In last month’s Short Story, we attended the weddings of Hewitt sister Amy Hewitt Green and that of her daughter Eleanor Margaret Green, who became Princess Viggo of Denmark. This month, researcher Josephine Rodgers discusses the introduction of American drawing into Cooper Hewitt’s collection through the work of Robert Frederick Blum.

Margery Masinter, Trustee, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sue Shutte, Historian at Ringwood Manor

Matthew Kennedy, Publishing Associate, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Promoting American Art

In 1903, Robert Swain Gifford, head of Cooper Union’s Womans Art School, declared that drawing was essential to the design process. In the Annual Report to the school’s administration, he presented the need for a permanent collection of American figure drawings to serve as models for students to develop their skills. Just a few months after Gifford wrote his plea, the Hewitt sisters helped to secure a major gift of American drawings by Robert Frederick Blum (1857–1903) to the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration. After the artist’s tragic death at 46 of pneumonia, his sister Henrietta Haller took up the mission of securing a home for Blum’s work and promoting his legacy. In 1904, Haller donated 19 sketchbooks (with over 450 individual folios) and over 65 preparatory studies for the artist’s most esteemed Mendelssohn Glee Club mural Vintage Festival, to the Cooper Union Museum. At the time Blum was among the foremost American decorators. With this single gift, the Cooper Union Museum established itself as a repository for American art and by 1920 held major collections of drawings by Kenyon Cox, Thomas Moran, Winslow Homer, and Frederic Edwin Church.

