The piano plays an intricate, rhythmic solo. The trumpet vocalizes a “wa-wa” sound that is explosively bluesy. The trombone whinnies bizarrely, both expressive and perverse. These are the sounds of Duke Ellington’s “Black and Tan Fantasy,” one of the defining musical pieces of his fifty-year career.

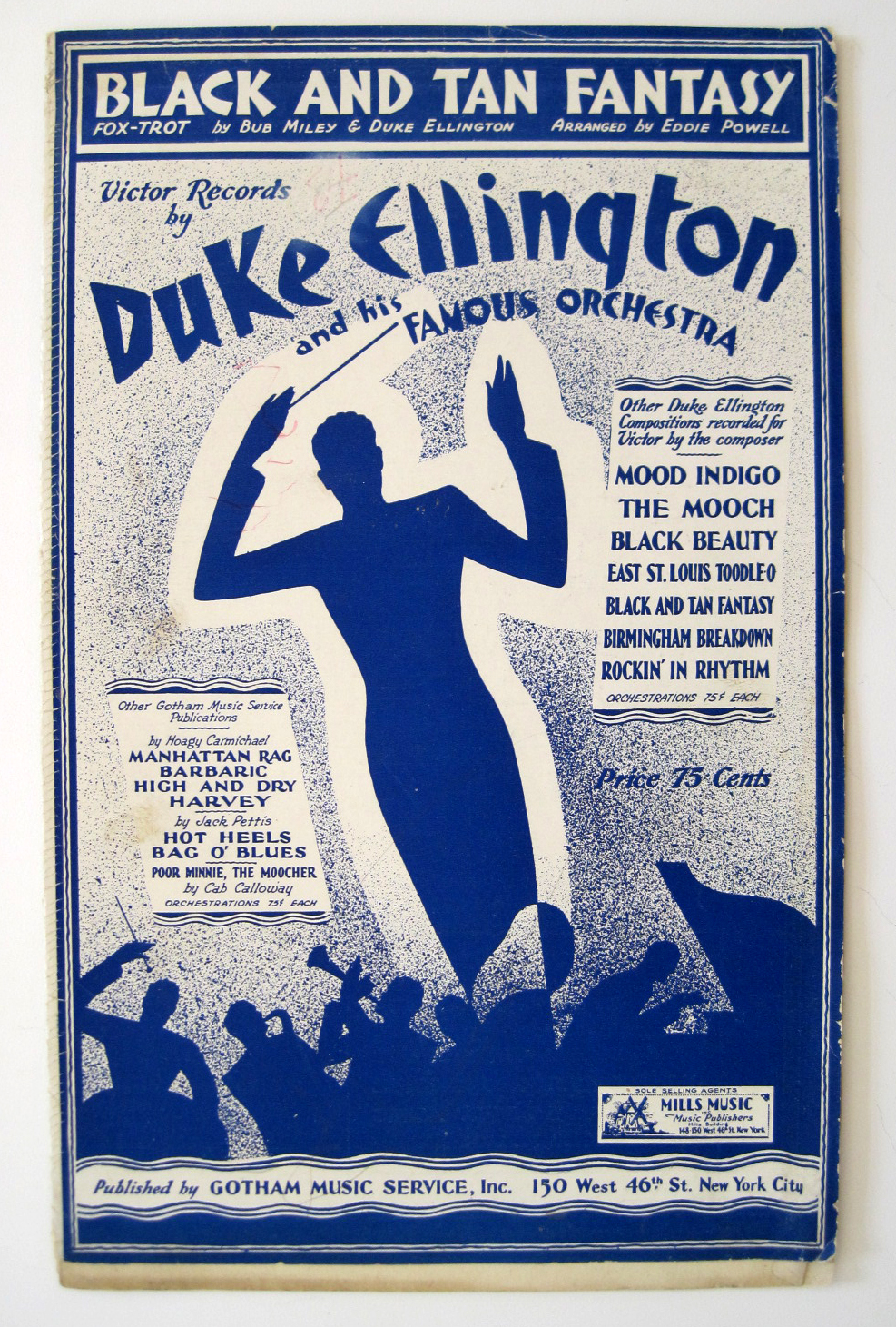

Sheet music cover. Black and Tan Fantasy. Arranged by Eddie Powell. By Bub Miley and Duke Ellington. Gotham Music Service, New York City, New York. 1927.

