James Corbett Station—one of the first two public water stations—was deployed on March 7, 2001, at the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. A utility pole held brackets for the two dark blue flags—the color for water.

Responding to migrant deaths along the Arizona-Mexico border due to dehydration, minister Robin Hoover (along with former Navy engineer Tim Holt) designed a system for placing water in the desert. Their project, Humane Borders Water Stations and Warning Posters, is featured in the exhibition By the People: Designing a Better America, curated by Cynthia Smith, Curator of Socially Responsible Design at Cooper Hewitt.

Cynthia Smith (CS): You had been working on issues of transnational migration before founding Humane Borders. What circumstances led you to create the humanitarian organization?

Robin Hoover (RH): In 1986, I began working in the migration policy space as a Sanctuary Movement volunteer in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Completing my PhD in Political Science in the 1990s, researching the politics of faith-based groups working on migration. Then in January of 2000, after a national search, I became the pastor of the First Christian Church in Tucson, Arizona. In June 2000 some eighty persons gathered in the Pima Friends Meeting House (Society of Friends) and decided to found an organization with a twofold mission to (1) respond with humanitarian assistance for the migrants who were risking their lives crossing the US–Mexico border and (2) advocate for changes in US policies that were placing the migrants’ lives in peril.

CS: Humane Borders works with thousands of volunteers from around the world, many through their churches. Historically, why are faith-based groups in the US important actors in addressing social justice issues?

RH: Every major social movement and every significant human-service delivery system in the US was first articulated and demonstrated in the faith communities of the US. These even include the anti war movement, gay rights, civil rights, and more. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was first a church leader. The cross was in front of every march led by Caesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Mental health, hospitals, education, life insurance, guild groups, cemetery associations. The whole nonprofit sector of the US economy owes its existence to the voluntary associations that Alexis de Tocqueville noted in 1835.

CS: How did the concept for the first water station come about? Where were the first public stations deployed? What did you learn and improve with each iteration?

RH: It was very easy to connect the idea of providing water in the desert for migrants to the biblical witness of hospitality. It was easy to link that to the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Giving a cup of water in Christ’s name has a long theological and practice history. We knew we needed to put water in the desert, but we were unsure how. We envisioned stations and began thinking about barrels, sanitation, identification, permission, strategic locations, maintenance, safety, environmental constraints (animals, insects), sunlight, and chlorination. We began talking to land managers. They wanted to meet all the same requirements as we did. The very first station was deployed along the railroad line from Nogales, Mexico, to Tucson, Arizona. This station was perhaps seventy-five feet to the side so as to be out of the right-of-way. All through Arizona, migrants follow fences, utility lines, railroads, roads, pipelines, and other features on land.

All of the stations for years were one specific color of blue. We simply standardized the paint for cost reasons. Touch-ups would match, that sort of thing. The stations needed to look clean and well cared for. The barrels needed to be opaque enough that we would not experience any algae blooms in the water. The paint accomplished that. Blue is one of the—if not the—most unusual color in Arizona, and it is a symbol for water. We wanted the stations to be conspicuous, standard, recognizable, located in logical, strategic places, and to be used in a way that would help accomplish the goals and mission of the land managers. No one wanted the desert to be damaged by our equipment, our presence, or the presence of the migrants.

