph and the souvenir, fabrics printed with actual pictures—not a designer’s artistic interpretation of geographical place—allowed mid-century sightseers to “wear their postcards” long after arriving back home.

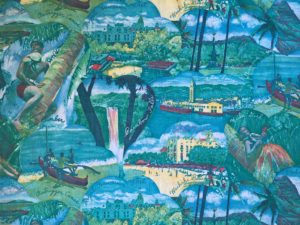

Tourism boomed in the post-war period. Increasing disposable income and leisure time coupled with more affordable modes of transportation (whether personal vehicles, jet aircraft, or cruise ships) made travel more practicable, opening the doors to cosmopolitanism for the average American. A noteworthy byproduct of this tourism surge was a fad for photographic novelty printed textiles characterized by collaged cloud-bubbles containing “documentary” images of natural and man-made landmarks. Known designs include several photo collages of Hawaiian scenes and pastimes, such as this example in the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising Museum collection, and an “around the globe” version with a multitude of far-flung panoramas.

Hawaiian Scenes printed cotton (detail), mid-1950s, the FIDM Museum, 2018.1164.2

A virtual tour of New York City, this printed cotton in Cooper Hewitt’s collection distills the hustle and bustle of the “Big Apple” into overlapping, cloud-like vignettes rendered in a monochromatic palette. Though the repeat is short, the fabric’s width packs in vistas of Times Square, Coney Island, Central Park, and Lower Manhattan as seen from Brooklyn (and over its historic bridge). Other architectural highlights include Grant’s Tomb, City Hall, the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center, Grand Central Terminal, and the George Washington Bridge. Each photo has deliberately scalloped edges and is notated in cursive script for identification. Even the Statue of Liberty—synonymous with New York, and hardly in need of explanation—is labeled. A photograph of the United Nations Secretariat building, a modernist bastion of international diplomacy, helps date this design. Completed in 1952, it is the “youngest” of the monuments featured—meaning it couldn’t have been produced before that year.

Advances in textile printing technology also fueled the trend for photo-printed textiles. Though photographic printing on fabric was not entirely a new process, two methods were introduced by rival New York firms in 1947: Foto-Fab by Lieze, Inc., and Photone by the Ross-Smith Corp. Both employed proprietary chemical blends, impregnating the textiles and transforming them into light-sensitive material which was exposed and developed much in the same way photographic contact paper is treated. The Foto-Fab process, invented by artist/photographer Lieze Rose Stewart and filed for patent in January 1947, used a light source to penetrate a negative film, leaving an indelible positive print on the cloth’s surface.(1) Photone, in contrast, relied on a positive film. A brief piece in TIME magazine—replete with a series of amusing images of photo-printed garments, pillows, upholstery, and wall hangings—noted that “photographic fabrics are the big news of the year” and that though currently limited to “restrained monotones, both pioneering companies are working to develop techniques that will give them full-color photographs on fabric….”(2)

A dynamic jumble of thriving urban locations, this New York “sightseeing” textile may have been printed via one of these methods. It would have been perfect for making into sport shirts, casual skirts, and scarves—items that were easy for tourists to pack in suitcases for the return journey, and served as tangible, nostalgic reminders of time spent in “the city that never sleeps.”

(1) Stewart, L.R. Photographically Printing on Materials. US Patent 2,531,086, filed January 17, 1947 and issued November 21, 1950.

(2) “Photographic Fabrics.” TIME, December 8, 1947: pp. 107-108, 110.

Leigh Wishner is Museum Coordinator at the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising (FIDM) Museum and Galleries, Los Angeles.

One thought on “A Big Apple Souvenir”

claudia phelps on October 20, 2018 at 7:17 pm

Interesting item.