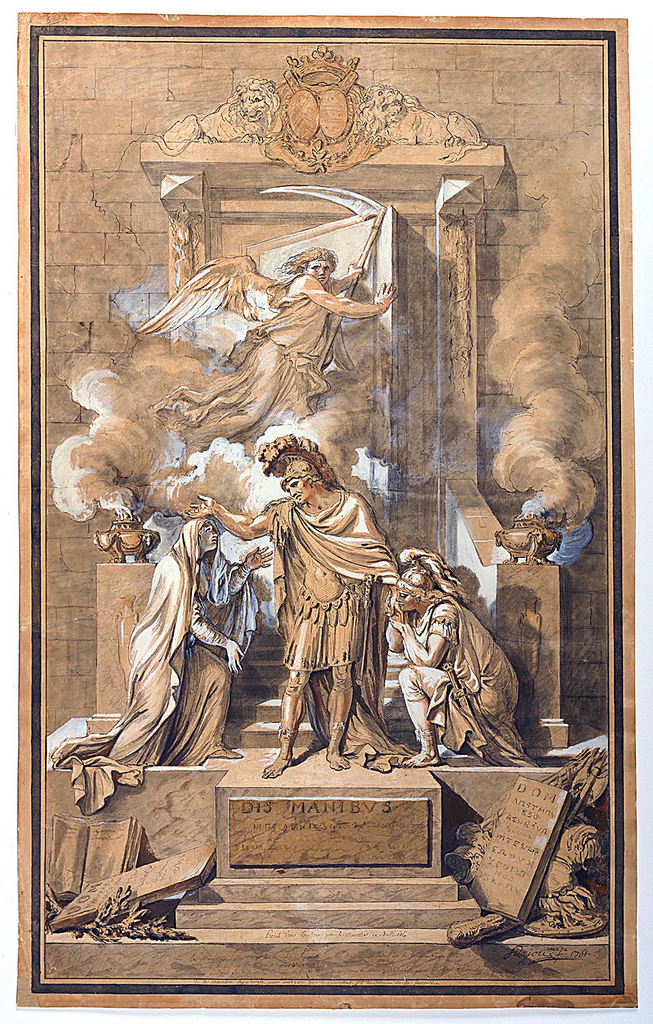

This highly finished drawing is a design for a tomb by the French academician and sculptor Augustin Pajou (1730-1809). Dated to 1761, the drawing is executed with pen and wash and heightened with white gouache, and is signed and dated by the artist in the lower right corner. This tomb design is an innovative composition that presents a novel outlook on death and the afterlife in eighteenth-century France.

The tomb was designed for Charles-Louis-Auguste Fouquet ( 1684 – 1761), Maréchal de Belle-Isle. The Maréchal was the grandson of Nicolas Fouquet, Louis XIV’s ill-fated Superintendent of Finance, now remembered as the creator of the opulent Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte. Unlike Fouquet, the Maréchal enjoyed an illustrious military and political career under Louis XV, serving as commander-in-chief of the French troops in the Bohemian campaign (1741-43) and ultimately serving as the Secretary of War. The writer and philosopher Voltaire especially admired Belle-Isle’s abilities as a commander and as a statesman, and incorporated Maréchal’s dispatches in writing his Histoire de la guerre de 1741.

In Pajou’s design, the Maréchal , dressed in neoclassical armor, stands on a platform up a flight of stairs. His wife receives him to the left and his son, the Comte de Gisors, kneels to the right—their poses inspired by baroque catafalques. While the Maréchal’s wife wears a shroud, the Comte de Gisors is dressed all’antica. Both predeceased Belle-Isle and the two figures replace the Christian allegorical figures that would normally be in their places according to conventions of tomb design. In the background, the angel of death holds a scythe and closes the door to the sepulchral chamber to indicate that the Maréchal is the last of his line to die. In the lower right, the club of Hercules, Roman cuirass and martial trophies emphasize the military heritage of the family, while the open book and the olive branch in the left foreground symbolize peace that follows war. Smoking braziers in the foreground give the tomb a pictorial atmosphere. The central tablet reads “Dis Manibus” (To the Spirits of the Dead/Departed) and the tablet to the side reads, “Dom : deo optimo maximo”(To god the greatest good). In the lower register, the text can be translated as, “Project for a Tomb for the Maréchal de Belle Isle/ Allegory, the Maréchale enters a sepulchral chamber where the tombs of his wife and his son, the Comte de Gisors are. Both dead before him.” The captions and the composition together reveals that Pajou has created an imaginary architectural space not privy to the living—a glimpse inside the sepulchral chamber for the dead spirits.

This tomb was not realized due to the debts in the Marechal’s estate. Pajou likely designed this tomb on speculation and in fact, the arms at the top of the drawing are not those of Belle-Isle. Pajou exhibited this drawing at the Salon of 1765, where the art critic and connoisseur, Denis Diderot was dismissive, writing “M. Pajou, Give it a sepulchral and lugubrious air if you want me to say something good about it.” Diderot’s criticism can be attributed to Pajou’s audacious conception of the underworld and his bold composition that takes the tragic extinction of a family line as its main theme. Pajou’s design negotiates traditional visual imagery with innovative narratives and appears at a transitional moment when Enlightenment ideals influenced representations of death and the afterlife.

Cabelle Ahn is a graduate intern in the Department of Drawings, Prints and Graphic Design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She received her MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art and is currently studying eighteenth century decorative arts at the Bard Graduate Center.