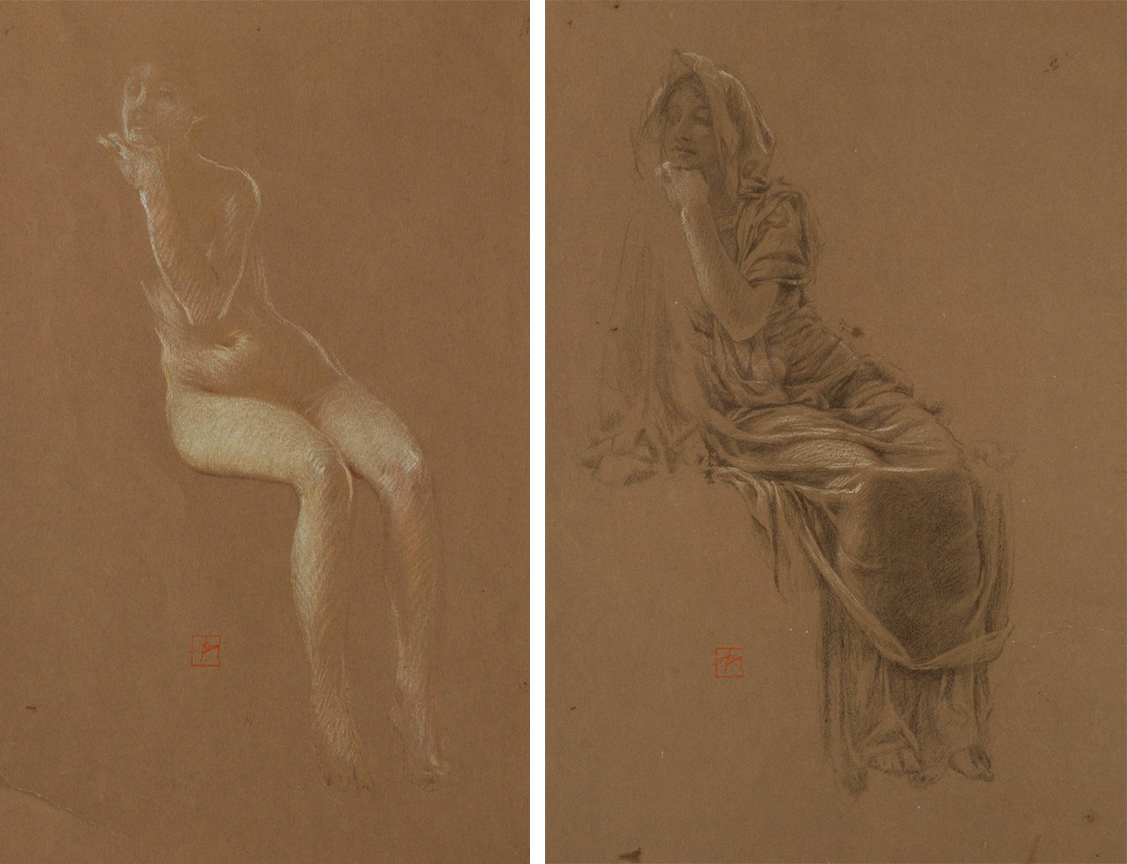

As previous posts have discussed, Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt resolutely gathered European decorative art objects, photographs, and prints during their annual trips abroad to be studied and copied by students at Cooper Union. How did the Hewitt sisters solicit such large gifts of American art? What was their response to European modernism or the progressive American art movements in New York after 1913? Two pastel drawings, both titled Study for a seated woman, “Vintage Festival,” Mendelssohn Glee Club, New York, NY within the Cooper Hewitt collection, can help add a piece to this puzzle.

Fig 1. (left) Drawing, Study for a seated woman, “Vintage Festival,” Mendelssohn Glee Club, New York, NY, 1895–1898; Robert Frederick Blum (American, 1857–1903); Pastel crayon on wove paper; 17 3/16 × 12 1/8 in. (437 × 308 mm.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of Henrietta Haller, 1904-16-17-b; Fig 2. (right) Drawing, Study for a seated woman, “Vintage Festival,” Mendelssohn Glee Club, New York, NY, 1895–1898; Robert Frederick Blum (American, 1857–1903); Pastel crayon on wove paper; 16 7/8 × 12 5/8 in. (429 × 320 mm.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of Henrietta Haller, 1904-16-17-c

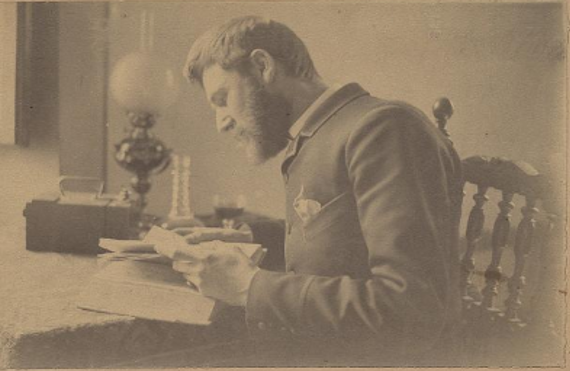

Fig 3. Robert F. Blum, ca. 1875, unidentified photographer, Charles Scribner’s Sons Art Reference Department records, 1839–1962, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