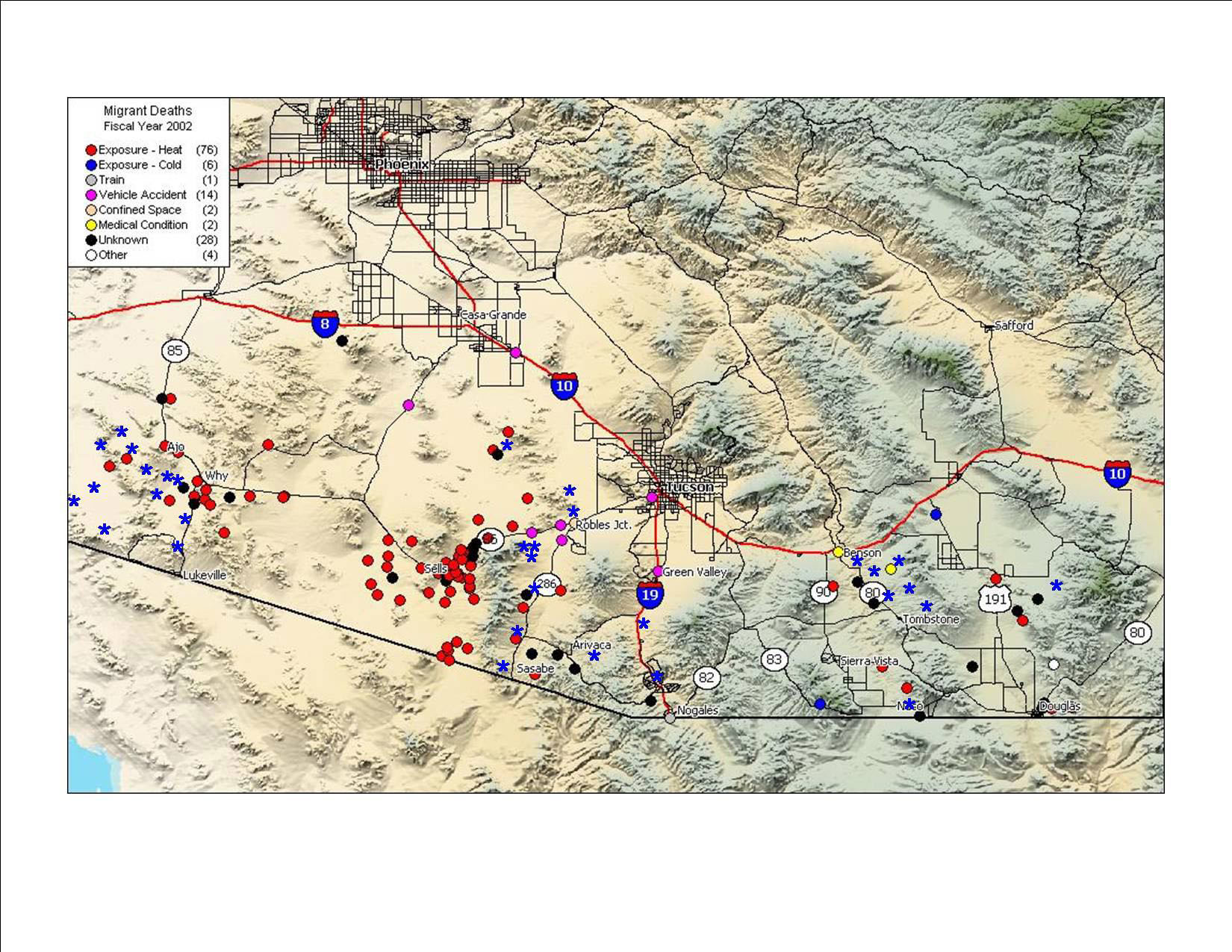

An early (2002) mortality map of the Arizona border with Mexico. Based on the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner data, red dots identify locations where migrants were dying, which helped Humane Borders make strategic decisions about where to collaborate with landowners and managers about water- station placement.

In 2002, Hoover and volunteers were in the process of deploying a station in Robles Junction, Arizona: “We set the stand, started filling the barrel, raised the flag, and this little guy ran out of the bush. ‘They told me to look for the blue flag to get water.’ He got a gallonful and disappeared before we filled it up.”

