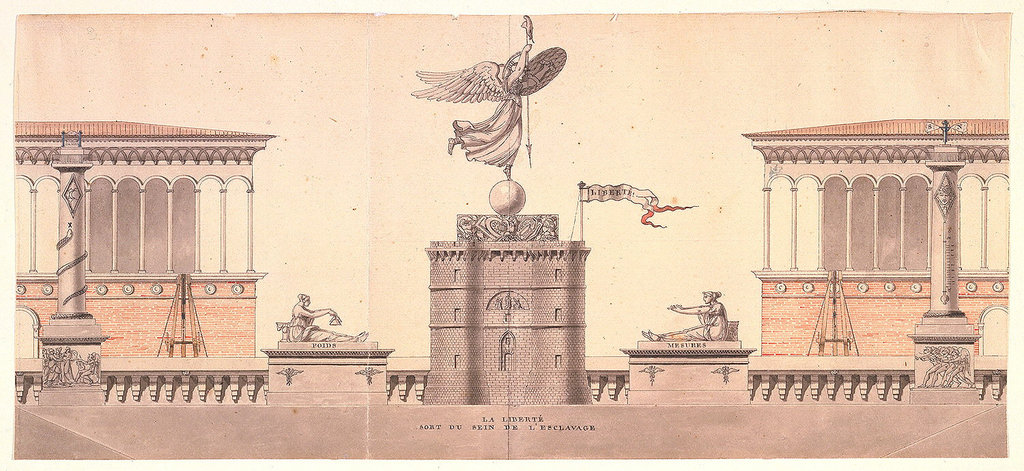

The infamous Bastille prison was demolished in 1789, in the first year of the French Revolution, an event that had great political as well as artistic consequences. This pen and wash drawing is a design for a monument intended for the Place de la Bastille following the destruction of the prison. The design has been loosely attributed to the eclectic French architect Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757- 1825, also spelled Lequeue). However the lack of marginalia and the execution of the drawing is a departure from Lequeu’s drawings and this unsigned drawing is likely designed by an anonymous member in the unofficial grouping of architects designated in contemporary scholarship as “revolutionary architects,”—a list that includes designers such as Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.

Architects during this period produced a large number of potential monuments to replace the old symbols of the monarchy. This particular design commemorates the systematization of weights and measures in France. On May 8, 1790, the Assemblée Nationale of the nascent French Republic tasked the Academy of Science with the creation of a system of weights and measures based on universally accepted units taken from nature. Five year later, on April 7, 1795, the Assemblée moved to officially adopt the mètre (meter), giving rise to the modern day metric system.

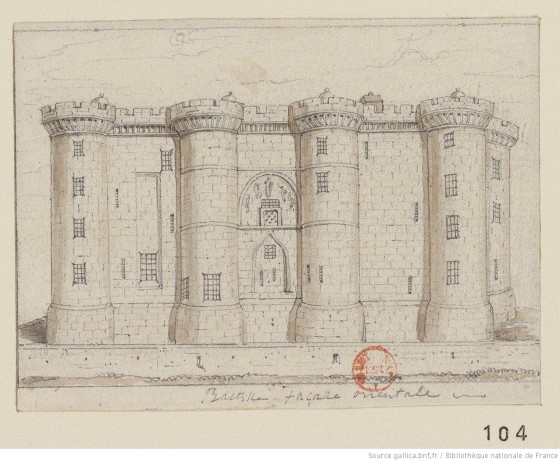

The monument can be compositionally divided into three parts. In the forefront is a row of five monuments, behind that a balustrade, followed by two cranes with two Tuscan loggias in the far background. The central monument is a combination of a pedestal in the shape of the eastern façade of the Bastille prison, which flies a small tricolor printed with “liberté.” Mounted on top is the personification of Liberty, imagined as a cross between Minerva with her crested helmet, shield and spear, and Nike, the winged goddess of victory. This central monument is flanked on either side by the personification of weight (poids) and measurement (mesures), both depicted as classical female statues with accoutrements of their respective allegories. They rest on classical plinths that are marked with a caduceus, a symbol related to the god Mercury and employed since the Middle Ages as a symbol of diplomacy. At the far ends in this front row of monuments are designs for columns. On the left, a serpent wraps around a column that is marked with the Roman numeral for ten and a symbol of a moon. This particular column can be interpreted as a reference to the new French Republican calendar in which the months were divided not into weeks but in increments of ten days. The right column is transformed into a giant thermometer, perhaps alluding to the adoption of the decimal system in angular measurements. In the lower register is the following inscription: “La liberté sort du seine de l’esclavage” (Liberty emerged from the bosom of slavery), once more stressing the baseline of the French Revolution.

Drawing, Eastern Façade of the Bastille Prison, 1790-91; Anonymous, Graphite with brown wash on paper, 7.5 x 10.2 cm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie Paris, Inv. No. RESERVE FOL-VE-53 (C)

This type of architecture is often referred to as “architecture parlante”, or speaking architecture in which the ornament and the form unveils the function of a given building. This monument extends beyond a commemoration of a measurement standard and is in fact a celebration of the ideals of liberty and the Enlightenment desire for rationalism. In fact, the standardization of measurements was part of the on-going desire to clear away the old regime’s confusion of laws, codes, and fiscal organizations. The lack of set standards of measurement and weight, prior to the 1790s, encouraged various regional variants which enabled feudalistic governing to continue unchecked. As such, a frequent demand in the cahiers de dolénces (statements of grievances) in 1788-9 was the unification of weights and measures and the slogan “un roi, une loi, un poids, et une mesure” (one king, one law, one weight, and one measure) became a rallying cry in the quest for equality.

The monument itself was not actually realized as this was a period that of instability both socially and financially. Rather, the format of the drawing can be tied to the Prix de Rome, a competition in which students in the Royal Academy of Architecture invented monuments based on given topics and parameters for a chance to study in Rome. In this monument, the subversion of proportions, disregard for architectural order and the emphasis on oversized statuary directly challenges traditional academic standards. When the typology of the drawing is considered together with its subject matter, the drawing can be considered as a celebration of political and artistic freedom, the ideals of the revolution distilled into a design for a paper monument.

To this day, there are still tangible residues from this adoption of the metric system at the end of the eighteenth-century. At 36 rue de Vaugirard in the sixth arrondissement in Paris, a mètre étalon from the eighteenth-century is embedded in the exterior of the building!

Cabelle Ahn is a graduate intern in the Department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She received her MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art and is currently studying eighteenth century decorative arts at the Bard Graduate Center.

One thought on “For Liberty, Equality, and the Metric System”

Bill Bahr on January 16, 2017 at 5:20 pm

Thanks! Very interesting. You might be interested to know of my recent research into the correct dimensions of the Bastille, which involved finding three original drawings from an engineer, a construction contractor, and an architect all made before the destruction of the Bastille. Extended scales needed to be constructed via photo-shopping and conversions needed to be made from toises and pieds du roi into feet and meters. Ref: “George Washington’s Liberty Key: Mount Vernon’s Bastille Key” pp 29-30 or for a more accessible and extensive discussion: http://www.bahrnoproducts.com/Extra_Supplements.htm

Good luck in your studies!