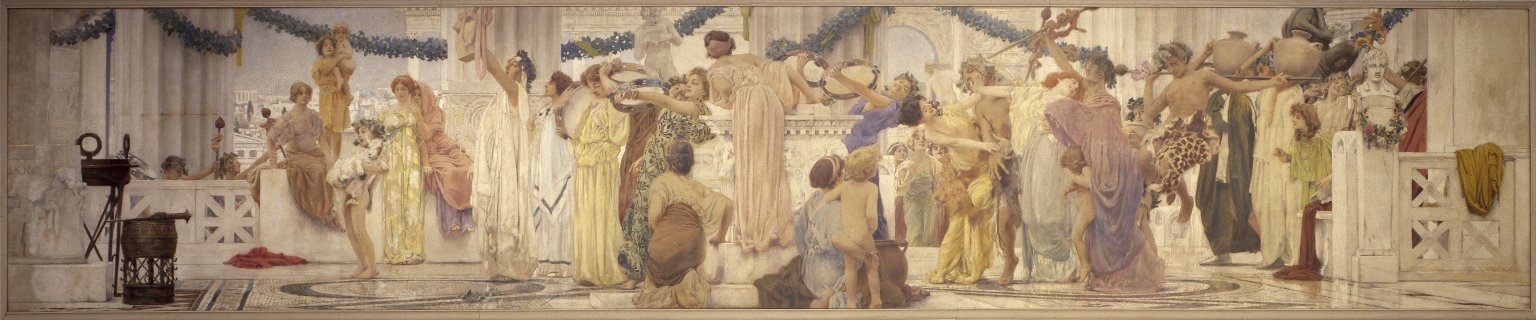

To begin with, who was Robert Frederick Blum and why is his work so important to this story? Blum began his professional career in 1879 as a pen and ink illustrator for Scribner’s Magazine in New York. During a trip to Europe in 1880, he visited his former teacher Frank Duveneck in Venice and met James McNeill Whistler. Working closely with Whistler, Blum began to experiment with pastel drawings. In 1882 Blum served as President of the Society of Painters in Pastel that he co-founded with fellow American artists William Merritt Chase, James Carroll Beckwith, and Edwin Blashfield, among others. At the height of his career, in 1890, Blum was sent to Japan by Scribner’s to illustrate a series of articles by Sir Edwin Arnold. He was among the first American artists to live in Japan between 1890 and 1893. The published illustrations from his experiences helped to promote interest in Japanese culture throughout the United States. Upon his return to the New York in 1893, Blum received praise and critical attention for the pastel drawings he exhibited and sold of Japanese subjects. That same year Blum was commissioned by Alfred Corning Clark, heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, to complete a series of murals for the new Mendelssohn Glee Club concert hall near Bryant Park. The Empire-style concert hall could seat more than 1,000 people and was adorned with gold finishes to embody the glamour of the Gilded Age. By 1898 Blum installed two large mural paintings, Mood to Music and Vintage Festival (each approximately 10 feet by 50 feet and including over 25 figures). The project established Blum’s reputation among the premier decorators of the American Renaissance at the turn of the twentieth century.

Emphasizing the seductive power of music without a clear narrative, the Mendelssohn Glee Club mural scheme demanded the viewer’s aesthetic imagination—moving beyond the skill of reading an image to a more intimate experience of appreciation. Attendance to the Mendelssohn Glee Club concert hall was by invitation only, but it is hard to imagine that the Hewitt sisters were not at the top of the guest list. Robert Blum’s aesthetic beliefs and remarkable talent as a draftsman were the talk of town in certain circles. He painted the Vintage Festival mural on canvas in his studio on Grove Street in Greenwich Village between 1895 and 1898. Unable to unroll the entire canvas at one time, he developed an elaborate process of transcribing ideas and figure studies through sequential series of individual drawings. This process was discussed by Royal Cortissoz in The Century Magazine as early as 1899. Today, for the first time it is possible to arrange the drawings to reveal the gradual developments Blum made through each iteration of the mural. [1]

Fig. 4. Robert Frederick Blum (1857–1903), Vintage Festival (Detail), mid-1895–1898; Mural panel painting; 292 x 1463 cm (114 15/16 x 576 in.); Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Edward Severin Clark, Frederick Ambrose Clark, Robert Sterling Clark, and Stephen Carlton Clark, 26.151

Fig. 5. Robert Frederick Blum (1857–1903), Vintage Festival, mid-1895–1898; Mural panel painting; 292 x 1463 cm (114 15/16 x 576 in.); Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Edward Severin Clark, Frederick Ambrose Clark, Robert Sterling Clark, and Stephen Carlton Clark, 26.151