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899-1974) was involved with music from an early age. Both his parents were pianists, and Ellington began taking lessons at age seven. His mother emphasized the importance of refined manners and a dapper style of dressing, which earned her son the childhood nickname “Duke”—and it stuck. In 1917, his band “Duke’s Serenaders” was playing in Washington D.C. dancehalls for both African-American and white audiences. This multi-racial audience was rare, and it foreshadowed Ellington’s later, multi-ethnic popularity. In 1923, Ellington renamed the band “The Washingtonians” and moved to New York, where he switched from ragtime music to the dominant musical style of the Harlem Renaissance: jazz. He recruited James “Bubber” Miley, “Trick Sam” Nanton, Harry Carney and Johnny Hodges, some of the greatest jazz musicians of the time, to play in his jazz orchestra. He wrote music that matched each musician’s unique style, layering and blending the instruments’ textures. Their music had a diverse, individual and free-spirited sound perfect for swing dancing, the prominent dance style of the Jazz Age.

Ellington and his jazz orchestra are shown as silhouettes on the sheet music cover for “Black and Tan Fantasy.” Ellington plays the role of conductor, brandishing his baton before the band’s range of musicians and instruments. His leadership role is reflected by his prominence on the cover. The positioning also reflects Ellington’s method of composition; by composing music to fit his musicians, he directed the style and sound of the orchestra. The cover is part of The Cooper Hewitt Library collection, and is currently featured in The Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum’s exhibition, The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s.

Duke Ellington and Bub Miley co-wrote “Black and Tan Fantasy,” a musical arrangement meant for the foxtrot, in 1927. It features the wails, growls and moans of Miley’s trumpet—sounds that defined the group’s characteristic “jungle sound.” As the critic R.D. Darrell wrote, the music was “distorted and tortured, but agonizingly expressive…alien to all my notions of jazz.”[1] In the piece, their unique bluesy style is seen in tandem with components from spiritual songs and Chopin’s Funeral March, so the song “draws upon both black and white elements” and creates contrast and texture.[2] The song’s name itself suggests the type of interracial mingling seen in the music, and reflects the increased relaxation of racial attitudes that occurred in the Jazz Age.

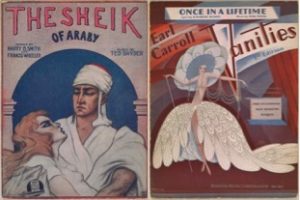

Alongside “Black and Tan Fantasy” in the Jazz Age exhibition there are two other sheet music covers: “The Sheik of Araby” and “Once in a Lifetime.”

L: Sheet music cover. The Sheik of Araby. Words by Harry B. Smith and Francis Wheeler. Music by Ted Snyder. Waterson, Berlin & Snyder Co., New York. 1921. R: Sheet music cover. Once in a Lifetime. Lyrics by Raymond Klages. Music by Jesse Greer. Robbins Music Corporation, New York. 1928.

“The Sheik of Araby” cover depicts a vaguely erotic scene with ‘The Sheik’ holding a young woman in his arms, who gazes at him longingly. “Once in a Lifetime” portrays a sensual woman; her dress evokes a peacock’s feathers and she seems to be mid-dance. In both illustrations there is an element of sexuality. Each cover also contains an element of the exotic, seen in the peacock feathers and turban-wearing Arabian man. This exoticism played a prominent role in Duke Ellington’s career.

In 1927, the same year “Black and Tan Fantasy” was released, Duke Ellington began leading the house band at the Cotton Club. The club was located in central Harlem, and was a prominent venue that displayed African-American performers to an entirely white clientele. The atmosphere was designed to be exotic for the white audience members. It evoked a savage jungle, with light-skinned dancers as the only non-African-American entertainment. Despite the racial stereotypes the club dramatized, the Cotton Club played a key role in the Harlem Renaissance by showcasing African American talent and giving Duke Ellington the space he needed to be a creative and inventive musical force. Ellington led the house band until 1930, and played sporadically there for another eight years. He also used their weekly radio broadcasts to extend his reputation and audience nation-wide. As Ellington’s following grew internationally and nationally throughout the years, the “Duke’s” charisma and inventive style was crucial to giving jazz the prominence and status of other, traditional music styles.

The Cotton Club and illustrations of the other two sheet music covers reflect the allure of the exotic. By examining the theme behind these covers, we can think further on how jazz music reflected the Jazz Age’s desire for a primal, sensual, outlandish experience. Through the growling trumpet and the free-spirited dancing Ellington’s music inspired, we see a type of liberation from the Puritan ideals that reigned before the 1920s.

Jessica Masinter is an intern in The Cooper Hewitt Library. She is a literary studies major at Middlebury College.

[1] Tucker, Mark, and Duke Ellington. A Landmark in Ellington Criticism: R. D. Darrell’s “Black Beauty” (1932). The Duke Ellington Reader. New York: Oxford UP, 1995. 57-65. Print.

[2] Metzer, David Joel. “Black and White: Quotations in Duke Ellington’s “Black and Tan Fantasy”.” Quotation and Cultural Meaning in Twentieth-century Music. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. 47-68. Print.