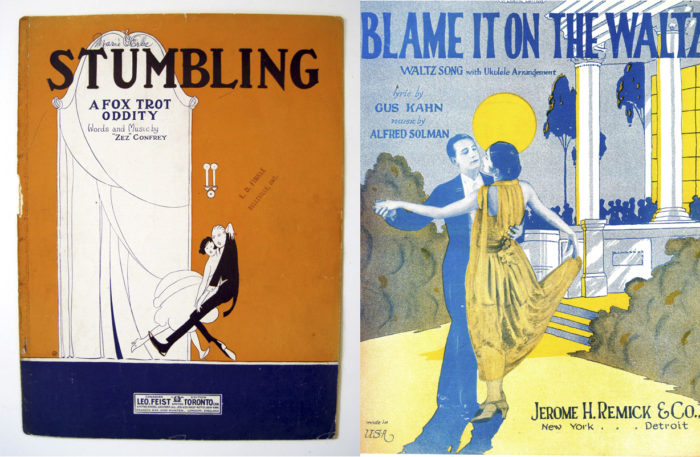

(L:) Sheet Music cover. Stumbling: a Fox-Trot Oddity. Confrey, Zez. New York: Leo Feist, Inc. 1922. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries. (R:) Sheet music cover. Blame it on the Waltz. Kahn, Gus, music by Alfred Solman. New York: Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1926. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

American jazz and popular dance tunes- for the foxtrot and other 1920’s and 30’s dances, dominated nightlife and entertainment in the movies and live performance.

The 1920s represented a period of “new wildness” and vibrancy created in the aftermath of the first World War in Europe and America. Coined the “Roaring Twenties,” the decade became popular for the rise of jazz and dance culture. With its origins in the United States, many of the dances were heavily influenced by the Harlem neighborhood’s timed dances and short, rhythmic beats, popularized by musicians and dancers in nightclubs in New York such as the Cotton Club and Savoy Ballroom. Prior dancing trends were based upon historical styles from before WW I such as traditional ballroom dancing- the one step, tango, as well as the dances popularized by the Ragtime genre.

Waltz: A derivative left over from previous ballroom styles of the early twentieth century, the waltz became intertwined with the Jazz Age through flowing footwork and dramatic facial expressions. This style of dance was characterized by small, double steps and the dance was fairly contained and restrained. Generally, it did not display the sense of swooping and the broad motion associated with modern, competition ballroom Waltz, or the high-speed, rapid rotation of the Viennese Waltz.

Fox Trot: The Fox Trot dance arose in the 1910s and was known as the “One Step.” With the advent of World War I, it was quickly forgotten but reappeared again in the 1920s as the “Fox Trot.” The foxtrot dance is known for its smoothness, characterized by long, continuous flowing movements across the dance floor. This dance is commonly accompanied with big band music and is stylistically similar to the Waltz, although the rhythm is in four-quarter instead of a three-quarter time signature.

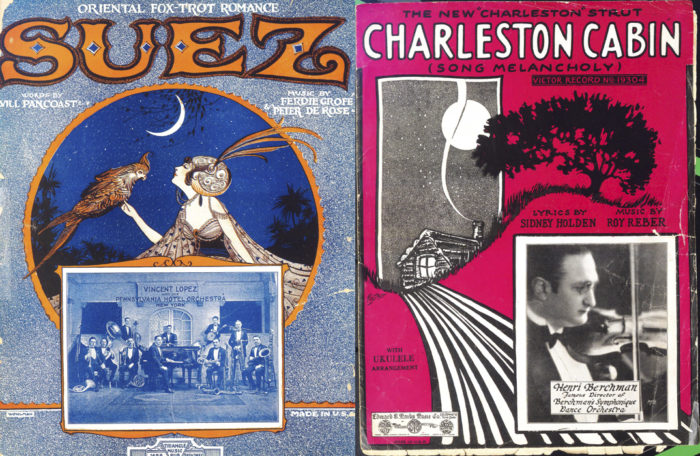

(L:) Sheet music cover. Suez; Oriental fox-trot romance. Ferde Grofé; Peter De Rose. Wohlman Studios, illustators. New York: Triangle Music Pub. Co. 1922. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

(R:) Sheet music cover. Charleston Cabin: (song melancholy). Reber, Roy and Sidney Holder. Irving Politzer, illustrator. New York: E.B.Marks Music Co. 1924 Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

The Charleston: This dance emerged in the 1920s when it accompanied James P. Johnson’s song “The Charleston” in the 1923 Broadway musical Runnin’ Wild. The variety of Charleston variations exploded with the advent of Charleston contests, for both solo dancers and couples across the world. Known for its complex footwork, the dance requires stepping backwards and then forwards, all the while kicking one’s legs out to the side. The second step is to move forwards and kick a front leg out, followed by moving backwards and kicking a leg back. The final step is to put both hands on both knees and move side-to-side by moving the knees apart and then together.

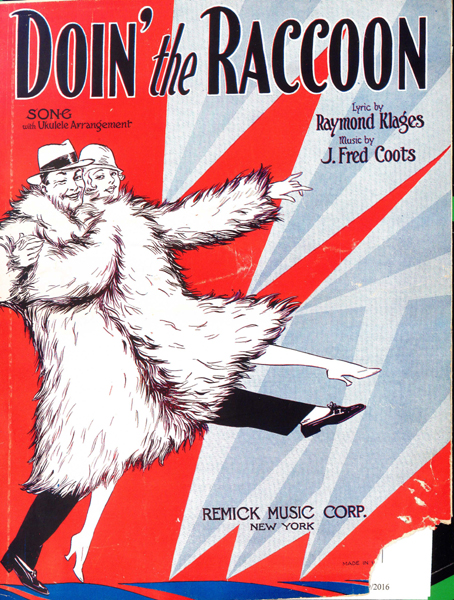

Sheet music cover. Doin’ the Raccoon. Coots, J. Fred and Raymond Klages. New York: Remick Music Corp. 1928. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

While ballroom dancing still resonated with older and more conservative men and women, the new dance crazes appealed to the younger generation who valued extreme sports, frivolity, and looser morals. In the period between the Wars, many young Americans were chastised by their elders for violations against decency, including using slang, performing “low-class” dances, and enjoying syncopated music with African American influences. During the Roaring Twenties young Americans responded to this criticism by broadening all of these “violations,” with more outrageous slang, jazzier music and dance, shorter and flimsier dresses and even shorter hair in reaction against these social rules of modesty and gender. There was no formal training for these new dances; the various steps, movements, and styles were informally “picked up” by party goers who would travel from one club to the next. It was, thus, in dance halls across the country in the 1920s that free form social dancing emerged.

This post was written by Elizabeth Broman and Sylvia Ferguson. Elizabeth is the Reference Librarian at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library. Sylvia Ferguson is a graduate student in the MA History of Design and Curatorial Studies program offered at Parsons The New School of Design jointly with Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.