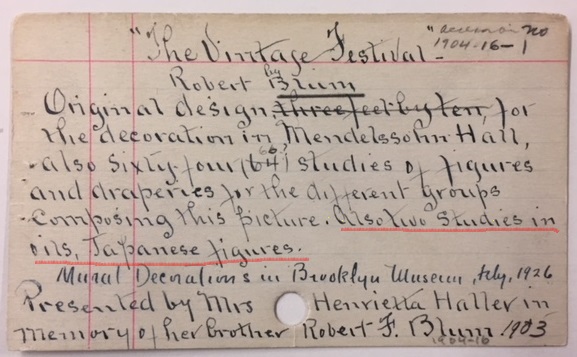

A cataloging card from the Cooper Union Museum lists the earliest description of the 1904 gift as: 64 preparatory studies for the Vintage Festival mural and “two studies in oils, Japanese figures” (Fig. 6). New research makes it possible to identify the studies in oil to be the Study for a seated woman pastel drawings (Figs. 1–2). The drawings are figure studies in preparation for the Vintage Festival mural, representing the intoxicating power of music, instead of Japanese women (Figs. 4–5). The confusion of the subject matter can be related to a note Eleanor Hewitt wrote in 1913 when the drawings were on display at the Hewitt home 9 Lexington Avenue (Fig. 7). Given the artist’s background, it is easy to understand a collector assigning a Japanese attribution without the comparison to the final mural. The Mendelssohn Glee Club murals were dismantled after the building was torn down in 1911. Blum was famous for his paintings of Japanese subjects and used multiple techniques in pastel that resemble the application of oil paint. Regardless of subject or media, one can imagine Eleanor and Sarah enjoying the beauty and graceful modulation of tones throughout the Study for a seated woman pastel drawings.

Fig. 6. Cataloguing Card, Department of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Photo © Smithsonian Institution