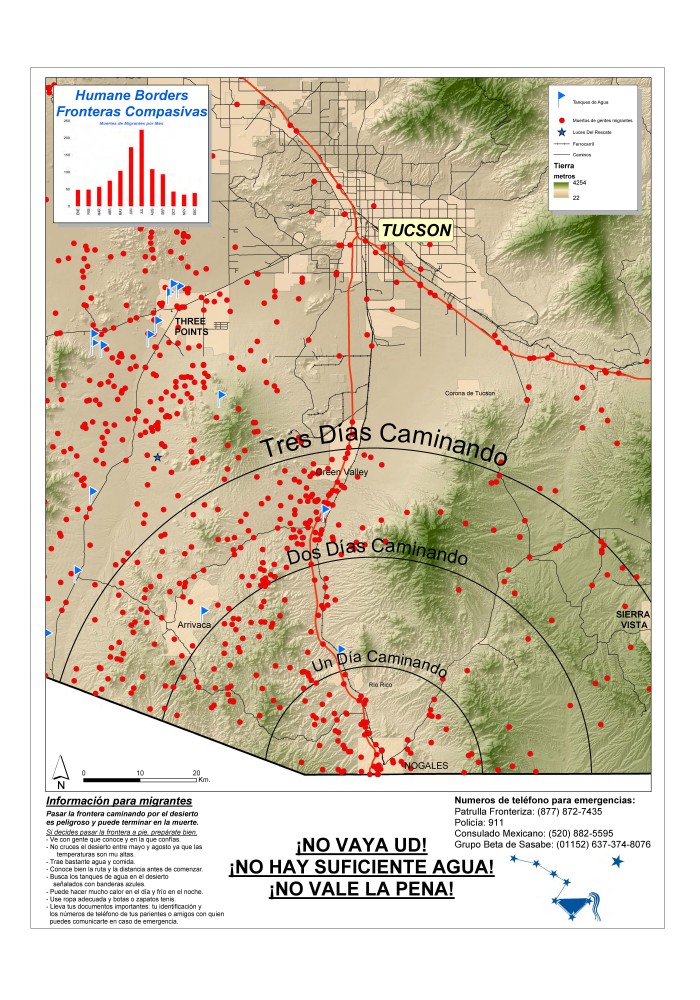

Humane Borders Nogales Warning Poster (2013).

CS: Why was it important to include a flag thirty feet in the air with each station?

RH: At the beginning of our work, migrants most often walked in the most convenient areas, which meant that they walked in the middle of the valleys. There are twelve valleys that connect Mexico to Arizona. One can see something like a thirty foot flag for a great distance.

CS: When and how did Humane Borders begin tallying migrant deaths in the Sonora Desert? Why is the use of data important? How did this help determine where to place stations?

RH: Migrant death tallies began when the Pima County Forensic Science Center (Office of the Medical Examiner) began separating out the suspected migrant deaths from their death counts. As these were public records, the local papers would report the deaths. The Border Patrol’s Community Relations guy brought me a topo map with some of the deaths plotted in the fall of 2000. I purchased an Arizona topo map computer program and began obtaining the GPS locations of the deaths. These were plotted. We began using a red dot for the death symbol. We showed the surface management responsibility projections on the maps so that we could talk to land managers about where the deaths were located. Since the Border Patrol only finds some seventy to seventy-five percent of the migrant remains in a given year, we would also obtain the locations from the ME’s office of where the deceased migrants or remains were recovered. Kim Johnson and I would spend hours plotting and printing the maps with locations. We established some of the parameters of accuracy that would be used later. Very soon, we had the only and best projections of where the migrants were dying. Media were immediately attracted to them. The death locations told us who we needed to be working with, where the stations needed to be deployed, and they were a surrogate measure of where the migrants were walking.

Early in 2005, I came up with the poster-size warning poster idea. Something with more detail for a migrant to study before crossing into the United States or perhaps to understand he was crossing in the wrong month. We came up with a topo projection that included city and road elements. The signage was a warning. It included a graph showing the most dangerous, deadly months, distances, etc. It also included advice to the person who chooses to continue anyway. We began distributing these in border towns in Sonora in May of 2005.

CS: Around the globe, people are fleeing areas of conflict and being displaced due to climate activity. What can each of us, and especially designers, learn from your years of experience that might improve conditions for migrating populations?

RH: Migration is a basic human right. It is ensconced in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is well grounded in the Catholic Social Teachings. It is recognized by many nations and traditions. We’ve moved far from the concept of latifundia, wherein the people belong to the land. They don’t even belong to nations. They’re free agents. Along the border, we’ve learned that all borders are porous. People will migrate for money, family, security, relief, futures. There are millions of people who want to help others in distress. It’s part of their traditions, their polities, their political visions, their worldviews. Facilitating the movement of a highly motivated person in distress is a basic act of kindness and compassion.

One of the busiest, the Little Ranch seasonal station is deployed only from April through October. Located on Ironwood Forest National Monument land, under an annually renewed permit from the US Bureau of Land Management.

This interview is excerpted from the exhibition publication By the People: Designing a Better America.