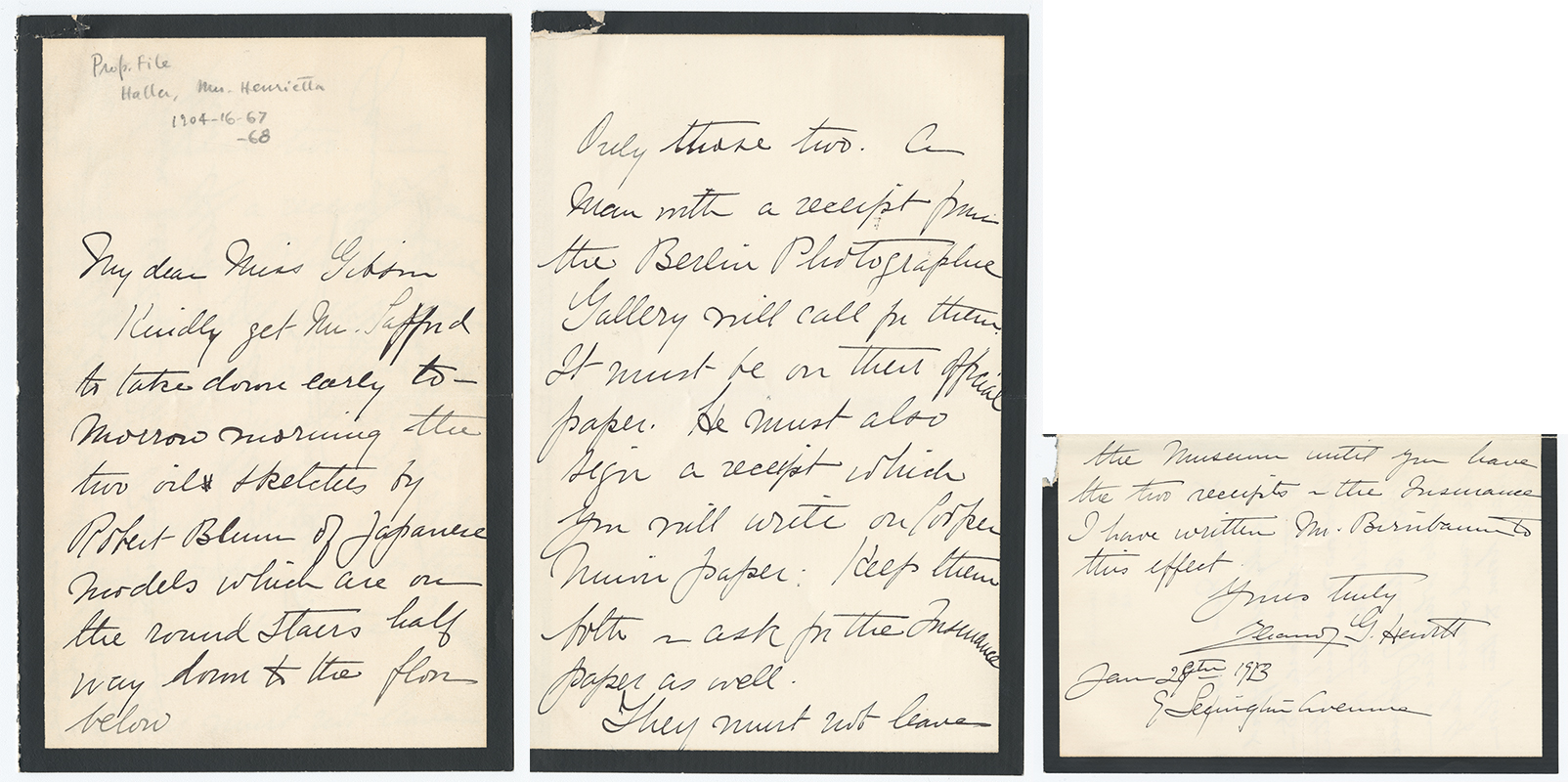

By 1913 the Study for a seated woman drawings were on display at 9 Lexington Avenue and integrated into the interior design of the Hewitt’s home. Eleanor’s note in response to art dealer Martin Birnbaum makes it possible to gain a glimpse of how the Hewitt sisters participated in the development of American art in New York during one of its most volatile periods. In February 1913 Birnbaum organized the first retrospective of Robert Blum’s work, a decade after the artist’s death, at the Berlin Photograph Company on Madison Avenue. Over 130 paintings, watercolors, pastels, and etchings were lent to the exhibition by thirty-eight institutions and private collectors, including two of Alfred Corning Clark’s sons and Eleanor Hewitt. On January 27, 1913 Birnbaum wrote Eleanor to thank her for lending “two studies in oil” for the memorial exhibition. He inquired about the titles and whether to credit “Miss Eleanor Hewitt” or the “Misses Hewitts” in the catalog. In response on January 29, 1913 Eleanor wrote a note to Miss Gibson to take down the two sketches by Robert Blum that hung “on the round stairs half way down to the floor below.” In the note Eleanor refers to the subject of the drawings as “Japanese models” and in the exhibition catalog the titles are listed as: “Two paintings of Japanese Women.” This description has remained in the cataloging files ever since.

Fig. 7. Registrar Property Files, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Photo © Smithsonian Institution

Displaying the Study for a seated woman pastel drawings at 9 Lexington Avenue allowed visitors to appreciate the talent of an American artist among the Hewitt’s European masterpieces. The decision to lend the drawings to the memorial exhibition was an act of support for building Blum’s legacy within the history of American art. The Memorial Loan Exhibition of The Works of Robert Frederick Blum opened days before the International Exhibition of Modern Art. Only a few blocks away at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue, the modern art exhibition (referred to as the Armory Show) was the first major installation of European modern art in New York. Many of Blum’s paintings and drawings were also on view for the first time; however, the memorial exhibition could not compete with the sensation that was sparked by the press when images of Marcel Duchamp’s paintings on display at the Armory Show were printed. In comparison, Blum’s work was dismissed by art critics as products from the last century instead of the modern era. In 1913 it is clear that for Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt, Blum’s drawings appealed more to their aesthetic taste and better served the didactic function of drawing for their museum than the bold and abrasive colors of modern art.

Dr. Josephine Rodgers is the Research Assistant for American Art in the Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design Department at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Footnotes

[1] Royal Cortissoz, “The Making of A Mural Decoration: Mr. Robert Blum’s Painting for the Mendelssohn Glee Club,” The Century Magazine (November 1899): 61.